calsfoundation@cals.org

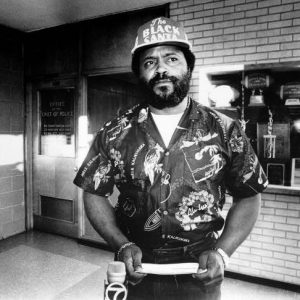

Robert "Say" McIntosh (1943–2023)

Robert “Say” McIntosh was a restaurant owner, political activist, and community organizer distinctly tied to the Little Rock (Pulaski County) area and Arkansas politics. A political gadfly during the 1980s and 1990s, McIntosh was responsible for many political protests that were statewide news during the time.

Say McIntosh was born in 1943 in Osceola (Mississippi County), the fifth of eleven children. In 1949, he and his family moved to the Granite Mountain area of Little Rock. McIntosh attended Horace Mann High School but dropped out in the tenth grade. He spent much of his early life learning the restaurant business, which led him to establish his own eatery, serving home-style cooking and his famous sweet potato pie. “The Sweet Potato Pie King of Little Rock,” as he was known, soon became an influential and charitable member of the local African American community, first making news for his free Thanksgiving dinner for hundreds of impoverished Little Rock residents in 1976. Thought to have earned the nickname “Say” by never missing an opportunity to voice his opinion or say something about an issue of importance to him or his community, McIntosh used his place as a community leader to try to effect change within Arkansas politics. McIntosh created Little Rock’s Black Santa Claus, distributing toys to the needy for years, which endeared him to the public but at times led to personal and financial hardship. His efforts saw him named Arkansan of the Year, and Governor David Pryor made December 24, 1976, Robert “Say” McIntosh Day.

In 1977, McIntosh staged the first of his many political protests. Unhappy at the prospect of liquor sales near his restaurant, he dumped empty bottles of beer and whiskey in the Alcohol Beverage Control Board offices. In 1978, he interrupted a volunteerism meeting to protest that there were no Black community leaders honored.

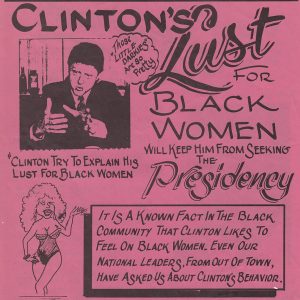

The 1980s marked the most prolific (and outlandish) period of McIntosh’s political career. McIntosh’s faux crucifixion in 1981 on the steps of the Arkansas State Capitol during a anti-racism demonstration targeting various state legislators and Governor Frank White nearly cost him his life when he suffered a heat stroke. The following year, McIntosh again made the news for posing as a homeless man to raise awareness of the growing epidemic of public drunkenness. In another protest staged for the press, McIntosh chopped down a tree planted in honor of Martin Luther King Jr., claiming that he did so because “[B]lacks were not involved in the political process in Little Rock.” Taking particular umbrage to the administration of Governor Bill Clinton, McIntosh began to post flyers around Little Rock with outrageous claims aimed at Clinton. His references to Clinton’s alleged infidelity (which McIntosh claimed had produced an illegitimate son) were distractions throughout Clinton’s gubernatorial administration and subsequent presidential campaign.

McIntosh also garnered coverage for his radical views on race, once inviting the Ku Klux Klan to a barbeque to welcome them to Little Rock. His most public display of radicalism was perhaps his 1990 live-television assault of Ralph Forbes, a white supremacist and Republican candidate for lieutenant governor; he then announced that he would support Forbes in the election. The assault had been in response to Forbes preventing McIntosh from burning an American flag at a protest the previous summer.

During the 1990s, McIntosh and others began to erect wooden crosses to represent the growing number of casualties of Little Rock’s gang-related violence. In 1992, his son Tommy was pardoned for his drug-related crimes by Jerry Jewell, then serving as acting governor while Governor Jim Guy Tucker was away. Controversy following the pardon resulted in a change to Arkansas constitutional law.

McIntosh continued to clash with political figures and local journalists until the end of the decade. During this time, McIntosh also faced many personal demons, including bankruptcy, continued arrests, allegations of assaults by those in the media, and the 1999 accusation that he poured hot grease on his son. McIntosh publicly melted down on camera on May 28, 1996, outside the federal courthouse in Little Rock when he repeatedly struck CNN producer Terry Frieden while trying to interrupt a live report by CNN reporter Bob Franken on the verdicts in the Whitewater trial of Governor Tucker.

While outrageous, McIntosh’s protests did bring to light the continued misrepresentation of African Americans in the local political process and the epidemic of violence and vagrancy that gripped the city. Some have even suggested that political opponents of those whom McIntosh maligned paid for some of his antics. If true, these claims would show that McIntosh was also a valuable political tool when needed. McIntosh said of his legacy, “What I was trying to do is get [B]lack people to stand up. That’s what it was all about.”

McIntosh ran Say McIntosh Restaurant and Pie Factory in Little Rock with his wife, Derotha. He died on June 24, 2023. In July 2024, his grandsons opened Say McIntosh Restaurant in Little Rock.

For additional information:

“Black Decks, Then Endorses White Supremacist.” Los Angeles Times, June 4, 1990.

Koon, David. “Say McIntosh: The Lion in Winter.” Arkansas Times, October 5, 2011, pp. 12–16, 18. Online at https://arktimes.com/news/cover-stories/2011/10/05/say-mcintosh-the-lion-in-winter (accessed October 30, 2025).

“McIntosh Gets a Date in Court over Fracas With CNN Producer.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, June 21, 1996, p. 14A.

Platt, Ainsley. “Activist Robert ‘Say’ McIntosh of Sweet Potato Pie Fame Dies.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, June 26, 2023, pp. 1B, 2B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/jun/26/robert-say-mcintosh-little-rock-activist-and/ (accessed October 30, 2025).

Robert “Say” McIntosh Materials. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Trimble, Mike. “Shadow Boxer: The Life and Times of Robert (Say) McIntosh.” Arkansas Times, June 1989, pp. 22–25, 42–44, 46.

Danny Russell

Arkansas State University

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.