calsfoundation@cals.org

Wineries

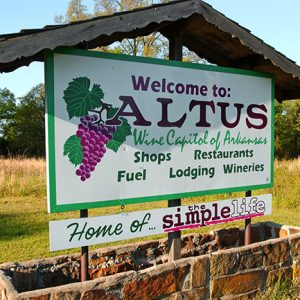

Winemaking in Arkansas began when European Catholics, primarily German-Swiss but also Italian, immigrated to the state, attracted by the range of opportunities the then-frontier had in store. Chances are that wine was made at the Hinderliter Grog Shop in Little Rock (Pulaski County), built around 1827 by Jesse Hinderliter, a man of German descent, and currently the oldest standing building in the city. In addition, there are accounts of a winery run by one J. Ressor about six miles south of Batesville (Independence County) in the 1830s and records of German immigrants in the small town of Hermannsburg (Washington County) making wine as early as 1845. However, the wine industry of Arkansas really took root in the 1870s. At that time, the Little Rock & Fort Smith (LR&FS) Railroad Company was building a line between Little Rock and Fort Smith (Sebastian County). The company advertised in Europe for workers, adding as an incentive a large tract of land for the building of a church. German-speaking Swiss immigrants were drawn to the area and soon settled in western Arkansas, establishing, most notably, the town of Altus (Franklin County), which remains the unofficial capital of Arkansas viticulture. Subiaco Abbey, a Benedictine monastic community founded in Logan County upon land also obtained by the railroad company, continued to draw German-speaking Catholics to the area.

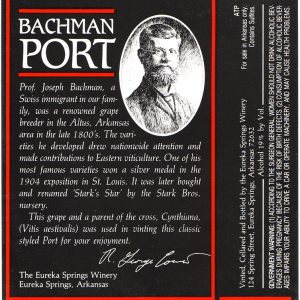

These immigrants, who brought with them a profound knowledge of grape growing and winemaking, easily adapted their skills to a climate and geography rather similar to what they had left behind. The two largest wineries in the state, Post Familie and Wiederkehr, originated in this period of immigration. Though many early wines were crafted from grapes and berries native to Arkansas, it did not take long for Arkansas’s grape growers to begin cultivating their own varieties. A luminary in this field was Joseph Bachman (1853–1928), a Swiss immigrant who developed the Sunrise, Stark’s Star, Banner, and Hubbard cultivars, among others. He earned national and international acclaim, including a silver medal in the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, Missouri, and the 1913 Wilder Award (often called the “Nobel Prize in fruit”).

Italian immigrants also played a major role in the state’s winemaking heritage. Austin Corbin, who owned and operated Sunnyside Plantation in Chicot County in the southeastern corner of the state, arranged in 1895 for Italian farmers and their families to immigrate and work for him at Sunnyside. Three years after their arrival, however, the combination of a severe malaria epidemic and dissatisfaction with their contracts and living conditions prompted them to leave Sunnyside. Led by Father Pietro Bandini, they settled in northwest Arkansas, founding the town of Tontitown (Washington County). The area’s soil was perfect for the cultivation of wine and juice grapes, especially Concord grapes. In 1899, the community held its first Tontitown Grape Festival, a tradition that continues to this day.

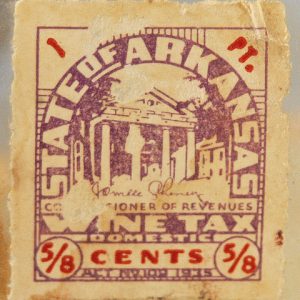

When Prohibition began in 1920, Arkansas wineries continued to make sacramental wine (used in Catholic and Jewish worship), which was still legal, and marketed grapes and grape juice. Many wineries went underground, selling their product clandestinely. When Prohibition finally came to an end in 1933, the Arkansas wine industry went through a renaissance that would last for approximately the next thirty years, with wineries emerging all across the state. Labels such as Lone Wolf, Big Bear, Eight Ball, and Dixie Dew became commonplace. The Ozarks, the Ouchitas, and Crowley’s Ridge proved to be the most popular locales for wineries, though more than thirty sprang up in southern Arkansas as well. Much of the wine from these emerging wineries was of questionable quality, especially during World War II, when the rationing of sugar meant there was not enough to make the sweeter wines most people enjoyed.

