Entry Category: Civil Rights and Social Change - Starting with M

Mitchell, Elton (Lynching of)

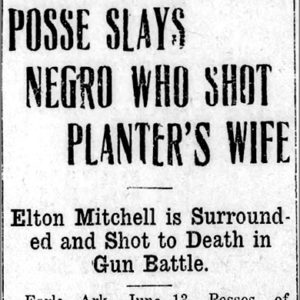

Elton Mitchell Lynching Article

Elton Mitchell Lynching Article

Harry Mitchell

Harry Mitchell

Mitchell, Harry Leland

James Mitchell

James Mitchell

Mitchell, Juanita Jackson

Mitchell, William Starr (Will)

The Modern Medea

The Modern Medea

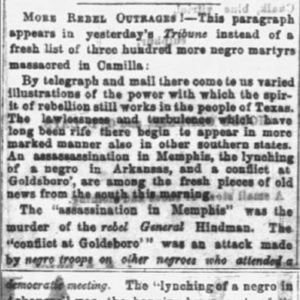

Monroe County Lynching of 1893

Frank Moore Memorial

Frank Moore Memorial

Frank Moore Tombstone

Frank Moore Tombstone

Moore v. Dempsey

Moore, Frank

Moroles, María Cristina DeColores

Morrison, Lee (Lynching of)

Lee Morrison Lynching Article

Lee Morrison Lynching Article

William Morrison Lynching Article

William Morrison Lynching Article

William Morrison Lynching Article

William Morrison Lynching Article

Mosaic Templars Headquarters

Mosaic Templars Headquarters

Mosaic Templars of America Seal

Mosaic Templars of America Seal

Mosaic Templars of America

Mosely, Julius (Lynching of)

Mothers’ League of Central High School

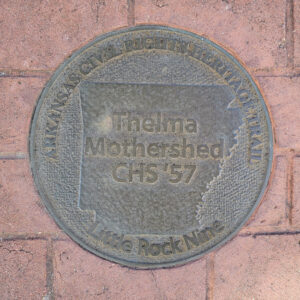

Mothershed Marker

Mothershed Marker

Mountain Home Lynching Article

Mountain Home Lynching Article

Mullens, Nat (Lynching of)

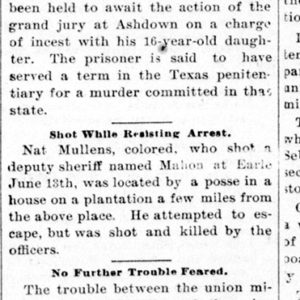

Nat Mullens Lynching Article

Nat Mullens Lynching Article

Multiculturalism

Murfreesboro Colored School

Murfreesboro Colored School