calsfoundation@cals.org

Engagement at Old River Lake

aka: Engagement at Ditch Bayou

aka: Engagement at Lake Chicot

aka: Engagement at Lake Village

aka: Engagement at Furlough

aka: Engagement at Fish Bayou

aka: Engagement at Grand Lake

| Location: | Chicot County |

| Campaign: | Expedition to Lake Village |

| Dates: | June 6, 1864 |

| Principal Commanders: | Brigadier General A. J. Smith (US); Colonel Colton Greene (CS) |

| Forces Engaged: | Two brigades of XVI Army Corps (US); Greene’s Confederate Cavalry (CS) |

| Estimated Casualties: | 131 (US); 37 (CS) |

| Result(s): | Union victory |

On June 6, 1864, Union and Confederate forces clashed along the southern shore of Lake Chicot near Lake Village (Chicot County). The engagement at Old River Lake (also known as Ditch Bayou) was the largest to occur in Chicot County and the last significant Civil War engagement in Arkansas. Union forces won the field but suffered higher casualties.

By the end of 1863, Union forces controlled almost all traffic on the Mississippi River. Steamships were the primary sources of transportation. Gunboats protected fleets of troop transports moving up and down river. Their large cannons bombarded areas of Rebel activity along the river bank. Landing parties foraged for food and burned plantations. Local inhabitants lived in terror at the approach of military men in any uniform.

In May 1864, a Confederate force of cavalry and artillery under the command of Major General John S. Marmaduke arrived in Chicot County and began attacking Union vessels. Their field commander was Colonel Colton Greene. Greene used the long, twisting river channel to his advantage. In some locations, ships had to navigate long river bends separated by narrow necks of land. Steamships moving slowly upriver, with a top speed of thirteen miles per hour, made good targets. Confederate batteries waited until ships had passed before firing at their sterns, where they were most vulnerable. When the vessels being attacked were out of range and continuing up river, the Confederates quickly moved their artillery across the narrow necks to attack the same vessels.

In less than two weeks, the Confederates inflicted heavy damage on river traffic. Greene reported, “I engaged 21 boats of all descriptions, of which five gunboats and marine-boats were disabled, five transports badly damaged, one sunk, two burned, and two captured. My loss was one subaltern and five privates slightly wounded. No guns or horses were hit. The river is blockaded.”

Greene’s success in blockading river traffic meant that Union forces were needed in Chicot County. On June 5, 1864, twenty-eight steam vessels landed near the southern tip of Lake Chicot. On board were 6,000 men under the command of General Andrew Jackson Smith.

Only half of the Union force disembarked. Some skirmishing occurred that evening, but only a few casualties were reported. Confederates tested the Union forces’ strength while making plans for the battle that was sure to follow.

Greene’s command at that time consisted of ten artillery pieces and 800 men. One battery (four cannons) was sent with 100 men to Lake Village to protect against a possible attack from the north. Another 100 men were sent to guard a bridge that was to be used as an escape route to the west. This left Pratt’s Texas artillery of six cannon and 600 Missouri cavalrymen to hold back the Union force of 3,000, mostly infantry from Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, and Wisconsin. Among them was Old Abe, a bald eagle carried as a mascot of the Eighth Wisconsin. The Confederates would use Ditch Bayou, a deep and muddy waterway with steep banks leading southward from Lake Chicot, and the terrain to their advantage.

On the following morning, June 6, rain fell as the Union forces broke camp, formed a column, and marched toward Lake Village. The rain would become an important factor in the battle and its casualties. Confederate skirmishers were sent to delay the Union column. Greene kept most of his men hidden in trees along the western bank of the bayou.

As the Union force advanced, Confederate skirmishers fell back eventually across Ditch Bayou. The only bridge over the bayou was destroyed by Confederates after the last of their men reached the west side of the bayou. The Union force formed an orderly front nearly a mile long. Their artillery was mired in mud. Without knowing that a moat-like bayou separated the two forces, Union officers ordered their men to advance across what they thought was an open field about 700 yards wide.

Confederate artillery, hidden in timber near the bridge, showered the Union line with exploding shells and canisters. Advance troops became pinned down in the open. They could not advance because of the bayou and they could not rise up in order to retreat for fear of being shot. Rifle and cannon smoke shrouded the wet, muddy battlefield. The smoke both protected the Unionists from their enemy and prevented them from attacking in mass.

Union cavalry managed to cross the bayou south of the battlefield. This flanking movement and low ammunition supplies forced the Confederates to begin an orderly withdrawal at 2:30 p.m. Four of their men were killed, and thirty-three were wounded. Union casualties were much worse: thirty-three dead and ninety-eight wounded.

That night, the Union forces camped in Lake Village. All available houses were converted into hospitals for the wounded. Fences, chicken coops, out buildings, and everything that would burn was used for fires to warm, dry, and cook food for the thoroughly drenched men.

The following morning, the Union forces continued north along Lake Chicot. During the night, their transports had steamed upriver and were waiting at Luna and Columbia. Confederates skirmished with the Union rear guard until gunboats began shelling the area. Some looting and burning along the river was blamed on Union forces before they boarded their ships and steamed upriver.

The Union forces were unsuccessful in driving Confederates away from the river. Rebels sporadically harassed river traffic in the area for a few months. Marmaduke’s command participated in a Missouri raid and did not return to Chicot County.

For additional information:

Clarke, Norman E. Warfare along the Mississippi: The Letters of Lieutenant Colonel George E. Currie. Ann Arbor: Central Michigan University Press, 1961.

Shea, William L. “Battle at Ditch Bayou.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 39 (Autumn 1980): 195–207.

Simons, Don. In Their Words, A Chronology of the Civil War in Chicot County, Arkansas and Adjacent Waters of the Mississippi River. Sulphur, LA: Wise Publications, 2000.

Don R. Simons

Mount Magazine State Park

Civil War Events Map

Civil War Events Map  Ditch Bayou

Ditch Bayou  Ditch Bayou Marker

Ditch Bayou Marker  Old Abe

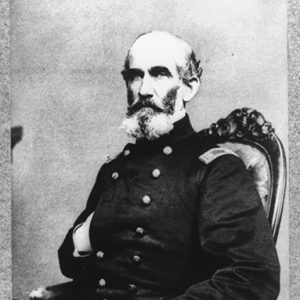

Old Abe  Andrew J. Smith

Andrew J. Smith

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.