calsfoundation@cals.org

Roman Catholics

aka: Catholics

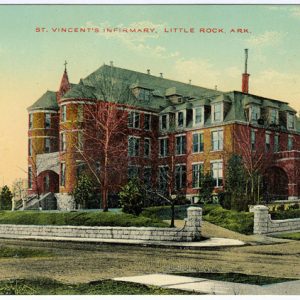

Roman Catholicism is the oldest form of Christianity in the state, yet it has remained the faith of a minority of the population. Catholicism first arrived in Arkansas via Spanish explorers and a French Jesuit missionary, and there were a few Catholics living at Arkansas Post during the French and Spanish colonial era of the eighteenth century. Once Arkansas became attached to the American Union by the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the area underwent a demographic and religious metamorphosis. A wave of Anglo-American Protestants migrated to the region so that, by 1850, Catholics made up approximately one percent of the total population of the state. The great European migration to the United States between 1840 and 1920, which contained millions of Catholics, missed the South generally and Arkansas in particular. The Catholic Diocese of Little Rock was established in 1843, and both then and now, its ecclesiastical jurisdiction encompasses the present boundaries of Arkansas. Catholics founded Arkansas’s oldest educational institution, Mount St. Mary Academy (founded as St. Mary’s Academy in 1851), and the oldest hospital in the state, St. Vincent Infirmary (1888), both institutions located in Little Rock (Pulaski County). Yet not until 1960 did Catholics make up more than two percent of the total population. The Catholic religious leadership has been remarkably stable, with several long-serving bishops having led the Church in Arkansas since 1843. Since 1980, however, Roman Catholics have increased in their percentage of the state population. This is due to an increase in conversions, an influx of northern retirees (many Catholic), plus a major migration of Hispanics into the state. By the first decade of the twenty-first century, the number of Catholics in Arkansas was just below four percent, but the number had increased by 2020, making the Catholic Church the third-largest religious group in the state, with a concentration in northwestern Arkansas.

Hernando de Soto and his fellow Spaniards became the first Catholics to enter what is now Arkansas on June 18, 1541. On the western side of the Mississippi River, de Soto erected a cross at the town of Casqui near modern-day Parkin (Cross County) and knelt before it singing a Te Deum, a Catholic hymn of praise; this was the first Christian worship service ever held in Arkansas. The conquistador stayed in the future state less than a year, and Spain, preoccupied by its holdings farther south, never attempted to occupy Arkansas. Over 130 years later, French Jesuit missionary Father Jacques Marquette arrived in what is now Arkansas and visited some Quapaw in July 1673. On November 1, 1700, French Jesuit Fr. Jacques Gravier celebrated the first Catholic mass in Arkansas along the Mississippi River at a Quapaw village. Jesuit Fr. Paul du Poisson labored among the eastern Arkansas tribes from 1726 to 1729 before being killed in Mississippi by the Natchez on November 28, 1729. (This was exactly 114 years to the day before the establishment of a Catholic diocese for Arkansas.) Few priests came to Arkansas throughout the eighteenth and well into the nineteenth century. By the time Pope Gregory XVI erected the Diocese of Little Rock, the longest time a Catholic priest had been in Arkansas was eight years; this was yet another French Jesuit, Fr. Louis Carette, who was in the state from 1750 to 1758.

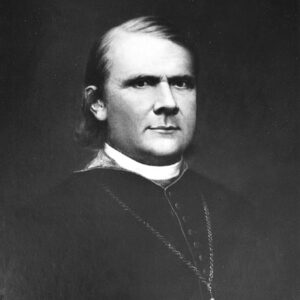

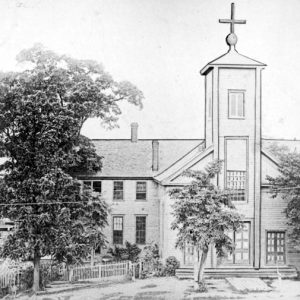

For the duration of the nineteenth century, Arkansas had two Irish-born prelates, Andrew Byrne (1802–1862) and Edward Mary Fitzgerald (1833–1907). Byrne arrived in 1844, and throughout his eighteen years as bishop, he never had more than ten priests. After dedicating Arkansas’s first St. Andrew’s Cathedral in Little Rock in 1846, Byrne founded Arkansas’s first Catholic college, St. Andrew’s near Fort Smith (Sebastian County), three years later. This Irish-born prelate enticed the Sisters of Mercy to come to Arkansas from his native isle. These sisters soon started St. Mary’s Academy in Little Rock in 1851. By 1860, the sisters had founded additional academies: St. Anne’s Academy in Fort Smith and Saint Catherine’s in Helena (Phillips County). Byrne had more difficulty getting any more Irish immigrants to come to Arkansas, even after making two trips back to Ireland to induce such migration. By 1860, the number of Catholics stayed around one percent of the population. Aware of the intense minority status of Arkansas’s Catholics, Byrne shied away from political disputes during a brief anti-Catholic uproar known in history as the Know-Nothing movement. This movement was both anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic and spawned a national political party called the American Party (or Know-Nothing Party), which operated in Arkansas from 1855 to 1856. Byrne neither owned slaves nor expressed any opinion on African slavery. The onset of the Civil War forced Arkansas’s first Catholic college to close in 1861.

