calsfoundation@cals.org

One-Drop Rule

aka: Act 320 of 1911

aka: House Bill 79 of 1911

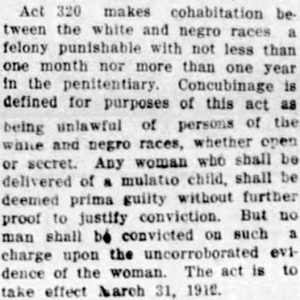

In 1911, Arkansas passed Act 320 (House Bill 79), also known as the “one-drop rule.” This law had two goals: it made interracial “cohabitation” a felony, and it defined as “Negro” anyone “who has…any negro blood whatever,” thus relegating to second-class citizenship anyone accused of having any African ancestry. Although the law had features unique to Arkansas, it largely reflected nationwide trends.

Laws against interracial sex were not new. Virginia declared extramarital sex a crime during Oliver Cromwell’s era and increased the penalty for sex across the color line in 1662. In 1691, Virginia criminalized matrimony when celebrated by an interracial couple. Maryland did so the following year, and others followed. By 1776, twelve of the thirteen colonies that declared independence forbade intermarriage.

Though the intermarriage ban widened, extramarital interracial sex—at least between white men and Black women—was tolerated. By 1910, twenty-nine of the forty-six states, including Arkansas, prosecuted intermarriage but not such instances of interracial sex. Public rhetoric justified such laws as preserving “racial purity.” Nevertheless, tolerance of white male/Black female liaisons versus punishment of Black male/white female relationships showed this to be a rationalization. Scholars suggest that marriage was punished because it implied social equality—an alliance between families that was not tolerated across the color line. Mere sex lacked such implication.

Until Reconstruction, states found ways to accommodate interracial families. However, tolerance faded during the Jim Crow era. House Bill 79 outlawed interracial families altogether, declaring the mere existence of a biracial child evidence of parental crime.

The law also defined “Negro” as having “any negro blood whatever.” Dichotomous “racial” classification was also invented in colonial times, with blood-fraction laws defining a “Negro” as having more than a given fraction of African ancestry. North America’s first blood-fraction law, in 1705, used a one-eighth rule (a person was Black if one great-grandparent was entirely of African ancestry). By 1910, twenty states classified citizens by blood-fraction, most using one-fourth or one-eighth. However, appearance also played a role in racial definition in pre-1911 Arkansas, as exemplified by the case of the 1861 freedom case of Guy v. Daniel, in which slave Abby Guy was awarded her freedom largely because of her appearance and behavior. Before 1911, Arkansas’s railroad segregation law defined “Negro” as “one in whom there is a visible and distinct admixture of African blood.” However, the emergence of scientific racism gave rise to the notion that a person could look and self-identify as white but still somehow be Black.

A neighboring state outlawed interracial sex three years earlier. Louisiana’s Act 87 of 1908 declared “concubinage between a person of the Caucasian or white race and a person of the negro or black race” a felony. The law was tested in 1910 when the Louisiana Supreme Court overturned the conviction of Octave Treadaway of New Orleans and his mistress. Chief Justice Provosty ruled that the woman was neither “Negro” nor “Black”; rather, she was “Coloured,” an intermediate caste based upon dual ancestry, as defined in Louisiana caselaw. Within a month of Provosty’s ruling, lawmakers reconvened, amending the statute to define “Negro” via a one-thirty-second blood fraction—in effect, a one-drop rule.

When Arkansas’s legislature met the following year, it left no wiggle-room for a recalcitrant judge. They adopted the wording of Louisiana’s statute while adding the one-drop clause. The felony for interracial sex was “punishable by one month to one year in penitentiary at hard labor.”

House Bill 79 was introduced in the Arkansas General Assembly on January 16, 1911, by Representative Napoleon B. Kersh of Lincoln County. According to the next day’s Arkansas Gazette, an amendment was offered that would limit the bill’s provisions only to Lincoln County, but the amendment was defeated. The bill was read in the state Senate on February 3 and was referred to committee, where it waited until the special session called by Governor George Washington Donaghey to deal with other unfinished legislative business. The bill was quietly approved on May 30, with little notice or fanfare.

Oddly, the first case appealed to the Arkansas Supreme Court based on the 1911 statute was a dispute over school segregation, not sex. In 1921, three great-grandchildren of Maria Gocio, who were by all physical appearances white, were expelled from Public School 16 in Montgomery County because Maria admitted to a trace of Cherokee ancestry. The school felt that Cherokee had “Negro” blood. The children’s parents sought a mandamus order based on the railroad-segregation law (“visible and distinct admixture”). They lost in State v. School District (1922) when Arkansas Supreme Court Justice T. H. Humphreys ruled that the 1911 law applied (“any trace of negro blood”). The children and their future descendants were ruled to be Black because of a great-grandmother’s Cherokee ancestry.

The language of Act 320 continued to be published in the statutes of Arkansas through the 1960s, although repeal of various laws demanding separation of whites and African Americans (and a general failure to enforce laws forbidding extramarital sexual relations) made its provisions obsolete. Act 320 essentially disappeared from the books with the passage of Act 280 of 1975, which rewrote the criminal code of Arkansas’s statutes, no longer addressing extramarital sex and no longer defining race in terms of ancestry.

For additional information:

Murray, Pauli, ed. States’ Laws on Race and Color. Athens: University of Georgia, 1997.

Sweet, Frank W. Legal History of the Color Line: The Rise and Triumph of the One-Drop Rule. Palm Coast, FL: Backintyme, 2005.

Frank W. Sweet

Backintyme Publishing

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Act 320

Act 320

This was a bona fide lie. You are 50% of your mom’s DNA and 50% of your dad’s DNA, therefore, you CAN’T DENY ONE.