There have been over 150 bonded wineries in the state, but only a few remain today. The decline had several causes. First, many families had begun making wine only as a means of supplementing their farming incomes. It proved easy to abandon, especially when younger generations left the farm for jobs and education. Second, the emergence of dry counties killed many wineries. For example, the James Winery just outside of Jonesboro (Craighead County) went under when Craighead County voted to forbid the sale and production of alcohol. Third, the state’s ever increasing “sin tax” upon alcoholic beverages made it difficult for many to eke out a profit.

Post Familie and Wiederkehr are the largest wineries in the state and consistently rank among the top 100 in the nation in terms of gallons produced. Mount Bethel Winery was founded in Altus by Eugene and Peggy Post in 1956, though its roots stretch back to German and Swiss settlers. Cowie Wine Cellars, located outside of Paris (Logan County), was also the home of the award-winning Arkansas Historic Wine Museum. Chateau Aux Arc opened in Altus in the spring of 1998. The Winery in Hot Springs (Garland County) opened in 2006 and features a branch of the Arkansas Historic Wine Museum, and Keels Creek Winery in Eureka Springs (Carroll County) began production in 2006.

Tontitown Winery opened on October 15, 2010, marking the first time since the 1980s that a winery operated in that city. Movie House Winery in Morrilton (Conway County) opened in 2011, and Railway Winery & Vineyards near Eureka Springs opened in 2012 and produces native, hybrid, and fruit wines. In 2014, winemaking officially returned to Little Italy (Pulaski and Perry counties) when An Enchanting Evening, a local bed and breakfast and wedding venue, opened a licensed winery, and Bo Brook Farms near Roland (Pulaski County) also began offering wines produced from fruits grown on the farm.

In addition to crafting a number of familiar varietals of foreign origin, most of these wineries make wine from native grapes, such as the Cynthiana and the muscadine.

Around the beginning of the twenty-first century, Arkansas’s wine industry began undergoing something of a second renaissance, due in part to an attitude shift on the part of the state government, which has not always been friendly toward winemakers. In the fall of 2001, the Arkansas Alcoholic Beverage Control Board repealed its 1981 ban on the sale of native wine in grocery and convenience stores, allowing the industry thousands more venues for its products. These were exclusive venues, too, given that only state wines were allowed to be sold in such stores, and this development was especially fruitful for Post Familie and Wiederkehr, which saw their in-state sales skyrocket. Such limitations were later challenged successfully in court. In 2007, a late spring frost damaged much of the state’s grape crop. The opening of new wineries following the devastating frost speaks to the recovery of the industry. However, the state later opened up grocery and convenience store sells to out-of-state wineries, and though these originally could only be smaller operations, on March 15, 2017, Governor Asa Hutchinson signed a bill opening up such sales to wineries of all sizes.

In 2020, the University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture developed the Arkansas Quality Wine Program to advance the quality of grape and wine characteristics in the state.

For additional information:

Cook, Marty. “State Wineries Recovering from Dry Months.” Arkansas Business, August 17–23, 2020, pp. 10–11.

Cureau, Natacha. “Phylogenetic Diversity of Arkansas Vineyard and Wine Microbiota.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2020. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/3600/ (accessed July 6, 2022).

Fleming, Amanda. “Investigating Quality Attributes and Wine Production Methods of Arkansas-Grown Grapes.” MS thesis, University of Arkansas, 2022. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/4713/ (accessed March 20, 2023).

Frago, Charlie. “Wineries Seek Help to Crush Problem.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. December 14, 2008, pp. 1B, 2B.

Gettinger, Aaron. “Vintners Adjust to Changing Weather.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, October 19, 2023, 1D, 2D. Online at https://www.nwaonline.com/news/2023/oct/19/altus-winegrowers-see-climate-change-affecting/ (accessed October 23, 2023).

Harding, Julia, Jancis Robinson, and Tara Q. Thomas, eds. The Oxford Companion to Wine. 5th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2023.

Harris, Matt. “State Wineries Hanging Tough.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. August 9, 2009, pp. 1G, 2G.

Henry, Patrick. “Arkansas Wine Industry Withers while Grapes Thrive.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. November 28, 1998, p. 1B.

Johnson, Ben F. John Barleycorn Must Die: The War against Drink in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2005.

Mayfield, Sarah. “Techniques to Enhance the Attributes of Wines Produced from Grapes Grown in Arkansas.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2020. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/3609/ (accessed July 6, 2022).

Noguera, Emilio. “Economics of Wine and Grape Juice Production in Arkansas.” MS thesis, University of Arkansas, 2003.

