calsfoundation@cals.org

Argenta Race Riot of 1906

aka: Lynching of Homer G. Blackman

Ignited by the slayings of two African American men in separate incidents the previous month, racial animosity flared up in Argenta (now North Little Rock in Pulaski County) in early October 1906, leading to the violent deaths of three more men over four days, including the lynching of Homer G. Blackman (called in some reports Homer Blackwell), a Black restaurateur. Local authorities imposed martial law and provided additional officers in an effort to quell hostilities. However, before order was restored, half a block of commercial buildings on East Washington Avenue burned down, two African American residences went up in flames, and scores of Black families temporarily left the city as armed men roamed the streets.

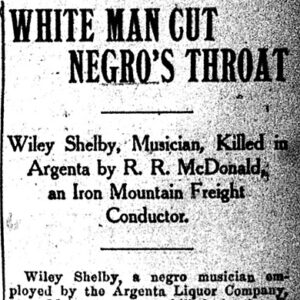

The two major newspapers in Little Rock, the Arkansas Gazette and the Arkansas Democrat, reported that the trouble stemmed from a barroom fight in which a white former Argenta policeman, Robert R. McDonald, killed a Black musician, Wiley Shelby, on September 11, 1906. Coroner S. Paul Vaughter attempted to convene an inquest into Shelby’s death the next day at the Black-owned Colum Brothers Funeral Home at 505 East Washington Avenue, but a melee interrupted the proceeding after Garrett Colum, who operated the funeral home with brothers Charles and Robert, attacked Milton Lindsey, a white Argenta patrolman, for blocking a group of Black people from entering the premises. During the confusion, two shots rang out, and Robert Colum fell dead from gunshot wounds. A jury, appointed by Justice of the Peace Frank P. Vaugine, ruled on September 13, 1906, that Robert Colum “met his death at the hands of someone unknown,” the Democrat reported that afternoon. The newspaper noted elsewhere in the September 13 edition that the coroner’s jury heard testimony concerning Shelby’s death and found that McDonald had acted in self-defense.

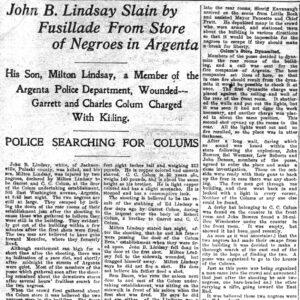

On the evening of October 6, 1906, John B. Lindsey, a farmer, and Milton Lindsey, his son, were ambushed as they walked in front of the Colum establishment. The elder Lindsey died from eleven gunshot wounds, and the younger suffered injuries. Police officers who tried to enter the Colum business were met with gunfire, and some fifty or sixty armed white men gathered across the street. Argenta mayor William C. Faucette, on advice from Police Chief Gabe Pratt and Pulaski County sheriff Coburn C. Kavanaugh, closed the saloons to forestall a riot. Faucette also ordered a ban on carrying firearms, except for sworn officers, and prohibited anyone from making inflammatory public statements. Charged with murder in Lindsey’s death were Garrett and Charles Colum, along with Louis Styles, a Black shoe store owner two doors down from the Colums, but the three men had escaped by the time Faucette and a posse of fifty men stormed the Colum’s building. The posse then went to Charles Colum’s home at 1517 East Second Street, where someone fired a shot at one of his sons.

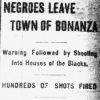

Overnight, fires engulfed Garrett Colum’s home at 1600 East 2nd Street and Styles’s house at 522 Locust Street. An African-American eyewitness told the Democrat that members of the mob tried to force the women and children back into Colum’s house after it was set afire, “but that later cooler heads came into control” and allowed them to flee. The paper quoted a newspaperman on the scene who said he heard about the incident but did not see it because he was on the other side of the house. Meanwhile, on East Washington, fire destroyed four buildings, including several businesses, both Black- and white-owned, in the early morning hours of October 7. Rumors ran wild for the next few days, and fears of arson in Argenta’s Black-populated east end convinced many to leave until calm was fully restored several days later. Scipio A. Jones, an African-American civil rights lawyer, arranged shelter in Little Rock (Pulaski County) for the Colum families. Many others stayed, among them women and children who gathered for protection at Shorter College and at the Hillside school in the Black community of Military Heights. With a force of some twenty additional officers, the police guarded these places and posted men to ensure the safety of Black workers at the railroad yards, cotton oil mills, and compress factories.

