calsfoundation@cals.org

USPHS Venereal Disease Clinic

In 1921, Hot Springs (Garland County) became home to the first federally run venereal disease (VD) clinic in American history. Established by the United States Public Health Service (USPHS or PHS) after World War I, the clinic (which was located on Spring Street) constituted one part of a broader federal campaign against syphilis and gonorrhea—diseases considered to be on the rise across the country. Hoping to stem the tide of the “venereal peril,” governmental officials envisioned the clinic as a research facility whose personnel would devise and disseminate new, improved methods for diagnosing and treating VD. Given its long-standing reputation as a therapeutic haven for those infected with syphilis, Hot Springs seemed an obvious headquarters for such a project.

From 1921 through 1936, the clinic’s director was Oliver C. Wenger, a venereologist with the PHS Division of Venereal Diseases. Upon arriving in Hot Springs, Wenger embarked on a rather traditional VD control campaign—tracking down the sexual contacts of those who entered the clinic, experimenting with novel drugs and curative technologies, and cracking down on the city’s brothels. As this last aspect of his early work indicates, Wenger’s understanding of VD was highly moralistic. In addition to labeling prostitutes “uncontrolled spreaders of infection” and “a menace to the community,” Wenger gave lectures within the clinic that stressed personal responsibility: patients were informed that their illnesses were a result of their own misconduct, and that recovery was a matter of individual choice.

With the passage of time, however, the clinic’s response to VD evolved considerably. Continually encountering patients whose struggles left them both incapacitated and impoverished, Wenger began to view people with VD in a much more sympathetic light. The onset of the Great Depression only strengthened this new interpretation of the country’s VD troubles. Arguing that America’s inability to solve these problems reflected not faulty morals but “faults in our economic structure,” Wenger lobbied for funds to provide free room and board to the clinic’s patients. In 1933, he secured this, as the newly created Federal Transient Bureau (FTB) began providing shelter, clothing, food, and medical attention to all clinic patients. The following year, the bureau built a transient center on the outskirts of the city for the clinic’s unmarried white male patients. Known as Camp Garraday, this facility boasted nine barracks, a sixty-bed infirmary, a kitchen, a dining hall, and a recreation building. Taken together, these measures dramatically increased the number of patients leaving Hot Springs in a non-infectious state.

Despite this improvement, there were limits to the PHS’s increasingly economically focused campaign against VD, particularly in regards to African American patients. As Camp Garraday illustrates, the federal government cared more about the health of white men than that of women and racial minorities. While thousands of African Americans received treatment at the clinic, they experienced exceptional hardships here. Most arrived later in the course of their infections and left much earlier than their white counterparts. In part, these discrepancies reflected the economic effects of racial segregation. As a city steeped in the values of the Jim Crow South, Hot Springs barred Black visitors from all but a few of its private bath houses and hotels. Individual acts of racism also played a role. On one occasion, a Black man was expelled from the clinic after becoming “impudent”; on another, a Black man was discharged after doctors alleged that he had been “peeping into the window of the female gynecologic douche room.” Moreover, while Wenger and his staff sometimes dipped into their personal savings to reduce white patients’ expenses, it does not appear that this financial largesse was ever extended to Black patients. Employing a eugenic mindset, Wenger believed that the clinic’s ultimate purpose was “race conservation”—in other words, the rehabilitation of diseased white bodies; improving Black health was not a priority. Thus, though the FTB’s efforts helped somewhat, the racial health gap persisted: a 1940 study revealed that whereas the average white patient received twelve injections of Salvarsan, the average Black patient received only nine.

By this point in time, the clinic’s importance had begun to decline. After the passage of the National VD Control Act in 1937, states dramatically expanded their anti-venereal infrastructures. In that year, Arkansas had no state-run VD clinics; by 1943, it had eighty-three. The arrival and subsequent dissemination of penicillin in the mid-1940s also spurred a precipitous decline in the number of individuals traveling to Hot Springs for anti-syphilitic treatment. In 1948, the PHS clinic officially closed, and although rates of syphilis and gonorrhea rose in subsequent decades, Hot Springs played no part in postwar developments in combatting these diseases.

For additional information:

Bowen, Elliott G. In Search of Sexual Health: Diagnosing and Treating Syphilis in Hot Springs, Arkansas, 1890–1940. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2020.

Percefull, Janis Kent. “The USPHS Venereal Disease Clinic at Hot Springs, Arkansas: Director O. C. Wenger’s Legal Angle.” The Record 45 (2004): 32–51.

Reichard, Victoria. “A Widespread and Devastating Problem: The Hidden History of Camp Garraday in World War II Hot Springs.” The Record 62 (2021): 11.1–11.18.

Elliott G. Bowen

Nazarbayev University

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Health and Medicine

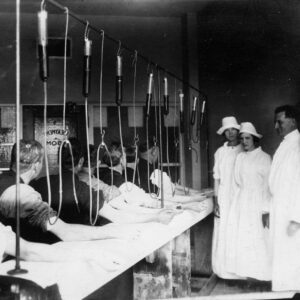

Health and Medicine USPHS Clinic's Salvarsan Room

USPHS Clinic's Salvarsan Room  USPHS Venereal Disease Clinic

USPHS Venereal Disease Clinic  USPHS's Camp Garraday Clinic

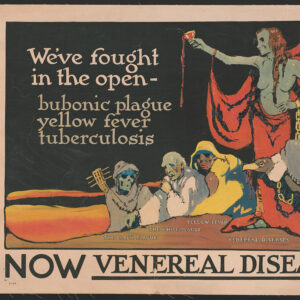

USPHS's Camp Garraday Clinic  VD Poster

VD Poster

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.