calsfoundation@cals.org

Methodists

Methodism came into what is now Arkansas at least two decades before statehood, just as it had been brought to North America at least two decades before the American Revolution. Led by John Wesley, an Anglican priest; his brother Charles; and a few others, Methodism had begun as a movement within the Church of England in the 1720s. Wesley never considered himself anything but an Anglican priest, but after the Americans had won their independence, his followers here demanded a new and separate church.

Structure of the Church

Wesley’s followers studied and worshiped as small independent classes or societies until the Methodist Episcopal (ME) Church in America was officially organized in Baltimore in 1784. At that time, the church had nearly 15,000 members.

The United Methodist Church today retains the structure Wesley created, adapting it from the Church of England in the eighteenth century. The ruling body of the church is the General Conference, which has met regularly since 1784 and today includes both clergy and lay delegates. The General Conference meets every four years to review the Discipline, the statement of beliefs of the church, to make changes or additions as needed.

Methodism kept pace with pioneers as they moved west, and geographical conferences were organized as the areas were settled. Each conference was governed by a body consisting of all the clergy members assigned within its geographical area; an equal number of lay members are now elected to each annual conference. The geographical conferences were sub-divided into districts, and each district was composed of circuits (many churches over a wide area), charges (two or three churches in a smaller area), and station churches (a single congregation). Preachers are assigned to each appointment by the bishop, with the advice and counsel of his or her cabinet, at each annual conference session. Each level of church organization meets annually to review its work; the Arkansas Conference now meets each June.

In 1940, the church added jurisdictional conferences, which are regional groups of conferences that meet once every four years and are responsible for electing and assigning bishops.

Early History of Methodism in Arkansas

Officially, Methodism came to what is now Arkansas around 1815, when the Tennessee Conference established the Spring River Circuit in its Arkansas District and began appointing preachers to ride it. The first was the Reverend William Stevenson, who resided in Bellview, Missouri. The circuit covered the area along the watersheds of the Little Red, Spring, Strawberry, and White rivers. Stevenson was assisted by young Eli Lindsey, a “local” preacher who lived near the present town of Jesup (Lawrence County). A local preacher was one who was ordained but did not accept appointments requiring him to move outside his home area. After one year, Lindsey reported “88 white members and 4 colored” on the circuit.

The first congregation known to have existed in Arkansas was probably the church at Flat Creek in western Lawrence County, dating from about 1815. It may have met for awhile in Lindsey’s home. The oldest church under continuous appointment today is the Washington United Methodist Church, founded in 1821 as a successor to the even older Henry’s Chapel near Ozan (Hempstead County). The Reverend John Henry Sr., who is said to have preached the first Methodist sermon in Little Rock (Pulaski County) as his party traveled toward their destination, led the congregation. The log chapel built at Ozan may have been the first Methodist church building in the state.

Arkansas became a state in 1836, and Arkansas Methodists were separated from the Missouri Conference into the Arkansas Conference that same year. The organizing conference, with the Reverend Burwell Lee presiding, was held in Batesville (Independence County) and recorded a membership of twenty-seven preachers. At least seven of these men were associated with Indian mission work. Some were Native Americans themselves; several had Native American wives. Indian mission work in the state and in neighboring Indian Nations remained a part of the Arkansas Conference until 1844.

Other Methodist Denominations

The Methodist Episcopal Church in America suffered its first schism in 1816, when a free Black man named Richard Allen led a group of African Americans in establishing the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in Philadelphia. A few years later, another Black Methodist denomination was founded, the African Methodist Episcopal, Zion (AMEZ). Both AME and AMEZ churches are still active in Arkansas. Shorter College in North Little Rock (Pulaski County), founded as Bethel Institute in 1886, is an institution of the AME Church.

Another distinct denomination separated from the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1830. A group of reformers, believing that the church was not democratic enough, had been agitating for change for over a decade. Among the features they adopted when they organized a new church four years later were equal representation for laymen (although not women) at the conference sessions and replacement of bishops by elected presidents. They also decided that committees at the annual conferences should appoint the preachers. As the Methodist Protestant Church, the new denomination remained separate until the Uniting Conference of 1939. By that time, the newly created Methodist Church embraced most of their reforms.

The most painful and damaging schism within the Methodist Episcopal Church, however, came about at the General Conference of 1844. The issue was slavery, which would divide the United States itself some seventeen years later. Out of a whirlwind of debate, and even violence, the various annual conferences in the slave-owning states of the South withdrew and formed a new denomination, calling it the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. Some ME or “Northern” churches struggled to survive in parts of northwestern and northern Arkansas, but most had closed by the late 1850s and reopened their doors only after the Civil War.

