calsfoundation@cals.org

Segregation and Desegregation

aka: Integration

Segregation and desegregation in Arkansas cannot be understood using the same model that has defined these matters in other Southern states. Throughout the state, the pace at which segregation occurred varied. The ways in which Jim Crow laws were manifested in Arkansas differed and were dependent largely upon the area of the state, the proportion of Black residents to white residents, and whether or not those individuals lived in rural or urban settings. The extent to which African Americans were willing to acquiesce to customary or legalized segregation also varied according to the part of the state, as class differences often limited the effectiveness of civil rights initiatives. The story of desegregation in Arkansas tells of many failures, some victories, and even regression as the journey from segregation to desegregation witnessed many pitfalls in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

The earliest state-mandated segregation in Arkansas occurred with the passage of Act 52 of 1868, which established segregated education for Black and white students. The quandary in which most Black citizens found themselves required them to consider which would be the lesser of two evils: exclusion or segregation. Rather than be marginalized entirely, at least when it came to education, they chose separate albeit inferior educational facilities. The ways in which Black Arkansans responded to segregation varied from place to place in the state. For the Black middle class, resistance to segregation often came in the form of enhanced dedication to economic independence and community self-sufficiency even as it fought for first-class citizenship. For those who were less fortunate, de jure (by law) segregation, rural labor, and—if female—domestic service characterized the depraved standard of living to which they were subjected.

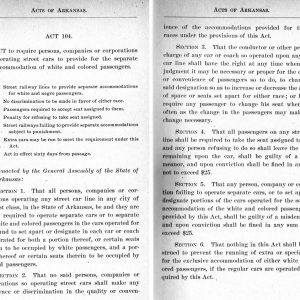

As was the case in other Southern states, Arkansas wasted little time in approving measures to disfranchise Black citizens at the end of the nineteenth century. Using the “white primary” rule, the Democratic Party managed to effectively eliminate the Black vote. Such actions set the stage for legislation to ensure that Black citizens were marginalized in mainstream life in Arkansas, a process that occurred most rapidly in urban areas. Segregation statutes deliberately designed to mark Blacks as an inferior caste were not actually codified in law until the Separate Coach Law of 1891. What followed was a series of laws requiring the separation of Blacks and whites in virtually every aspect of life. These laws included separate Black and white state prisons and restrictions on miscegenation that defined African Americans by the “one-drop rule.” The Streetcar Segregation Act of 1903 resulted in a Black boycott in several Arkansas cities.

Although racial discrimination was a pervasive part of daily life for Black Arkansans, its application was often arbitrary. In Little Rock (Pulaski County), for example, Blacks and whites continued to frequent the same saloons and restaurants as late as the 1890s. In 1892, a concert at Glenwood Park had an integrated audience, and the public springs of Searcy (White County) were utilized by Black and white citizens until the late nineteenth century. While segregation may have placed some limitations on Blacks’ activity, it also provided opportunities for those who were educated and ambitious, and allowed for the creation of a Black middle class.

For Black residents of urban areas like Little Rock, the inconvenience of arbitrary racial proscriptions did not blind them to economic and professional opportunities. Whatever tension local whites may have felt because of their presence, by the last two decades of the century, there was a small but independent class of Black artisans, craftsmen, and other professionals. Racial segregation also meant that Blacks were able to take advantage of educational opportunities, and Black teachers were assured of jobs in Black schools. An act passed in 1871 provided for separate but equal school systems, and it also required the training of Black faculty to teach in them; this teacher-training void was filled with the opening of the Branch Normal College (now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff) in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) in 1873. Philander Smith College, formerly known as Walden Seminary, which provided access to higher education for Black Arkansans, was founded in 1877.

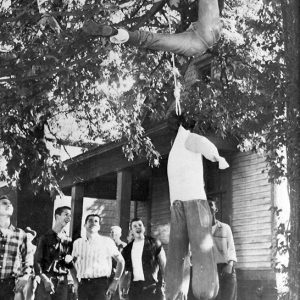

Unfortunately, along with these marginal successes came great danger. In the 1890s, in Arkansas and throughout the South, mob violence directed at African Americans increased substantially as whites produced restrictive means to relegate them to second-class status. Such violence particularly meant the lynching of Black men for allegedly raping white women or overstepping acceptable racial boundaries. The sheer barbarism of racial violence along with rapidly disappearing socioeconomic opportunities left Black citizens discouraged, disillusioned, and vulnerable. Although many found themselves trapped in the quagmire of the exploitative sharecropping or tenant farming system, others embraced the “back to Africa” movement or left the South with thousands of others and migrated to northern or western locales.