Homer G. Blackman, who shared an East Washington building with Styles, was arrested on October 7, 1906, for allegedly firing at the Lindseys. That evening, four masked men seized Blackman from the Argenta city jail and marched him, as others watched, to the corner at Sixth and Main streets, where they hanged him from a utility pole and shot him multiple times. A coroner’s jury concluded that Blackman died “at the hands of parties unknown,” the Democrat reported the next day. The Gazette maintained that Blackman was innocent of the charge because he did not arrive back by train from Lake Village (Chicot County) in time to have been in Argenta when the Lindseys drew fire. However, according to the Democrat on October 9, 1906, a witness reported seeing Blackman run from his restaurant two doors down from the Colums’ building with a pistol in hand immediately after shots were fired at the Lindseys.

On October 9, 1906, Alex Champion, a Black bartender, was shot and killed in the Bridge Saloon at the foot of the free bridge for allegedly making threats against Luther Lindsey, a deputy sheriff and a son of John B. Lindsey. A murder charge against Luther Lindsey in connection with Champion’s death was dismissed.

The historical record is sketchy as to what happened to the fugitives. Last word in the newspapers was that the three remained as fugitives and had possibly escaped to Indian Territory in Oklahoma. The events of September and October in 1906, while sending a hateful reminder of African Americans’ second-class legal standing, did not slow the economic and social progress of Argenta’s Black citizenry. On October 7, 2023, a marker was placed in downtown North Little Rock, at the corner of 6th and Main, honoring Homer Blackman/Blackwell.

For additional information:

Bowden, Bill. “NLR Marker to Honor 1906 Lynching Victim.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, September 30, 2023, pp. 1B, 8B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/sep/30/marker-to-honor-black-man-lynched-in-nlr-in-1906/ (accessed October 2, 2023).

“Colum Brothers Are Still At Large: Many Rumors Abound.” Arkansas Democrat, October 9, 1906, p. 1

“Colum Building Burned to Ground.” Arkansas Gazette. October 7, 1906, p. 1

“John B. Lindsay Slain by Fusillade From Store of Negroes in Argenta.” Arkansas Gazette, October 7, 1906, p.1

“John Lindsey Dead At Hands of Assassins, Blackwell Lynched By Determined Men.” Arkansas Democrat, October 8, 1906, p. 1.

Lancaster, Guy. “Before John Carter: Lynching and Mob Violence in Pulaski County, 1882–1906.” In Bullets and Fire: Lynching and Authority in Arkansas, 1840–1950, edited by Guy Lancaster. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2018.

Ly, My. “NLR Marker Honors Lynched Man.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, October 10, 2023, pp. 1B, 3B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/oct/08/nlr-dedicates-memorial-to-black-man-lynched-in/ (accessed October 10, 2023).

“Negro Undertaker Killed at Inquest In Argenta Today.” Arkansas Democrat, September 12, 1906, p. 1

Cary Bradburn

North Little Rock History Commission

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Race Riots

Race Riots Article about the Argenta Race Riot of 1906

Article about the Argenta Race Riot of 1906  Argenta Race Riot Article

Argenta Race Riot Article  Argenta Race Riot Article (Part 1)

Argenta Race Riot Article (Part 1)  Argenta Race Riot Article (Part 2)

Argenta Race Riot Article (Part 2)  Argenta Street Scene

Argenta Street Scene  Scipio Jones

Scipio Jones

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.