One other branch of Methodism that exists in Arkansas today developed after the Civil War. In 1870, freed slaves who had once attended the ME Church, South, with their masters were organized briefly into a separate conference and then into a separate church. This became the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church, now the Christian Methodist Episcopal (CME) Church.

African Americans continued to belong to the ME Church, although they usually had separate congregations. Some of these early Black ME churches are still active today, including Wesley Chapel in Little Rock, founded in 1853; Mount Olive in Van Buren (Crawford County), founded in 1869; and St. James in Fayetteville (Washington County), founded circa 1869. Philander Smith College was founded by the ME Church in Little Rock in 1877 as Walden Seminary and continues to thrive today as an institution of the United Methodist Church.

Formation of the United Methodist Church

The two Methodist Episcopal Churches, North and South, and the Methodist Protestant Church co-existed uncomfortably for almost a century. Finally, after many years of negotiations, the three denominations merged at the so-called Uniting Conference of 1939 to form one nationwide body known as the Methodist Church.

One other change in the national organization of the church had little impact on Arkansas. In 1968, the Methodist Church united with the former Evangelical United Brethren (EUB) Church, taking the current official name—the United Methodist Church. A congregation at Wye (Perry County) was the only EUB church in the state at that time.

Even after the merger of 1939, however, the Methodist Church remained racially segregated by annual conferences until 1972. The Southwest Conference, made up of Black congregations in Arkansas and Oklahoma, was the last segregated conference to disappear.

By the time of the 1939 merger, the Methodist Protestants had already begun to ordain women. Most served as associate pastors with their preacher husbands, but the Reverend Fern Cook, sent to the Hardy–Mammoth Spring charge in 1943, was the first woman to be given a regular appointment on her own. The Reverend Everne Hunter was the first woman to be ordained by the Methodist Church in Arkansas (1964). The Reverend Joyce Harris was the first Black woman to be ordained in the state (1980), and the Reverend Maxine Waller Allen was the first Black woman to be given an appointment when she was named chaplain at Philander Smith College in 1997.

Education, Social Service, and Other Ministries

Education and social service have historically been strong components of Methodism. Its Sunday schools in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century England often gave poor children their only opportunity to learn to read and write. In Arkansas, mission schools were established for Native American children in the 1830s in western Arkansas and in the Indian Nations.

Two Methodist-related institutions of higher learning now exist in the state—Hendrix College and Philander Smith College—but before public education became a reality in Arkansas, there were Methodist academies, seminaries, and district high schools for both boys and girls throughout the state. More than fifty such institutions existed, including the Washington Male and Female Seminary (established in 1846), Soulesbury Institute at Batesville (1849), Tulip Female Collegiate Seminary in Dallas County (1850), Quitman College (1870), the Dardanelle District High School (1873), and the Valley Springs School (1922).

The church also has one of the oldest denominational newspapers in the state. There were several failed attempts at newspaper publishing going back to the 1850s, but in 1882, the Reverend John W. Boswell expanded a small paper he had been publishing in Morrilton (Conway County), moved it to Little Rock, and renamed it the Arkansas Methodist. Now known as the Arkansas United Methodist, it is still published twice a month by the Arkansas Conference.

The temperance movement was an early focus of Methodist ministry. One of the earliest temperance societies in Arkansas was founded at Batesville in 1831, largely with Methodist participation, and Methodist preachers and lay members were in the forefront of such organizations as the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and the Anti-Saloon League. Modern-day United Methodists in Arkansas have added their opposition to organized gambling.

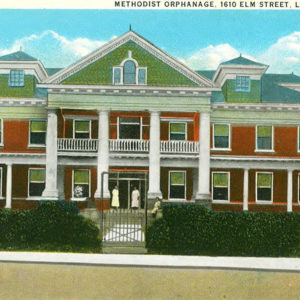

The ME Church, South, established an orphanage in Little Rock in 1902, which provides somewhat different services today as the United Methodist Children’s Home, a part of the Methodist Family Health System. In the beginning, the home provided food, shelter, and basic care for orphans; today, its services are mostly related to behavioral health, such as counseling for families and children, therapeutic care in foster care and group homes, and providing emergency shelter.

