calsfoundation@cals.org

Commonwealth College

Arkansas’s most famous attempt at radical labor education was the accidental by-product of natural beauty, cheap land, and desperation. Commonwealth College was established in 1923 at Newllano Cooperative Colony near Leesville, Louisiana. Its founders were Kate Richards O’Hare, her husband Frank, and William E. Zeuch, all socialists and lifelong adherents of the principles established by Eugene V. Debs. Drawing on their mutual experience at Ruskin College in Florida, where they had been impressed with the possibility of higher education combined with cooperative community, the O’Hares and Zeuch decided to create a college specifically aimed at the leadership of what they designated as a new social class, the industrial worker. As an established cooperative community, Newllano appeared to be the ideal host for this experiment. Alas, strong personalities and conflicting priorities made for immediate conflict between college and colony. Specifically, George T. Pickett, Newllano leader, and Zeuch, Commonwealth’s director, clashed repeatedly over a variety of issues to such an extent that, within months, it was clear that the college, if it was to survive, had to find a new home.

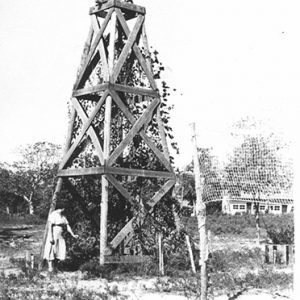

Searchers eventually located a beautiful site in Polk County, Arkansas, near the hamlet of Ink. Negotiations with the owners were quickly concluded, and the college began preparations to move to Arkansas. A number of disgruntled Newllano residents, including colony founder Job Harriman, opted to leave immediately for the new site, establishing the Commonwealth Community of the Ozarks to accommodate the college’s move to Ink. Given the strong personalities involved, it was inevitable that Harriman and his long time friend Ernst Wooster fell out with Zeuch and Kate O’Hare, and suddenly the Ink option was closed to the college. Not to be deterred, however, the school rented property in Mena (Polk County) and moved there in December 1924. On April 19, 1925, Commonwealth moved to its permanent home thirteen miles west of Mena, “a wonderful valley, perhaps a mile or more wide, running up to the edge of Rich Mountain, watered by a beautiful creek.” Like pioneers, the Commoners carved a campus out of this virtual wilderness while carrying on with schooling and tending crops. Its college building was made possible by critical financial help from Roger Baldwin’s American Fund for Public Service. The serenity of these exhausting early years was shattered in 1926, however, when the American Legion’s State Convention charged Commonwealth with Bolshevism, “Sovietism,” communism, and free love and moved to investigate and close the little school. The resulting uproar and unwanted publicity lasted several months and ended only when FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover denied that the college had any record of such ideas and activities. Though exonerated and at this point innocent, Commonwealth became permanently identified in the popular mind as “Red.”

This sort of publicity was anathema to Debsian socialist Zeuch, who supported theoretical labor education and communal living rather than active participation in radical reform movements. Zeuch established as Commonwealth’s original mission the production of sophisticated, literate, and idealistic leaders for the labor movement. The director and his followers were convinced that the development of a working class led by men and women who were inculcated with the principles of living according to need and working for common wealth and welfare was the only sensible road to a national or world cooperative commonwealth: community-based syndicates directed by caring and educated leaders would replace the current exploitation of the worker by corporate capitalists. Commonwealth’s unsettled curriculum always contained a core of liberal arts courses taught from a labor perspective. To safeguard this process, Zeuch tried desperately to maintain cordial relations with the college’s neighbors and to keep a low, uncontroversial public image.

This placid scenario changed abruptly in June 1931, when a student-staff revolt headed by longtime Commoner Lucien Koch seized control of the college, ousted Zeuch, and plunged Commonwealth into aggressive labor activity. The Great Depression had radicalized both students and faculty, and Zeuch’s vision of the cooperative commonwealth was deemed inadequate. Delegations of Commoners were sent to Harlan, Kentucky, and Franklin County, Illinois, to support coal miners in their strikes for union recognition. Other Commoners involved themselves in farm-labor organization, supporting the National Farmer’s Holiday Association and participating in strike activities in Corinth, Mississippi, and Paris (Logan County). College faculty and staff were prominent in the formation of a new Socialist Party in Arkansas in 1932, and Clay Fulks, an instructor at the school, was the party’s nominee for governor in 1932. All this activity generated a high profile for the tiny school, with charges of atheism, free love, and, most frequently, communism being heard throughout the South.

