Entry Category: Civil Rights and Social Change - Starting with A

aka: Cooper v. Aaron

Abortion

Abrams, Annie Mable McDaniel

ACORN Action

ACORN Action

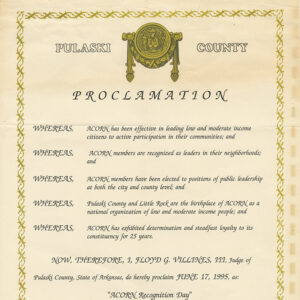

ACORN Certificate

ACORN Certificate

Act 10 of 1958 [Affidavit Law]

Act 115 of 1959 [Anti-NAACP Law]

Act 151 of 1859

aka: Act to Remove the Free Negroes and Mulattos from the State

aka: Arkansas's Free Negro Expulsion Act of 1859

Act 258 of 1909

aka: Toney Bill to Prevent Lynching

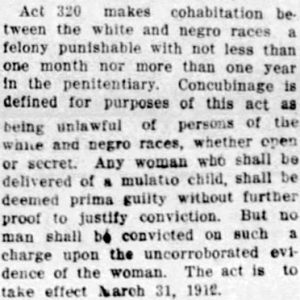

Act 320

Act 320

Act 626 of 2021

aka: Save Adolescents from Experimentation Act

aka: HB 1570

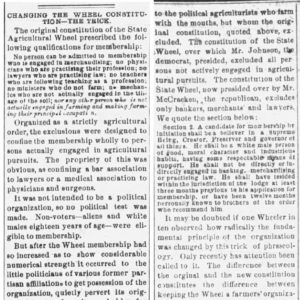

Agricultural Wheel Article

Agricultural Wheel Article

Dick Allen

Dick Allen

Allen, Dorathy N. McDonald

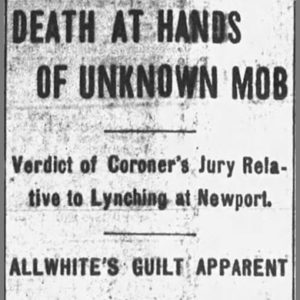

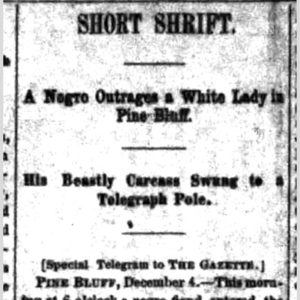

Allwhite Lynching Editorial

Allwhite Lynching Editorial

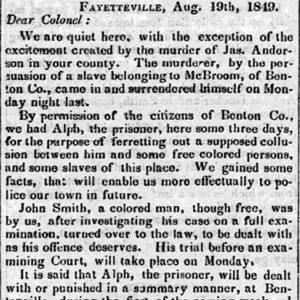

Alph Lynching Article

Alph Lynching Article

Alph (Lynching of)

American Association of University Women (AAUW)

American Civil Liberties Union of Arkansas

aka: ACLU of Arkansas

aka: Arkansas ACLU

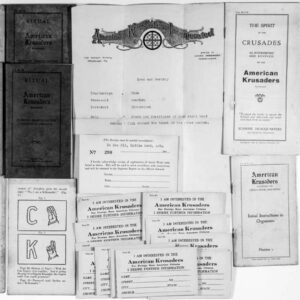

American Krusaders

American Krusaders Ephemera

American Krusaders Ephemera

American Missionary Association

Ameringer, Freda Hogan

Freda Hogan Ameringer

Freda Hogan Ameringer

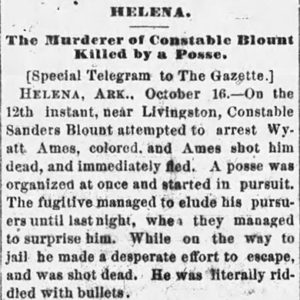

Ames, Wyatt (Lynching of)

Wyatt Ames Lynching Article

Wyatt Ames Lynching Article

Anderson, Andrew Lee (Killing of)

Anderson, James (Lynching of)

James Anderson Lynching Article

James Anderson Lynching Article

Anderson, William (Lynching of)

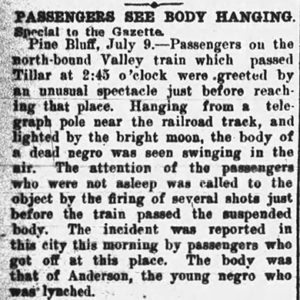

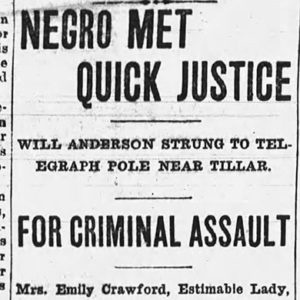

William Anderson Lynching Article

William Anderson Lynching Article

William Anderson Lynching Article

William Anderson Lynching Article

Anthony, Katharine Susan

Anti-miscegenation Laws

Anti-Semitism

AOUW Building

AOUW Building

Appeal of the Arkansas Exiles to Christians throughout the World

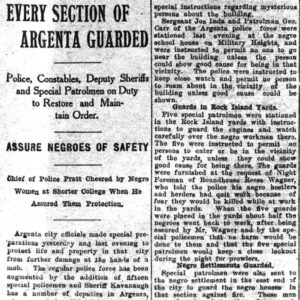

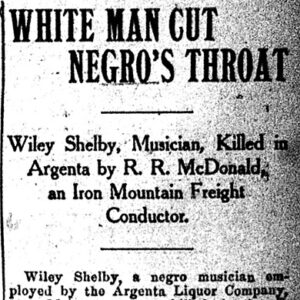

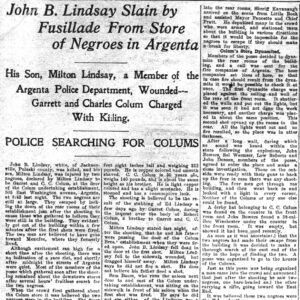

Argenta Race Riot Article

Argenta Race Riot Article

Article about the Argenta Race Riot of 1906

Article about the Argenta Race Riot of 1906

Argenta Race Riot Article (Part 1)

Argenta Race Riot Article (Part 1)

Argenta Race Riot Article (Part 2)

Argenta Race Riot Article (Part 2)

Argenta Race Riot of 1906

aka: Lynching of Homer G. Blackman

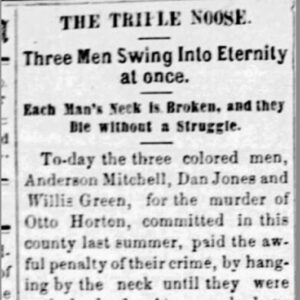

Arkadelphia Executions Article

Arkadelphia Executions Article