Such was the state of affairs for Black Arkansans at the turn of the century as the situation went from bad to worse and as white Arkansans intensified their efforts to exclude African Americans from state politics. As the Democratic Party closed in on political offices throughout the South, so too was the case in Arkansas. In 1890, the Populist Party still remained firmly entrenched in Arkansas politics—a position that the Democratic Party found increasingly threatening. Their concerns were not unfounded. Black farmers found the movement appealing as well and, by 1885, had organized local alliances into the Sons of the Agricultural Star. By 1888, it had been absorbed into the larger and formerly all-white Agricultural Wheel and Brothers of Freedom. With the threat of a biracial alliance looming, white Democrats in Arkansas followed the example of Mississippi, its neighbor to the east, and began considering the exclusion of Black votes. Although Black citizens had clung to the Republican Party as the “Party of Lincoln” and its best chance at first-class citizenship, even the Republican Party had begun to go the way of white supremacy and thus disconnected itself from the primacy of the Black vote. By the end of the nineteenth century, the “lily-white” Republican movement and disfranchisement successes of the Democratic Party left African Americans politically prostrated in Arkansas. Unfortunately, this was merely the beginning of a series of affronts as Blacks scrambled to find a safe haven in a rapidly changing, virulently racist society.

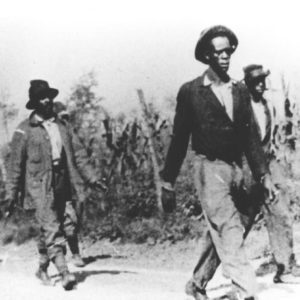

As in most locales in and around the South, the World War I years witnessed the mass migration of African Americans out of Arkansas in order to escape racism and the lack of economic opportunities. Many however, chose to stay and fight to make their home state a more equitable place to live. Their failure to do so was revealed in the Elaine Race Massacre in 1919 when Blacks, some whom had founded the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America to protest the ill treatment of farmers, were hunted down and killed by local whites who had assumed that they were planning an insurrection.

By the 1920s, in addition to the laws mandating separate educational institutions, Arkansas also had seven laws requiring the physical segregation of the races. Because of the relatively small number of Blacks in Arkansas compared to those in the Deep South, Jim Crow segregation was far less onerous. Relationships across the racial divide remained relatively fluid; relations between Blacks and whites often varied by class and location. Some Little Rock neighborhoods, for example, continued to enjoy integrated housing.

Despite this, Black citizens waged a long fight against Jim Crow segregation in Arkansas. In the 1930s, Blacks did not fare much better than they had in previous decades. Even in the depths of the Great Depression and despite government assistance, Blacks still faced racial injustices. In Little Rock, for example, African Americans made up twenty percent of the population but represented fifty-four percent of the unemployed. Many Blacks also found themselves on the relief rolls, although they received disproportionately less benefits than white families. Black Arkansans fared little better in gaining employment on New Deal projects. When opportunities were available on Works Progress Administration (WPA) programs, Black applicants were seldom hired because local whites thought the pay was above what they ought to receive. White Arkansans also perceived New Deal programs as challenges to the Southern racial status quo. As such, they reacted viscerally to its programs and any form of progress they offered. Such was the case for Blacks when it came to the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA). Discrimination in New Deal programs worsened already dire circumstances for Black Arkansans. The AAA’s crop reduction program led to the eviction of impoverished, overwhelmingly Black sharecroppers. The Social Security Act excluded maids and farm workers, leaving them with no form of social insurance.