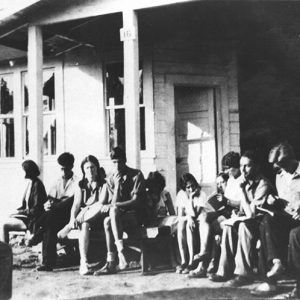

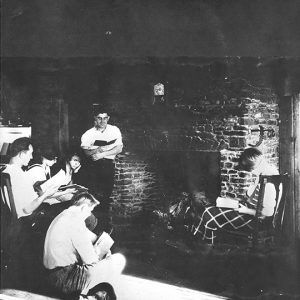

Notwithstanding the change in direction, Commonwealth always maintained the same pattern of day-to-day existence on campus. Traditional post-secondary education was designed for the middle class and was thus unsuitable for the industrial worker. The Commoners decided to eliminate all the “bourgeois claptrap” from their campus and create an “educational commune.” The schools strove to be self-sufficient by requiring four hours of labor per day from staff and students in return for subsistence and, in the case of students, instruction. Faculty members were not paid and were expected to participate in every campus activity, including farm work, maintenance, and anything else necessary to escape from “bourgeois interests.” Women worked primarily in the kitchen, the library, the laundry, and the school office, while men toiled on the wood crew, carpentry crew, farm crew, masonry crew, or hauling crew. Self-maintenance was never achieved; the Commoners could, at best, produce seventy percent of their subsistence. The continuing deficit had to be gleaned from constant fundraising and grants from radical sources, such as the American Fund for Public Service.

Classes began at 7:30 each morning and were usually held in the instructor’s cottage. The unvarying format was group discussion, occasionally heated. The college operated on a vague quarter system, and students were limited to three courses per quarter. Commonwealth gave no grades, conferred no degrees, and had no class attendance requirement. Classes seldom exceeded six students, and the total student body never numbered more that fifty-five. The college community, though small, was very cosmopolitan and included Americans from various ethnic groups (though no African Americans), all geographic sections, and every educational level. The only entrance requirements were intelligence, a sense of humor, and dedication to the labor movement. Commonwealth’s most famous student, Orval Faubus, in an interview just before his death, said that he had “never been with a group of equal numbers that had as many highly intelligent and smart people as there were at Commonwealth College.”

The new activist Commonwealth could not resist the lure of the organizational activities of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union (STFU) in eastern Arkansas. It was, for the college, a fatal attraction. Union leaders H. L. Mitchell, Howard Kester, and Gardner Jackson were determined to avoid the “Red” taint so closely associated with the school, yet the initial community of interests between the two labor entities was unavoidable. With great union reluctance, and after a violent initial organizational effort by a Commonwealth delegation, the school and the STFU moved to cooperate. The college would provide training for potential union leaders drawn from its tenant members. Commonwealth quickly submerged all of its other activities to focus on the STFU. The union became the college’s sole raison d’etre, but by 1936, the relationship was so acrimonious that the STFU and its national supporters, including Norman Thomas and Roger Baldwin, demanded a total reorganization of the college. Commonwealth accepted this ultimatum, but such changes as were incorporated were minimized by the school’s selection of radical Presbyterian minister Claude Clossey Williams as director. STFU leaders were terrified of Williams’s alleged communist sympathies, but for nearly two years, the reorganized college seemed to work well with the union. Union President J. R. Butler became an instructor at the school as well as a supporter of Claude Williams.

The union’s fears about Williams and the college suddenly seemed justified in August 1938, when a document surfaced that purported to be a detailed plan by the communists at Commonwealth to “capture” the union for the party. The scheme apparently had Williams’s approval. A shaken J. R. Butler led the STFU move to disengage the union completely from the college and Williams. By the end of the year, it was done, and Commonwealth had lost its reason for being and all of its moderate leftist support. The estrangement from organized labor, shattered finances, a dilapidated physical plant, and poisoned relations with its local neighbors dictated drastic action. Rejecting proposals to close or merge with Highlander Folk School at Monteagle, Tennessee, the Commonwealth College Association decided to soldier on and to make the school a drama center under the auspices of the radical New Theatre League of New York City. This was too much for local residents, and charges of anarchy, failure to fly the American flag during school hours, and displaying the hammer and sickle emblem of the Soviet Union were filed against the school in Polk County Court. The college was found guilty and fined a total of $5,000.00, which it could not pay. Appeals were fruitless, and all of Commonwealth’s property, real and otherwise, was sold to pay the fine. By the end of 1940, Commonwealth College had ceased to exist.

A 1935 mural painted by artist Joe Jones and displayed in the college’s dining hall, The Struggle in the South, was decades later acquired by archivists at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock and restored. It is now on display at UA Little Rock Downtown in the River Market district of Little Rock (Pulaski County).

For additional information:

Altenbaugh, Richard J. Education for Struggle: The American Labor Colleges of the 1920s and 1930s. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1990.

American Fund for Public Service Records. Rare Books and Manuscripts Division. New York Public Library, New York City, New York.

Cobb, William H. Radical Education in the Rural South: Commonwealth College, 1922–1940. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2000.

Commonwealth College Fortnightly. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas. http://libinfo.uark.edu/specialcollections/commonwealth/fortnightly.asp (accessed July 6, 2023).

Koch, Raymond, and Charlotte Koch. Educational Commune: The Story of Commonwealth College. New York: Shocken Books, 1972.

Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union Papers. Southern Historical Collection. University of North Carolina Libraries, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

St. John Collection of Commonwealth College Papers. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

William H. Cobb

East Carolina University

I thoroughly enjoyed the article on Commonwealth College. Both of my parents were from Mena: Wm. P. (Pascal) Alexander, son of Will Alexander, and India Dell Turner, daughter of Ode Turner.

My dad passed away when I was very young, but I remember pieces of the Commonwealth story and found this article fascinating. My understanding was that my dad was involved in the prosecution as county prosecutor.