The first Methodist hospital in the state began as the Methodist Sanitarium in Hot Springs (Garland County) in 1908. During the 1950s, small community hospitals in Paragould (Greene County), Jonesboro (Craighead County), Mountain Home (Baxter County), and West Memphis (Crittenden County) came to be owned or sponsored by the Church; the largest of these, the Methodist Hospital in Jonesboro, was sold in 1995. Methodists in northern and eastern Arkansas also contributed to the founding and support of the Methodist Hospital in Memphis, now the Methodist Healthcare and LeBonheur Children’s Hospital. Because of the financial commitment to the Memphis institution, it was never feasible to build a major Methodist hospital in Arkansas.

Camping has been another important part of Methodist ministry. In the nineteenth century, when few congregations had actual sanctuaries, circuit-riding preachers often held services in brush arbors or rough board “tabernacles” erected near springs for fresh water. People came from miles around, staying in tents or in rough cabins for several days or weeks. Four permanent Methodist campgrounds are still in operation—Ebenezer in Howard County (1822), Salem near Benton in Saline County (1867), Davidson in Clark County (1884), and Ben Few in Dallas County (1898). Nearly every Methodist district in the state had some kind of summer camp for families and young people by the 1940s, and an active Church camping program continues today. Mount Eagle Christian Retreat Center in Stone County, on land purchased in 1970, has been developed into a focal point for Methodist outdoor ministry in the northern part of the state.

Camp Aldersgate in Little Rock has played an especially important role in Arkansas Methodist history. Opened in 1946 on an abandoned turkey farm, it was originally used to train church and community service workers of all races. Once a secluded site outside the city limits, it offered for many years the only place in the state where racially integrated activities could take place. Camp Aldersgate today focuses primarily on providing camping and outdoor activities for children and adults with disabilities.

The United Methodist Church in Twenty-First-Century Arkansas

The 2010 session of the Arkansas Annual Conference reported that 721 United Methodist churches served 138,000 members in the state; by 2020, there were 634 churches and 117,440 members. The membership is second in number only to the total of the various Baptist denominations throughout the state.

The Church still includes traditionally Black congregations, although integrated congregations are becoming more common. The number of Black United Methodist ministers in Arkansas has risen slowly because many have been lured away to churches in Texas, Kansas, or Missouri, where they find larger congregations and better salaries. Some Methodist churches in Arkansas now have racially integrated ministerial staffs; white pastors have been appointed to traditionally Black congregations, and Black pastors have been appointed to traditionally white congregations. The three predominantly Black Methodist churches—the AME, AMEZ, and CME—have remained separate from each other and from United Methodism. They follow Methodist doctrine and ritual, and all are represented on the World Methodist Council. Independent churches calling themselves Congregational Methodists or Wesleyan Methodists are also scattered throughout Arkansas.

Amid disagreements relating to LGBTQ+ members of the Church, including considerations surrounding marriage and ordination, plans began to be developed for the creation of a more conservative denomination, the Global Methodist Church, to serve as the umbrella organization for congregations adhering to a more traditional Methodist discipline; this organization formally launched on May 1, 2022. Central United Methodist Church in Fayetteville, the Arkansas Conference’s largest congregation, and First United Methodist Church in Jonesboro, the conference’s second-largest congregation, formally began the process of exiting the United Methodist denomination, with the Jonesboro church voting on July 31, 2022, to break away. On November 19, 2022, the Arkansas Annual Conference of the United Methodist Church voted to ratify disaffiliation agreements from thirty-five congregations. A special session of the conference in May 2023 approved the disaffiliation of sixty-seven of the state’s 564 congregations, making a total of more than 100 churches that had begun disaffiliation. On October 15, 2023, the conference allowed sixty-two more congregations to disaffiliate.

For additional information:

Alderson, Willis Brewer. “A History of Methodist Higher Education in Arkansas, 1836–1933.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, 1971.

Anderson, James A. A Centennial History of Arkansas Methodism. Benton, AR: L. B. White Printing Co., 1935.

Britton, Nancy. Two Centuries of Methodism in Arkansas. Little Rock: August House, 2000.

Clemons, James T., and Kelly L. Farr, eds. Crisis of Conscience: Arkansas Methodists and the Civil Rights Struggle. Little Rock: Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, 2007.

Jewell, Horace. History of Methodism in Arkansas. Little Rock: Press Printing Co., 1892. Online at http://archive.org/details/historyofmethodi00jewe (accessed April 25, 2022).

Lockwood, Frank E. “35 Methodist Churches Get Exit Approval.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, November 20, 2022, pp. 1A, 11A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2022/nov/20/35-methodist-churches-get-exit-approval/ (accessed November 21, 2022).