Although small steps for racial justice were evident even in the years of the Great Depression and the New Deal, it was World War II that propelled Blacks to push for at least making the “but equal” part of “separate but equal” a reality in Arkansas. In the 1940s, as the United States entered World War II, Black citizens were increasingly unwilling to accept second-class citizenship in Arkansas, noting the hypocrisy of fighting a war for democracy while being denied it in the land of their birth. As military bases were created in Arkansas, the state’s economy rebounded from the Depression years. This was a tremendous boon to African Americans, who moved to urban areas to procure jobs in wartime industries. But these years also provided Black Arkansans with a renewed impetus to challenge racial discrimination and legalized segregation. As more than eighty percent of Black soldiers were trained on Southern military bases, those from Northern states were particularly galled by the overt racism and segregation they found there. As Southern whites became increasingly alarmed by the presence and assertiveness of Black soldiers, Jim Crow restrictions were enforced more aggressively, and the tensions between the races increased.

In Arkansas, such civil rights organizations as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) continued its activism as new organizations formed. In 1940, Black leaders in the state formed a new organization, the Committee for Consideration of Educational Problems of Negroes. Recognizing that separate education clearly did not mean equal education in Arkansas, Black leaders recommended improvements in Black schools and improved economic opportunities. However, they were cautious not to demand an end to the system of segregation itself. It was not until the 1950s that demands for desegregation intensified. Such activism most notably involved desegregating public schools and institutions of higher learning throughout Arkansas.

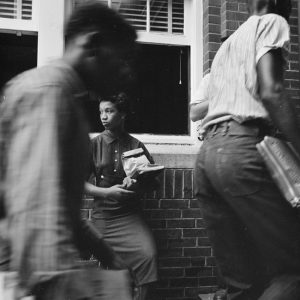

Although the desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock in 1957 and the story of the Little Rock Nine are well known and documented in the state’s history, some educational facilities in Arkansas had been desegregated earlier. In 1946, the Lower Whorton Creek School in rural Madison County had secretly enrolled a Black pupil, Laverne Cook, despite state laws mandating segregation, due in part to the fact that she was the only school-age African-American child in the county, and arranging a segregated learning space would have been costly. The first Black student to desegregate an institution of higher education in the post-Reconstruction South was Silas Hunt, who enrolled at the University of Arkansas School of Law in 1948. As for the state’s public schools, Charleston (Franklin County) schools were the first in the former Confederacy officially to desegregate following the U.S. Supreme Court decision of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, followed soon thereafter by Fayetteville (Washington County) schools, whose school board was actually the first to approve desegregation.

Throughout Arkansas, particularly in areas with sparse Black populations such as Van Buren (Crawford County), Fort Smith (Sebastian County), Bentonville (Benton County), and Hot Springs (Garland County), schools desegregated with barely a second glance from its citizens. It was only in Hoxie (Lawrence County) in 1955, after the school board unanimously concluded that integration was “morally right in the sight of God,” that some local whites became angry and threatened to boycott the schools. In Little Rock, the open defiance of desegregation in public schools was obvious. Only 16.7 percent of Black students attended integrated schools by the mid-1960s. By 1976, Black students constituted the majority of the Little Rock public school population. In the 1980s, the figure was at about seventy percent as white parents fled to surrounding suburban communities. Desegregation did not lead to full integration.

Desegregation efforts in Arkansas were not limited to schools. In the 1960s, Black students from Philander Smith College attempted to desegregate the Woolworth’s lunch counter in downtown Little Rock. They succeeded in 1963. Unfortunately, like segregation in the late nineteenth century, desegregation also occurred at varying rates statewide. As in most Southern states, desegregation and recognition of first-class citizenship for all people in Arkansas was an arduous and painful process.

For additional information:

Adams, Julianne Lewis, and Tom DeBlack. Civil Obedience: An Oral History of School Desegregation in Fayetteville, Arkansas, 1954–1965. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994.

Bell-Toliver, LaVerne, ed. The First Twenty-Five: An Oral History of the Desegregation of Little Rock’s Public Junior High Schools. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2018.

Bowden, Bill. “In ’46, White School Enrolled Black Girl.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, February 3, 2019, pp. 1A, 8A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2019/feb/04/in-46-white-school-enrolled-black-girl-/ (accessed March 2, 2023).

Clausen, Tammie. “A Successful Merger: The Integration of the Tuckerman School District.” The Stream of History 53 (2020): 78–89.

Cohen, Rachel M. “School Choice and the Chaotic State of Racial Desegregation.” American Prospect, September 15, 2015. Online at https://prospect.org/education/school-choice-chaotic-state-racial-desegregation/ (accessed March 21, 2023).

