calsfoundation@cals.org

Diamond Mining

Almost 100 million years ago, in what is now Pike County, nature created one of the world’s most unusual diamond-bearing formations, the big volcanic “pipe” that now serves as the centerpiece of Crater of Diamonds State Park. Famous today for recreational mining, the eroded old crater once inspired generations of diamond hunters to dream of commercial success. The history of that long quest—the expectations, the contention, and the repeated frustration—is, in itself, an invaluable legacy of the Arkansas diamond field.

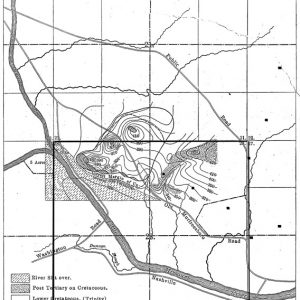

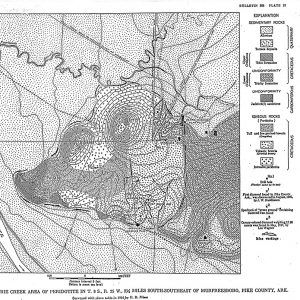

Unlike the typical diamond pipe, the formation in Pike County accumulated in various stages as molten rock deep within the earth’s mantle swept up through a shallower zone where diamonds had crystallized long before and then worked its way to the surface. Much of this magma rose slowly in a thick mass, apparently allowing intense heat and pressure to disintegrate (“resorb”) the crystals conveyed. Later, in sharp contrast, another part was caught up in at least one violent, gaseous eruption that fragmented the rock and cooled it enough to let diamonds survive. In the end, three distinct forms of the original magma spread across at least eighty acres at the surface. The diamond-bearing section dominated the east half of the structure.

Although the formation was recorded decades earlier, the search for diamonds began in 1888 when State Geologist John C. Branner and chemist Richard N. Brackett conducted a thorough survey and classified the rock as “peridotite”—an olivine material similar to the “blue ground” of the rich diamond-bearing pipes found recently in South Africa (later known as “kimberlite”). Because of baseless mining “excitements” at the time, Branner’s report refrained from mentioning the many fruitless hours he spent on hands and knees “looking for diamonds in the gullies and over the surfaces of the decomposed rocks.”

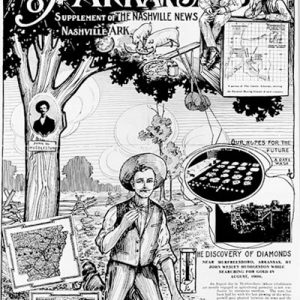

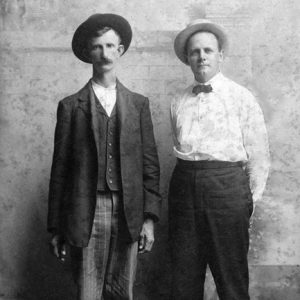

Successful hunting would have made Branner the first person outside of South Africa to discover diamonds at their original source. Instead, it was John Wesley Huddleston who accidentally saw the first crystals in the summer of 1906, on the surface of his farm near Murfreesboro (Pike County). That 243-acre tract, purchased in July 1905, included over three-fourths of the volcanic formation.

Beginning in September, an alert group of Little Rock (Pulaski County) businessmen led by Samuel W. (Sam) Reyburn, a leading banker-lawyer, obtained options on Huddleston’s land and most adjacent properties, securing control of all the formation except six acres at the northeast corner. Following Huddleston’s lead, the new venture began at the base of a big slope on the southeast side of the formation and soon found an extraordinary number of diamonds at the surface. Erosion had concentrated these within a layer of rocky, humus-enriched “black gumbo” averaging about one foot thick and extending at places to four feet. They usually turned up after vegetation was cleared but also could be screened from the topsoil with even the most primitive equipment.

In following tests, the black surface layer proved consistently diamond-rich. The highest recorded average yield ran slightly over thirty-six carats per 100 loads (the standard 1,600-pound tram load). Although exceptional, the yield would have run considerably higher if the equipment of that time had retained very small diamonds instead of letting them pass back onto the field. Further losses occurred unintentionally because of the tough clay gumbo.