———. “67 Methodist Congregations Get OK to Exit.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, May 14, 2023, pp. 1A, 10A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/may/14/67-methodist-congregations-get-ok-to-exit/ (accessed May 15, 2023).

———. “Arkansas Methodists Weigh Disaffiliation.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, July 16, 2022, p. 5B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2022/jul/16/arkansas-methodists-weigh-disaffiliation/ (accessed July 18, 2022).

———. “Church Convenes on How to Divide.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, June 2, 2022, pp. 1A, 7A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2022/jun/02/arkansas-united-methodists-working-toward/ (accessed June 2, 2022).

———. “Day of Reckoning.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, August 6, 2022, pp. 4B, 5B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2022/aug/06/day-of-reckoning/ (accessed August 6, 2022).

———. “Largest Methodist Church in State Splits.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, March 7, 2023, pp. 1A, 6A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/mar/07/fayetteville-united-methodist-church-votes-to/ (accessed March 7, 2023).

———. “Leaner Times Ahead.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, June 24, 2023, pp. 4B, 5B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/jun/24/after-exit-of-more-than-100-churches-arkansas/ (accessed June 26, 2023).

———. “Methodists to Decide 67 Churches’ Exit.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, May 13, 2023, pp. 1B, 3B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/may/13/methodists-to-decide-67-churches-exit/ (accessed May 15, 2023).

———. “Methodist Church in Jonesboro OKs Split.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, August 1, 2022, pp. 1A, 2A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2022/aug/01/jonesboro-first-united-methodist-church-votes-to/ (accessed August 2, 2022).

———. “Methodists Defer Plan for Separation.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, June 3, 2022, pp. 1A, 7A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2022/jun/03/arkansas-methodists-defer-plan-that-would-ease/ (accessed June 3, 2022).

———. “Methodists Weigh Disaffiliation.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, August 13, 2022, pp. 1B, 3B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2022/aug/13/central-united-methodist-church-denominations/ (accessed August 15, 2022).

———. “State’s Conference Lets 62 More Leave United Methodists.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, October 16, 2023, pp. 1A, 5A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/oct/16/states-conference-lets-62-more-leave-united/ (accessed October 16, 2023).

———. “United Methodists Take Look at Options.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, May 31, 2022, pp. 1A, 4A. Online at https://www.nwaonline.com/news/2022/may/31/arkansas-conference-of-the-united-methodist/ (accessed May 31, 2022).

Pyszka, Kimberly, Bobby R. Braly, and Jamie Brandon. “The Methodist ‘Manse’ of Cane Hill, Arkansas: A New History.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 77 (Autumn 2018): 250–265.

United Methodist Archives. Bailey Library. Hendrix College, Conway, Arkansas.

Vernon, Walter. Methodism in Arkansas, 1816–1976. Little Rock: Joint Commission for the History of Arkansas Methodism, 1976.

Nancy Britton

Arkansas United Methodist Historical Society

Emmet United Methodist Church

Emmet United Methodist Church Religion

Religion Arkadelphia Methodist College

Arkadelphia Methodist College  Sarah Esther Case

Sarah Esther Case  Dalark Church

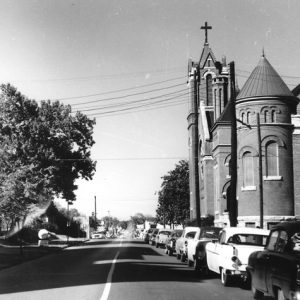

Dalark Church  First United Methodist Church

First United Methodist Church  First United Methodist Church

First United Methodist Church  Janice Huie

Janice Huie  Andrew Hunter

Andrew Hunter  Jasper Methodist Church

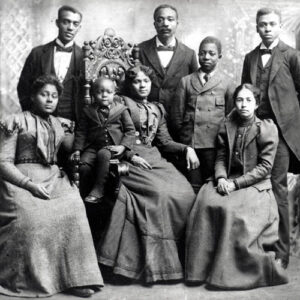

Jasper Methodist Church  Methodist Missionaries

Methodist Missionaries  Methodist Orphanage

Methodist Orphanage  Philander Smith College

Philander Smith College  Piggott Methodist

Piggott Methodist  Rockport Methodist Church

Rockport Methodist Church  Smyrna Methodist Church

Smyrna Methodist Church  Three Creeks Methodist Church

Three Creeks Methodist Church  Wesley Chapel United Methodist Church

Wesley Chapel United Methodist Church

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.