calsfoundation@cals.org

Roark Bradford (1896–1948)

Roark Whitney Wickliffe Bradford was a popular journalist, novelist, and short story writer of the twentieth century. The subject matter of much of his fiction focused on African-American life, though in a humorous and stereotypical manner. Much of his inspiration is said to have been drawn from his childhood memories of growing up in Tennessee and Arkansas. His first book, Ol’ Man Adam an’ His Chillun (1928), was the basis for the 1930 Pulitzer Prize–winning drama Green Pastures.

Roark Bradford, born in Lauderdale County, Tennessee, on August 21, 1896, was the eighth of eleven children born to the farming family of Richard Clarence Bradford and Patricia Adelaide (Tillman) Bradford. In 1911, when he was approximately fourteen years old, his family moved to near Cabot (Lonoke County). It was during these impressionable years, while visiting the local African-American community, that he gathered much of the material for his writing career. In 1914, with the outbreak of World War I, he enlisted in the U.S. Army, serving as a first lieutenant of artillery in the Panama Canal Zone. He remained in the army after the war and served as a ballistics instructor until 1920 and briefly as a military science instructor at Mississippi A&M College at Starkville (now Mississippi State University).

Sometime after the war, he married Lydia Sehorn, with whom he had one son. It is believed that she contracted tuberculosis sometime in the late 1920s or early 1930s and died at New Mexico’s Sunmount Sanatorium in the 1930s. He later married Mary Rose Sciarra Himler.

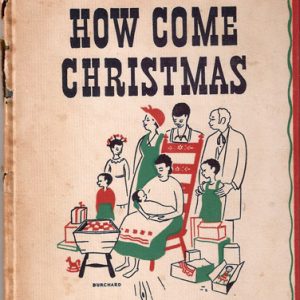

Bradford began his writing career as a journalist with the Atlanta Georgian in 1920. In 1924, he moved to New Orleans, Louisiana, becoming the night editor, and later the Sunday editor, of the New Orleans Times-Picayune. In 1926, he left the newspaper to pursue a freelance career as a fiction writer. Bradford developed his writings around stereotypical, humorous African-American characters. His first published work with such characters appeared as a series in the New York World that same year. His story titled “Child of God,” published in Harper’s Magazine, won the O. Henry Award for 1927. In 1928, the World series was published as Ol’ Man Adam an’ His Chillun. Some two years after publication, playwright Marc Connelly adapted the stories into a play titled Green Pastures. The well-received play won the 1930 Pulitzer Prize for Drama and, in 1936, was produced as a movie with an all-black cast. Bradford’s short story “John Henry,” which chronicled the exploits of the title character who spent some time in Arkansas, was a Literary Guild selection in 1931.

Bradford continued to produce well-received work during the 1930s and early 1940s. He served in the U.S. Naval Reserve Bureau of Aeronautics Training during World War II. In 1946, he accepted a position as visiting lecturer in the English department at Tulane University in New Orleans.

On November 13, 1948, he died of amebic dysentery, believed to have been contracted while he was stationed in French West Africa in 1943. His cremated remains were spread over the waters of the Mississippi River.

At the time of his death, Bradford’s writings were very popular. Since the 1940s, however, much of his body of work has been reevaluated. Many criticize his work as patronizing and demeaning in its portrayal of black characters.

For additional information:

“The Bradfords.” Arkansas Gazette. March 24, 1948, p. 4.

Kunitz, Stanley, and Howard Haycraft, eds. Twentieth Century Authors: A Biographical Dictionary of Modern Literature. New York: H. W. Wilson Co., 1942.

“Roark Bradford, Famed Author, Former State Resident Dies.” Arkansas-Democrat. November 14, 1948, p. 2A.

Smith, Martin S., and Andrew C. Kimmons, eds. World Authors, 1900–1950. Vol. 1. New York: H. W. Wilson Co., 1996.

Mike Polston

CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

I can’t understand critics who call Bradford a racist, classify his stories as a “crude caricature of Black folklore,” and despise his language as an “exaggerated Negro dialect.” Their essence can mostly be traced back to Sterling A. Brown’s “Negro Character As Seen by White Authors” in the Journal of Negro Education 2 (April 1933): 179-203. He starts with quotations from the first two pages of Bradford’s foreword to the first edition (Harper & Brothers, 1928). Unfortunately the reprints don’t contain that foreword, so you can’t detect that his quotations are out of context; he hasn’t understood the real content; and he had not the faintest idea about the remaining 260 plus pages either. The same applies to most of Bradford’s recent critics too. Consider the following from that foreword (they might explain, too, why it is missing in the reprints…):

“The nigger…has not learnt many of the finer points of our white civilization, such as intolerance, moral justification, fixed purposes, determination to win, high-pressure living, hate (in its extended sense), cold blooded business service, money as basis of all values, the effect of what people think about an individual as a governing factor of personal conduct, and so on…”[XII] “… he hasn’t learned yet to survey the facts in any situation and to relate them artfully so as to deceive and then justify his action by shifting the responsibility to the other fellow for not perceiving the deception.” [XIII]

“But, on the other hand, he has done three things in the past two hundred years that the white man hasn’t been able to do in two thousand years. He has created for himself a language of beauty and rhythm that, perhaps, is more expressive and less verbose than any language extant…” [XIII] In this language “…even the most ignorant Negro can get more said with a half dozen words than the average United States Senator can say in a two-hour speech.”[XIV] “…He has created him a religion that produces for him that spiritual peace and rest in this life that the religions of the white men describe and offer but fall just short of producing. And finally, he has produced a distinct racial music which, I believe, is not even claimed by any other race.”[XIV]

Sources: Ol’ Man Adam an’ His Chillun. Harper & Brothers Publishers, New York and London 1928, Foreword