calsfoundation@cals.org

Agricultural Adjustment Act

The experimental Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) was the cornerstone farm legislation of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal agenda and was steered through the U.S. Senate by Joe T. Robinson, Arkansas’s senior senator. In Arkansas, farm landowners reaped subsidy benefits from the measure through decreased cotton production. Arkansas sharecroppers and tenant farmers did not fare as well, bringing about the establishment of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union (STFU).

Upon taking office in 1933—during the fourth year of the Great Depression, on the heels of the Drought of 1930–1931, and amid the full force of the Dust Bowl—Roosevelt promised “a new deal for the American people” centered on “relief, recovery, and reform.” Counseled by advisors dubbed the “brain trust,” Roosevelt fashioned a farm leaders’ conference drawing on Henry A. Wallace, Rexford G. Tugwell, and George N. Peek. Utilizing their best proposals, he brought about the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933 with the fundamental goal of achieving farmer stability by raising the value of crops, which necessitated reducing crop surplus. Roosevelt appointed Wallace secretary of agriculture, Tugwell an undersecretary, and Peek administrator of the newly created Agriculture Adjustment Administration, the agency overseeing implementation of the AAA.

The AAA called for payments, or subsidies, to farmers to reduce certain crops, dairy produce, hogs, and lambs. Funding was derived from a tax on food processors of these same products. Reductions would eliminate surpluses, thereby returning farm prices to a reasonable level and allowing farmers recovery through economic relief and reform of the agricultural market. The year prior to the act, for example, cotton sold at the lowest price on record since the turn of the century, 5.1 cents a pound, having fallen from eighteen cents per pound in April 1929.

Although seven basic crops were controlled by the legislation, cotton was the dominant concern of Arkansas farmers. Arkansas’s cotton crop of 2,796,339 acres was already planted by the time the act passed. The Agricultural Adjustment Administration had to persuade Arkansas farmers to destroy a portion of the crop. Secretary Wallace announced a plow-up operation. The agency allocated Arkansas cotton farmers a crop reduction of thirty percent based on 1931 cotton production, when Arkansas cotton farmers planted 3,341,000 acres. Farmers needed to reduce 1,002,300 acres.

The agency had neither time nor labor to create a workforce to administer the new program. Cully A. Cobb—director of the Agricultural Adjustment Administration’s Cotton Division, a former Mississippi state extension official—approved the use of Agricultural Extension Service (AES) agents to oversee execution of the plow-up. University of Arkansas Cooperative Extension Service (UACES) director T. Roy Reid directed program implementation in Arkansas. The agency authorized farmer and citizen committees to help administer the program. Extension agents selected members to “county committees.” The largest and wealthiest farmers, together with bankers and merchants, were selected.

Reid and Dan T. Gray, dean of the College of Agriculture at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County), called a statewide meeting in Little Rock (Pulaski County) to explain the program’s elements to extension agents and county committee members. These individuals were to establish local committees for the groundwork and educate farmers at local gatherings on the basics of the program. The local committees would be responsible for the tasks of “enrolling farmers, inspecting pledged acreage, making yield estimations, and checking compliance with the plow-up agreements. The extension agents and county committeemen were to verify that local committees made reasonable estimates of the producer’s average yield, insure that all paperwork was completed correctly, and investigate and settle complaints,” according to Keith J. Volanto. AES agents also received and distributed subsidy checks.

“Cotton Week” kicked off the campaign. With enormous publicity, officials hoped for farmers’ acceptance with relatively little or no unwillingness to participate. Reluctance did surface, as did unanticipated complications—principally, a shortage of sign-up forms. Furthermore, some farmers disagreed with committeemen on estimated acreage yield, which would determine the amount of subsidy checks. In the end, 99,808 Arkansas farmers guaranteed 927,812 acres for destruction, twenty-five percent of the total Arkansas cotton acreage, consequently curtailing an estimated 395,480 cotton bales.