Cope, Graeme. “‘A Mockery for Education’? Little Rock’s Thomas J. Raney High School during the Lost Year, 1958–1959.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 78 (Autumn 2019): 248–273.

———. “‘Something Would Develop to Prevent It’: North Little Rock and School Desegregation, 1954–1957.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 74 (Summer 2015): 109–129.

Corrigan, Lisa M. “The (Re)segregation Crisis Continues: Little Rock Central High at Sixty.” Southern Communication Journal 83.2 (2018): 65–74.

Gordon, Fon Louise. Caste and Class: The Black Experience in Arkansas, 1880–1920. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1995.

Graves, John William. Town and Country: Race Relations and Urban Development in Arkansas, 1865–1905. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1990.

Harris, Adam. “An Attempt to Resegregate Little Rock, of All Places.” The Atlantic, October 22, 2019. https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2019/10/little-rock-still-fighting-school-integration/600436/ (accessed October 22, 2021).

Hosken, Simon. “Policing the Blues: Remembering the Desegregation of Law Enforcement in West Memphis, Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 72 (Summer 2013): 120–138.

Johnson III, Ben F. Arkansas in Modern America since 1930. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2019.

Kilpatrick, Judith. “Desegregating the University of Arkansas School of Law: Clifford Davis and the Six Pioneers.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 68 (Summer 2009): 123–156.

Kirk, John A. “Capitol Offenses: Desegregating the Seat of Arkansas Government, 1964–1965.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 72 (Summer 2013): 95–119.

———. “Going off the Deep End: The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Desegregation of Little Rock’s Public Swimming Pools.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 73 (Summer 2014): 138–163.

———. “Not Quite Black and White: School Desegregation in Arkansas, 1954–1966.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 70 (August 2011): 225–257.

———. Redefining the Color Line: Black Activism in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1940–1970. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2002.

———. “Swimming against the Tide of Desegregation in Little Rock.” Arkansas Times, February 6, 2014, pp. 12–17. Online at http://www.arktimes.com/arkansas/swimming-against-the-tide-of-desegregation-in-little-rock/Content?oid=3199765 (accessed October 22, 2021).

Kirk, John A., Kathleen Burrell, Brittany Fugate, Christy Hendricks, Ellis Eugene Thompson, Michael White, Logan H. Yancey. “Criminal Justice in the Age of Segregation: The Arkansas Cases of Robert Bell and Grady Swain.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 81 (Spring 2022): 19–45.

Lackey, Joseph. “On the Doorstep of Oak Forest: Blockbusting and a Residential Response.” Pulaski County Historical Review 64 (Fall 2016): 96–95.

Landers, Misty. “Just Discrimination: Arkansas Parochial Schools and the Defense of Segregation.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2017. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2407/ (accessed July 6, 2022).

Newman, Mark. “The Arkansas Baptist State Convention and Desegregation.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 56 (Autumn 1997): 294–313.

———. “The Catholic Church in Arkansas and Desegregation, 1946–1988.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 66 (Autumn 2007): 293–319.

———. Desegregating Dixie: The Catholic Church in the South and Desegregation, 1945–1992. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2018.

Office of Desegregation Monitoring Records. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Patton, Adell Jr. “Surviving the System: Pioneering Principals in a Segregated School, Lincoln High School, Forrest City, Arkansas.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 42 (April 2011): 3–21.

Price, Polly J. “The Little Rock School Desegregation Cases in Richard Arnold’s Court.” Arkansas Law Review 58.3 (2005): 611–662.

Ramsey, Patsy. “Crossing Boundaries: Racial Desegregation of Arkansas Public Higher Education.” EdD diss., University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 2009.

“The Road from Hell Is Paved with Little Rocks.” University of Arkansas at Little Rock Virtual Exhibit. https://ualrexhibits.org/desegregation/ (accessed October 22, 2021).

Semuels, Alana. “How Segregation Has Persisted in Little Rock.” The Atlantic, April 2016. http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2016/04/segregation-persists-little-rock/479538/ (accessed October 22, 2021).

Stephan, Stephan A. “Desegregation of Higher Education in Arkansas.” Journal of Negro Education 27 (Summer 1958): 243–252.

Stewart, Jeffrey. “The Integration of the Pulaski County Special School District, 1954–1965.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 78 (Summer 2019): 111–139.