Field workers finally dealt with the black gumbo by adopting a technique applied in Western gold fields—using high-pressure water hoses to break down the soil and flush material through sluice boxes, where heavy minerals were collected for regular processing. Between 1914 and December 1932, sluicing crews usually involving Lee J. Wagner of Murfreesboro stripped the surface layer from over fifty percent of the big southeast slope.

Of perhaps 20,000 diamonds recovered, three were unusually large for the Pike County formation: a canary-yellow beauty weighing 17.86 carats (1917); a fair 20.25-carat white specimen (1921), and the record-setting Uncle Sam Diamond, a brilliant 40.23 carats (1924). The overall yield averaged about ten percent gem quality, with the remainder an exceptionally hard industrial grade. Even the industrials usually had an attractive natural luster in the rough. Experts declared the gems at least as brilliant and valuable as those produced in South Africa or South America.

In the first few years of testing, the surface yield and the size of the formation—then estimated at sixty to seventy surface acres—led almost all the experts to believe commercial-grade zones would likely turn up in the peridotite matrix at some point. Reyburn’s most experienced diamond-mining engineer, John T. Fuller, was so “confident of ultimate success” that his reports in 1908–1912 often left the impression the surface yields represented the commercial potential of the southeast slope.

The big formation lost very little respect as it became apparent that the diamonds were coming from some thirty-five acres on the east side. That productive “volcanic breccia,” as the U.S. Geological Survey classified it, still covered a surface area larger than any of the original South African pipes.

Compounding the excitement, prospectors soon found other peridotite deposits near the first discovery. The American Mine, the Kimberlite Mine, the Black Lick, and various imagined finds became the targets of new ventures such as the American Diamond Mining Company; the Kimberlite Diamond Mining and Washing Company, headed by Midwesterners Austin Q. Millar and son, Howard A.; and the Ozark Diamond Mining Company, reorganized in 1909 as the Ozark Diamond Mines Corporation. After this speculative heyday faded in 1909, the American and Kimberlite companies continued probing their properties for about two years; but in the end, the remarkable burst of activity produced very little except crushed expectations and growing skepticism.

The big formation itself raised doubts whenever Sam Reyburn’s group, finally organized as the Arkansas Diamond Company (ADC), concentrated on the crucial matrix. The highest recorded yield from “peridotite” on the southeast slope came from 482 loads washed in 1909: an average of two carats per 100 loads, or only about one-sixth of the average needed for minimal commercial production. A full-scale test of 45,961 loads in 1920–1922 was affected by problems at the ADC’s new plant; yet, the average of 0.38 carat per 100 clearly demonstrated the fatal limitations of the matrix.

After 1922, the ADC worked the surface for almost three years before halting all activity. In 1928, Reyburn’s group withdrew fully from the operation and left it to other Little Rock businessmen, who then leased the property to a new venture guided by John Fuller—the Arkansas Diamond Mining and Engineering Company. Finally, in July 1930, the struggling ADC dissolved after transferring all properties to its financing partner, the Arkansas Diamond Corporation of Virginia. Fuller’s associates retained their lease but worked only the surface until the Great Depression ended all activity in late 1932.

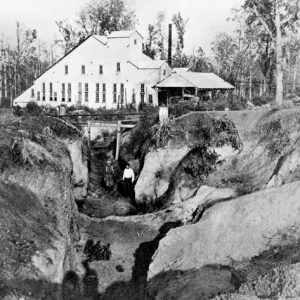

The ADC’s experience was repeated on a much smaller scale on the northeast slope. The Ozark group persuaded the owner, Millard M. (M. M.) Mauney, to sell four of the six acres and, in 1912, built the first full-size “crushing and recovery plant.” Concentrating on the matrix, the corporation processed about 5,000 loads from a huge trench before declaring bankruptcy the following spring.

In 1912, Mauney leased the remaining two acres to Austin Millar’s Kimberlite Company, along with a plant site at nearby Prairie Creek. In early 1913, the elder Millar, an experienced diamond prospector, began digging pits to evaluate the matrix and, after weeks of labor, reported six small diamonds. Later, a “special careful test” of 250 loads of the basic blue ground yielded fourteen diamonds totaling slightly over one carat.