Reed, Jennifer Barnett. “Ripe on the Vine.” Arkansas Life, October 2011, pp. 34–39.

Schnedler, Marcia. “Sampling Arkansas’ Wine Country.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. July 21, 1996, 2H.

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Agriculture

Agriculture American Viticultural Areas

American Viticultural Areas American Wine Society - Arkansas Chapter

American Wine Society - Arkansas Chapter Blue Laws

Blue Laws Breweries

Breweries Wiederkehr Weinfest

Wiederkehr Weinfest Altus Wineries Sign

Altus Wineries Sign  Altus Grape Festival Grape Stomping

Altus Grape Festival Grape Stomping  Arkansas Historic Wine Museum

Arkansas Historic Wine Museum  Arkansas Wine Tax Stamp

Arkansas Wine Tax Stamp  Bachman Port

Bachman Port  Bear Cat Wine

Bear Cat Wine  Belotti Vineyards

Belotti Vineyards  Chateau Aux Arc Vineyards and Winery

Chateau Aux Arc Vineyards and Winery  Chateau Aux Arc Vineyards and Winery

Chateau Aux Arc Vineyards and Winery  Cowie Wine Cellars

Cowie Wine Cellars  Granata Winery

Granata Winery  Grape Bins

Grape Bins  Harvesting Grapes

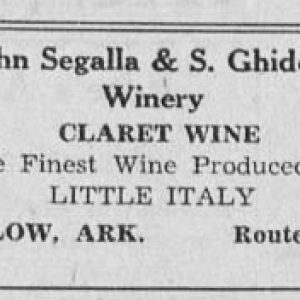

Harvesting Grapes  John Segalla Winery

John Segalla Winery  Mount Bethel Winery

Mount Bethel Winery  Muscadine Grapes

Muscadine Grapes  Peggy Earl Winery

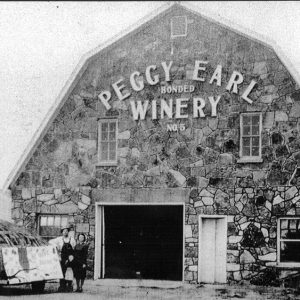

Peggy Earl Winery  Point Remove Brewing Company Products

Point Remove Brewing Company Products  Post Familie Vineyards and Winery

Post Familie Vineyards and Winery  Post Familie Winery Bottle

Post Familie Winery Bottle  Vinola Winery

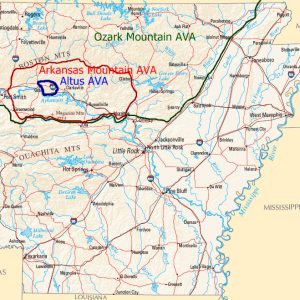

Vinola Winery  Viticultural Areas Map

Viticultural Areas Map  Wiederkehr Wine Cellars

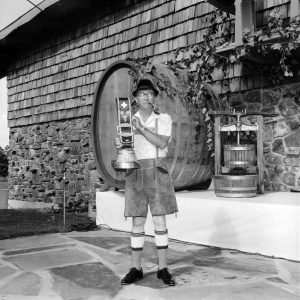

Wiederkehr Wine Cellars  Herman Wiederkehr

Herman Wiederkehr  Winery Ad

Winery Ad

From: http://www.eclecticatbest.com/2016/04/the-swiss-vintner-prohibitionist-mayor.html No information can be found on when Loetscher started growing grapes and making wine. In any case, he was among the first farmers in the state to do so. According to the EOA, the earliest vintners in Arkansas included Johann Wiederkehr, from Switzerland, and Jacob Post, from Germany, both of whom both produced wines in Altus (Franklin County). Both started making their wines in about 1880. Apparently by 1888, several German-speaking farmers in Central Arkansas were growing grapes and selling wine made from them. An article in the Daily Arkansas Gazette promoting life in Faulkner County mentioned grape growing and wine production: Grape culture is receiving a great deal of attention, the Concord and other varieties yield immense quantities of wine (400 to 500 gallons per acre) and sells for $1 and upwards per gallon. The German citizens (always thrifty and prosperous wherever they may be) are developing this industry very rapidly. Not long after this article was published, after the sale of locally made wine was prohibited within three miles of the Conway public school, commercial wine making in Conway came to a quick end. According to the Echo, as more Germans settled in Conway in the 1870/80s, Loetscher provided them advice and help: He was long valued as an authority on many things, especially on the topic of wine making. He had established a splendid wine garden and lived happily and contentedly in his own way with his family, until the College was built here.