calsfoundation@cals.org

Hartford (Sebastian County)

| Latitude and Longitude: | 35°01’22″N 094°22’53″W |

| Elevation: | 653 feet |

| Area: | 1.88 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 499 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | March 5, 1900 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

460 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

1,780 |

2,067 |

1,210 |

1,189 |

865 |

531 |

616 |

613 |

721 |

772 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

642 |

499 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The city of Hartford, in southern Sebastian County, is most famous for its role in the history of gospel music publishing. A city that flourished during the peak of coal mining in western Arkansas early in the twentieth century, Hartford has diminished in population but remains an anchor of the region.

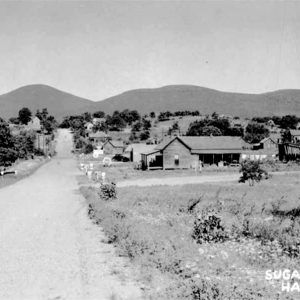

The history of Hartford is actually an account of two communities. The older settlement to take the name Hartford dates to before the Civil War. About seventeen families were homesteading in southern Sebastian County, between the Sugar Loaf and Poteau mountains. Their settlement was known to some residents as the Old Sugarloaf Valley Community, but most called the settlement Hart’s Ford, honoring Betsy Hart, the widow of James Hart, who lived near the crossing of West Creek. A post office was established in Hartford in 1874. By 1891, the community included a union church (shared by Methodists, Cumberland Presbyterians, and Baptists), a public school, and a store. Meanwhile, a second settlement a few miles away developed after the Civil War. Sometimes called Center Point, it later took the name Gwyn from landowner Wylie P. Gwyn (or Gwynn), who began homesteading in a log cabin in 1868 and who began mining coal on his property sometime in the 1880s. Late in that decade, the Choctaw-Memphis Railroad Company bought a right-of-way near Gwyn. In 1899, the railroad purchased additional land that was known to contain coal deposits. The company was later acquired by the Rock Island Railroad.

The new community that grew up along the railroad was variously called Gwyn and New Hartford, while the older settlement was known as both Old Hartford and West Hartford. The newer community was incorporated early in 1900. By 1905, it was using the name Hartford. The population increased rapidly, due to coal mining, and four banks were established in the city. Most of the miners were of European origin, causing one part of the growing city to be labeled Little Italy, although Germans, Poles, and Greeks were also included in the population. The city is estimated to have had roughly 4,000 residents in its peak years between 1910 and 1920. Hartford had eight doctors, a hospital, two dentists, several lawyers, three livery stables, three drugstores, several restaurants and saloons, two hotels, two movie theaters, and nine churches (Apostolic, Episcopal, Baptist, Christian, Roman Catholic, Methodist, Presbyterian, Assembly of God, and Pentecostal). An eight-room brick building was completed in 1910, providing all twelve grades of the public school. Sixteen coal mines operated within seven miles of Hartford, including three within the city limits. The business district was twice damaged by fire, but both times businesses quickly rebuilt.

Many of the coal miners in Hartford joined the Knights of Labor, which later became part of the United Mine Workers labor union. When the Prairie Creek Coal Mining Company attempted to operate one of its mines as a non-union operation in 1914, the miners went on strike, and the strike included so much violence that federal soldiers were called in to protect the property. Miners succeeded in keeping the mining companies from operating non-union mines in the Hartford area.

During these peak years, Hartford also became a center for publishing gospel music. Will Ramsey and David Moore owned a store in Hartford that sold musical instruments, phonographs, and sheet music. Eugene Monroe (E. M.) Bartlett persuaded Moore to become a partner with him in the Hartford Music Company, which by 1931 was printing and distributing more than 100,000 books of music a year. The company was purchased by Albert Brumley and moved to Missouri in 1948.

The population of Hartford declined rapidly as coal gave way to oil/gas as a means to fuel industry and transportation. In spite of the decline of the city, the school continued to grow, thanks to consolidation of smaller school districts of the county, including Unity, West Hartford, Center Point, Midland, and Prairie Creek. An additional frame building was added to the school district in 1925, and a high school building was erected in 1930. During the Depression, the Public Works Administration (PWA) built a water tower in Hartford that was completed in 1936.

The Hartford School District continued to serve southern Sebastian County through 2018. The district claimed that Hartford High School was the first high school in Arkansas with a lighted football field. The district was consolidated with Hackett (Sebastian County) in 2015 and ceased operations completely in 2018.

The business district of Hartford was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2009, joining the PWA water tower. The Methodist church building, constructed in 1921, was added to the register in 2011.

The Scott-Sebastian Regional Library System, headquartered in Greenwood (Sebastian County), provides public library service to five branches in two counties, including a branch in Hartford.

For additional information:

Bowden, Bill. “Heart of Hartford: Town Faces Its Last Year With A School.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 28, 2018, pp. 1A, 7A.

Cardin, Alberta. “They Came to Hartford.” The Key 2 (Spring 1967): 22–23.

“Hartford: Its Days of Glory.” The Key 1 (Spring 1966): 12–13.

Michael, Norma Lockhart. “Hartford—Past and Future.” The Key 10 (Spring 1975): 23–25.

Moore, Jerry H., and Lonnie C. Roach. No Smoke, No Soot, No Clinkers. N.p.: Frank Boyd, 1974.

Steven Teske

Butler Center for Arkansas Studies

Hartford Cemetery

Hartford Cemetery  Hartford Church

Hartford Church  Hartford Coal Mining

Hartford Coal Mining  Hartford Commercial Historic District

Hartford Commercial Historic District  Hartford Commercial Historic District

Hartford Commercial Historic District  Hartford Commercial Historic District

Hartford Commercial Historic District  Hartford Music Company and Hartford Music Institute

Hartford Music Company and Hartford Music Institute  Hartford Street Scene

Hartford Street Scene  Hartford Water Tower

Hartford Water Tower  Sebastian County Map

Sebastian County Map  Sugar Loaf Mountain

Sugar Loaf Mountain

My grandfather, Benjamin McKinney, was part owner of a small coal mine in Hartford, Arkansas. He was killed when there was an explosion in the mine sometime around 1929 or 1930. Benjamin McKinney’s name can be found on the Coal Miners’ Memorial in Greenwood, Arkansas. The McKinney names on that memorial are all relatives of my grandfather. My mother was only four years old when he was killed, and her brother was born after Benjamin McKinney died. We have very little in the way of information about him. After his death, my grandmother ran a gas station on Highway 71 in Greenwood.