Howard Millar, a young mining engineer, temporarily resolved the crisis by switching to long shallow trenches, a method exploiting the richer surface material. In 1915–1916, the trenching extended eastward into the Ozark Mine after the Millars managed to buy that property. Careful testing produced averages of about eleven carats per 100 loads from the Mauney Mine and ten to eleven per 100 from the Ozark—figures high enough to suggest commercial potential and appeal to investors. Still, the Kimberlite Company soon lost investor support and sank into debt. On the night of January 13, 1919, mysterious fires ravaged buildings and equipment at both the Prairie Creek site and the Ozark property, permanently terminating the Millars’ field operations.

After the Depression, the earlier reports of John Fuller and the Millars helped various mining interests press for renewed testing of the dormant Pike County field. The U.S. Bureau of Mines responded in 1943–1944 with its own evaluation of the southeast slope: slightly less than two carats per 100 tons avoirdupois. Unsatisfied, the Diamond Corporation of America (the “Glenn Martin Company”) followed with a less efficient test of the entire formation in 1948–1949 and found almost 0.2 carat per 100.

After Crater of Diamonds State Park opened in 1972, the commercial campaign was enlivened by discoveries of both diamond-bearing kimberlite along the Colorado-Wyoming border and related olivine “lamproite” in Australia (the Argyle Mine). Inspired by the rich Argyle, geologists reclassified the Pike County deposits as lamproite. Some optimists speculated the big pipe could hold as much as $5 billion worth of diamonds.

After commercial pressure built in the 1980s, a joint state-private venture finally evaluated the entire pipe and, in 1997, reported an overall average of 0.57 carat per 100 metric tons. The historically defined diamond field averaged about one carat per 100 tons. Concluding the affair, the State Parks, Recreation and Travel Commission voted to impose a twenty-year ban on further applications for commercial testing; the legislature followed with a permanent ban.

Today, the ancient volcanic pipe fills a compatible role as regular “diggers” and other recreational miners work the plowed thirty-five-acre field. Notably, a large number of diamonds found at the state park have come from a network of buried drainage channels holding material left from the processing of the surface layer in the early commercial era.

For additional information:

Banks, Dean. “Arkansas Diamonds: Dreams, Myths, and Reality.” Condensed edition of unpublished manuscript (1997), 2006. Pike County Archives and History Society. http://o.pcahs.org/Arkansas_Diamonds/idxFr2.htm (accessed August 17, 2023).

Bassoo, Roy Raymond, Jr. “Guiana Shield Diamonds, the Sub-Cratonic Lithosphere, and Kimberlite Emplacement in the Upper Crust.” PhD diss, Baylor University, 2021.

Bassoo, R., S. Eaton-Magaña, M. F. Hardman, C. M. Breeding, K. Befus, and Je. E. Shigley. “The Morphology and Spectroscopy of Diamonds Recovered from the Prairie Creek Lamporite in Arkansas, USA.” Mineralogical Magazine, January 15, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1180/mgm.2024.92 (accessed January 21, 2025).

Branner, John C., and R. N. Brackett. “The Peridotite of Pike County, Arkansas.” American Journal of Science 38, 3d Series (1889): 50–59.

“Crater of Diamonds.” Microfilm collection. Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Dunn, Dennis P. “Zenolith Mineralogy and Geology of the Prairie Creek Lamproite Province, Arkansas.” Ph.D. diss., University of Texas at Austin, 2002.

Fuller, John T. “The Arkansas Diamond Field.” Engineering and Mining Journal 93 (January 6, 1912): 6.

———. “The Arkansas Diamond Field in 1909.” Engineering and Mining Journal 89 (April 9, 1910): 767–768.

———. “Arkansas Diamond Field in 1910.” Engineering and Mining Journal 91 (January 7, 1911): 6.

———. “The Arkansas Diamond Field in 1913.” Engineering and Mining Journal 97 (January 10, 1914): 52.

———. Diamond Mining in Arkansas.” Engineering and Mining Journal 95 (January 11, 1913): 75.

———. “Diamond Mine in Pike County, Arkansas.” Engineering and Mining Journal 87 (January 16, 1909): 152–155.