———. “Public School Desegregation and Private Schools: A Case Study of Central Arkansas Christian School.” Pulaski County Historical Review 62 (Spring 2014): 2–15.

Tell-Hall, Nancy. “An ODD Story: The Desegregation of Fisher’s Bar-B-Q in Little Rock, Arkansas.” Pulaski County Historical Review 66 (Spring 2018): 19–26.

“The Integration of Hoxie: A Panel Discussion.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 35 (December 2004): 188–203.

Wood, Hannah. “A College Struggles: Harding College’s Journey toward Integration.” White County Heritage 59 (2021): 53–57.

Cherisse Jones-Branch

Arkansas State University

Arkansas State Capitol, Desegregation of the

Arkansas State Capitol, Desegregation of the Bentonville Schools, Desegregation of

Bentonville Schools, Desegregation of Central High School, Desegregation of

Central High School, Desegregation of Charleston Schools, Desegregation of

Charleston Schools, Desegregation of Hoxie Schools, Desegregation of

Hoxie Schools, Desegregation of Van Buren Schools, Desegregation of

Van Buren Schools, Desegregation of Dick Allen

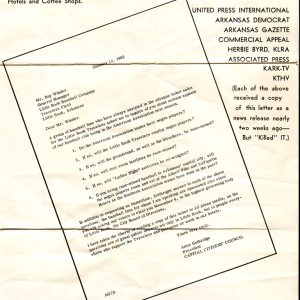

Dick Allen  Capital Citizens' Council Anti-integration Flyer

Capital Citizens' Council Anti-integration Flyer  Capital Citizens' Council Graphic

Capital Citizens' Council Graphic  Central High School

Central High School  Desegregation of Central High School Protest Rally

Desegregation of Central High School Protest Rally  Desegregation Protest at Capitol

Desegregation Protest at Capitol  Desegregation Protesters

Desegregation Protesters  Elizabeth Eckford Denied Entrance to Central High

Elizabeth Eckford Denied Entrance to Central High  Effigy Hanging

Effigy Hanging  Elaine Massacre Prisoners

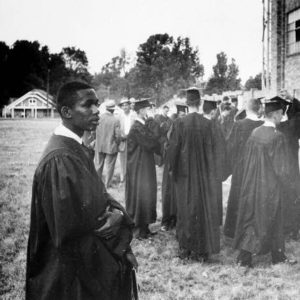

Elaine Massacre Prisoners  Ernest Green

Ernest Green  Hoxie Glee Club

Hoxie Glee Club  Silas Hunt

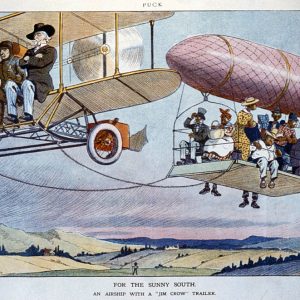

Silas Hunt  Jim Crow Laws Cartoon

Jim Crow Laws Cartoon  Edith Irby Jones

Edith Irby Jones  Little Rock Nine Monument

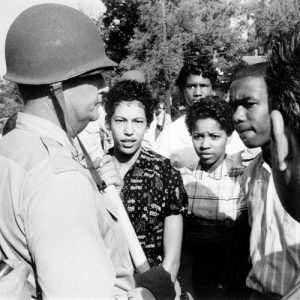

Little Rock Nine Monument  National Guardsman Confronts Students at Central High

National Guardsman Confronts Students at Central High  Segregated Waiting Room

Segregated Waiting Room  Segregated Waiting Room Door

Segregated Waiting Room Door  Segregated Water Fountain

Segregated Water Fountain  STOP Rally

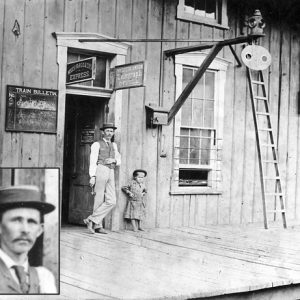

STOP Rally  Streetcar Segregation Act of 1903

Streetcar Segregation Act of 1903  Three of the North Little Rock Six

Three of the North Little Rock Six  Thurgood Marshall and Central High Students

Thurgood Marshall and Central High Students  Van Buren Desegregation

Van Buren Desegregation  White Protesters

White Protesters

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.