Race and Ethnicity: African American - Starting with O

Oaks Cemetery

Oats, Presley (Lynching of)

Oliver, Dan (Lynching of)

One-Drop Rule

aka: Act 320 of 1911

aka: House Bill 79 of 1911

Original Tuskegee Airmen

aka: Tuskegee Airmen, Original

Original Tuskegee Airmen

Original Tuskegee Airmen

Owen, Hurley (Lynching of)

Silas Owens

Silas Owens

Owens, Silas

Owens, William (Execution of)

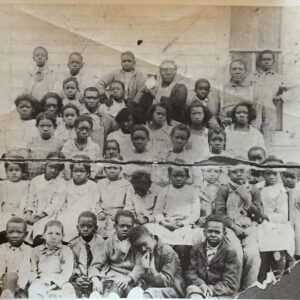

Ozan Students

Ozan Students