———. “Diamond Mine in Pike County, Arkansas.” Engineering and Mining Journal 87 (March 20, 1909): 616–617.

Fuller, John T., et al. “Reports and Information Gathered by John T. Fuller from 1908 to 1931—Diamond Fields in Pike County, Arkansas.” On file at Arkansas Department of Parks and Tourism, Little Rock, Arkansas. On microfilm at Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkanas.

Henderson, John C. “The Crater of Diamonds: A History of the Pike County, Arkansas, Diamond Field, 1906–1972.” PhD diss., University of North Texas, 2002.

Kunz, George F., and Henry S. Washington. “Diamonds in Arkansas.” In Transactions of the American Institute of Mining Engineers, 1908. New York: AIME, 1909.

Lancaster, Bob. “Diamonds: Does Arkansas Have a $5 Billion Future?” Arkansas Times, March 1983, pp. 59–70, 72.

Leveritt, Mara. “Bewitched, Botched, and Bedazzled.” Arkansas Times, November 1988, pp. 72–78.

———. “Field of Dreams.” Arkansas Times, July 9, 1992, pp. 22–23.

Millar, Howard A. It was Finders Keepers at America’s Only Diamond Mine. New York: Carlton Press, 1976.

Miser, Hugh D., and A. H. Purdue. “Igneous Rocks.” In Geology of the De Queen and Caddo Gap Quadrangles, Arkansas. Bulletin 808. Washington DC: U.S. Geological Survey, 1929.

Morgan Worldwide Mining Consultants. “Crater of Diamonds State Park Evaluation Program, Final Report.” Little Rock: Arkansas State Parks, Recreation and Travel Commission, 1997.

Peacock, Leslie. “The Great Arkansas Diamond Hunt.” Arkansas Times, February 25, 1993, p. 10.

Petty, Willard Brian. “Finders Keepers: The American Diamond Legacy.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2009.

Thoenen, J. R., et al. Investigation of the Prairie Creek Diamond Area, Pike County, Ark. Report of Investigations 4549. Washington DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Mines, 1949.

Dean Banks

Murfreesboro, Arkansas

ADC Workers

ADC Workers  Black Gumbo Sluicing

Black Gumbo Sluicing  Crater of Diamonds

Crater of Diamonds  Diamond Discovery Announcement

Diamond Discovery Announcement  Diamond Grease Table

Diamond Grease Table  Diamond Pipe Map

Diamond Pipe Map  Diamond Washing

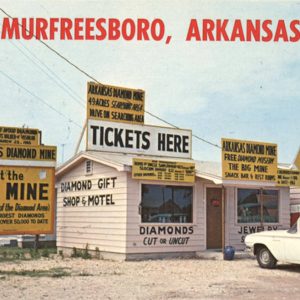

Diamond Washing  Diamond Mine Advertising

Diamond Mine Advertising  Diamond Mining Company

Diamond Mining Company  Diamond Survey, 1888

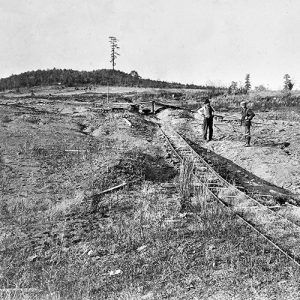

Diamond Survey, 1888  Early Diamond Exploration

Early Diamond Exploration  John Huddleston and Sam Reyburn

John Huddleston and Sam Reyburn  Map of Peridotite for Diamond Mining

Map of Peridotite for Diamond Mining  Mauney Mine

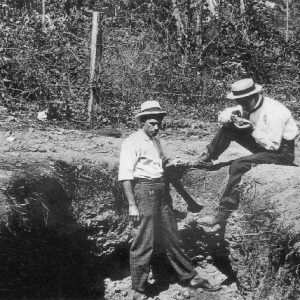

Mauney Mine  Millars at the Ozark Diamond Mine

Millars at the Ozark Diamond Mine  Murfreesboro Postcard

Murfreesboro Postcard  Ozark Mine Plant

Ozark Mine Plant  Southeastern Slope

Southeastern Slope  Uncle Sam Diamond Rough

Uncle Sam Diamond Rough

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.