AAA achieved some success. Reduced production drove the price of cotton to more than ten cents per pound, a one-hundred-percent increase. Arkansas cotton farmers received $10.8 million in cash subsidies. Nevertheless, unanticipated results evolved from the program. With less cotton planted and subsidies paid to landowners, deceitful landowners were able to redirect their tenants and sharecroppers to day labor and seasonal workers, which forced some to migrate to big cities. Failing to receive a fair and evenhanded treatment, some tenants and sharecroppers formed the STFU in response. Cotton farmers also used empty land to test less labor-intensive crops and used subsidy checks to purchase tractors and other mechanical equipment, adding to the prospect of less-labor-intensive farming in the future. Farmer morale rose, increasing faith in government, and more farmers were exposed to the resources of the extension service.

In 1936, the Supreme Court declared the AAA unconstitutional by a vote of 6–3 in the case United States v. Butler, which centered upon a Massachusetts cotton mill that refused to pay the tax. The legislation failed in part because it taxed one farmer to pay another. Despite that setback, Congress found an acceptable solution and passed a second AAA in 1938 with funding coming from general taxation. The AAA emerged as the origin for farm subsidies and programs still in effect today.

For additional information:

Alexander, Donald Crichton. The Arkansas Plantation, 1920–1942. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1943.

Agricultural Adjustment Administration Annual Reports. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1933–1946.

Baker, J. A., and J. G. McNeely. Land Tenure in Arkansas IV. Fayetteville, AR: Agricultural Experiment Station, 1940.

Farm Tenancy: Report of the President’s Committee. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1937.

Fite, Gilbert C. Cotton Fields No More: Southern Agriculture 1865–1980. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1984.

———. George N. Peek and the Fight for Farm Parity. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1945.

Grubbs, Donald H. Cry from the Cotton: The Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union and the New Deal. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1971.

Nourse, Edwin G., Joseph S. Davis, and John D. Black. Three Years of the Agricultural Adjustment Administration. Washington DC: Brookings Institution, 1937.

Peek, George N., and Samuel Crowther. Why Quit Our Own. New York: Van Nostrand Co., 1936.

Perkins, Van L. Crisis in Agriculture: The Agricultural Adjustment Administration and the New Deal, 1933. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1969.

Richard, Henry I. Cotton under the Agricultural Adjustment Act: Developments up to July 1934. Washington DC: Brookings Institution, 1934.

U.S. Senate. Payments Made under the Agricultural Adjustment Program. Seventy-Fourth Congress, Second Session, Document 274. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1936.

Venkataramani, M. S. “Norman Thomas, Arkansas Sharecroppers, and the Roosevelt Agricultural Policies, 1933–1937.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 24 (Spring 1965): 3–28.

Volanto, Keith J. “The AAA Cotton Plow-Up Campaign in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 59 (Winter 2000): 388–406.

Woodruff, Nan Elizabeth. As Rare as Rain: Federal Relief in the Great Southern Drought of 1930–31. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1985.

———. “The Failure of Relief during the Arkansas Drought of 1930–1931.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 39 (Winter 1980): 301–313.

Whayne, Jeannie M. A New Plantation South: Land, Labor, and Federal Favor in Twentieth-Century Arkansas. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1996.

John Spurgeon

Bella Vista, Arkansas

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

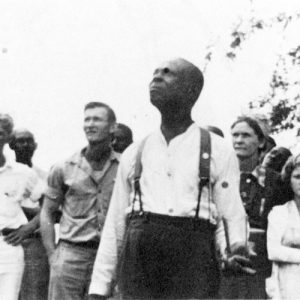

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Chopping Cotton

Chopping Cotton  Plowing a Cotton Field

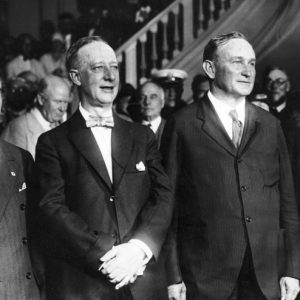

Plowing a Cotton Field  Joe T. Robinson

Joe T. Robinson  Southern Tenant Farmers' Union

Southern Tenant Farmers' Union

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.