The Civil War disrupted communications between Rome and Arkansas, and so the state did not see another Catholic bishop until 1867. Edward M. Fitzgerald was only thirty-three when he accepted his appointment. Arriving in Little Rock on St. Patrick’s Day, Bishop Fitzgerald found only five priests to serve a diocese which was, like most of the South after the war, bankrupt. Fitzgerald, however, came to be the most historically significant person in Arkansas Catholic history. He was the only English-speaking bishop, and one of only two prelates in the world, to vote against the declaration of papal infallibility at the First Vatican Council in Rome in 1870. This action, plus his later opposition to the establishment of parish schools and his sympathy with the early labor movement, marks Fitzgerald as one of the most interesting, yet overlooked, prelates in American Catholic history. Like his predecessor, Fitzgerald attempted to lure Catholics to the state—not just Irish but also those from Germany, Switzerland, Italy, and Poland. These immigrants settled mainly, but not exclusively, along the Arkansas River from Little Rock to Fort Smith and in northwestern corner of the state. Fitzgerald also made a largely unsuccessful effort to evangelize African Americans to Catholicism. Despite his efforts, by 1900, Catholics still amounted to about one percent of the state’s population.

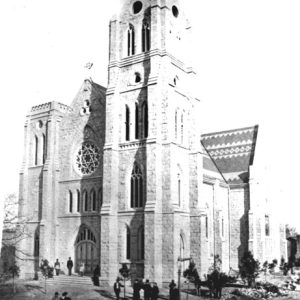

Fitzgerald erected the present St. Andrew’s Cathedral in Little Rock in 1881 and, seven years later, St. Vincent Infirmary, which he also helped to staff by bringing to the state the Sisters of Charity from Nazareth, Kentucky. By 1905, Arkansas had three more Catholic hospitals operating: St. Joseph’s in Hot Springs (Garland County), later renamed St. Vincent Hot Springs; St. Bernard’s in Jonesboro (Craighead County); and St. Edward’s in Fort Smith, renamed Mercy Fort Smith in 2012. A century later, there were twelve Catholic medical facilities operating in Arkansas. In 1878, Benedictines from Indiana founded New Subiaco Abbey (now called simply Subiaco Abbey) in Logan County, just south of the Arkansas River. This men’s monastery has remained a center for Catholic worship and education in western Arkansas for more than a century. In addition to this men’s religious order, new women’s Benedictine religious orders were started in western Arkansas in Logan County in 1879; by 1925, they had moved to Fort Smith and established their motherhouse, St. Scholastica’s Monastery. Across the state, a group of sisters from Missouri came to Pocahontas (Randolph County) in 1887, and they eventually aligned themselves with the Olivetan Benedictines based in Switzerland. In 1898, they moved from Pocahontas to Jonesboro, opening Holy Angels Convent.

Arkansas, at this time, had some notable converts to the faith. In 1890, Arkansas elected its first Catholic member of the U.S. House of Representatives, Congressman William Leake Terry. A convert from a distinguished Arkansas family, Terry represented Little Rock and the Arkansas River Valley to the Oklahoma line as a Democrat for a decade. On November 15, 1896, at the fervent behest of his Irish wife, Judge Isaac Parker, the state’s famous federal judge, converted to Catholicism just two days before his death.

Bishop Edward Fitzgerald’s career ended when he suffered a stroke in 1900; by that time, there were forty-three priests operating in Arkansas. Fitzgerald remained an invalid in St. Joseph Catholic hospital in Hot Springs until his death on February 21, 1907. Between 1900 and 1906, the diocese’s operations were conducted by German-born Benedictine Fr. Fintan Kraemer.

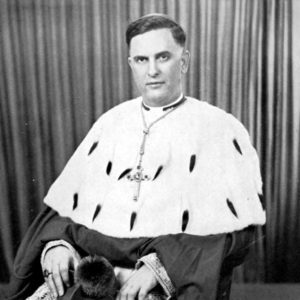

During the twentieth century, the Arkansas Church had only three prelates. Born near Hendersonville, Tennessee, Bishop John B. Morris (1866–1946) came to Arkansas in the summer of 1906 as coadjutor bishop, giving him the right of succession upon Fitzgerald’s death. During his tenure, a Catholic weekly began in 1911, first called The Southern Guardian; its name was shortened in 1915 to The Guardian, a title it kept until 1986, when it became known as the Arkansas Catholic. Morris opened Arkansas’s second Catholic institution of higher education, Little Rock College, in 1908. The Great Depression closed it in 1930, and its facilities became the Little Rock Catholic High School for Boys. Morris also opened the Seminary of St. John the Baptist in 1911, which lasted for fifty-six years.

Arkansas did experience an upsurge of anti-Catholicism in the first two decades that Morris served as bishop. Tom Watson after 1910, and the Klan during the 1920s, caused anti-Catholicism to swell in the South, and it also affected Arkansas. In 1915, the state legislature passed the Posey Act, or Convent Inspection Act. This act authorized county and local law enforcement authorities to make annual inspections of Catholic convents, rectories, and monasteries. This act was quietly repealed in 1937. Some bigotry certainly remained, but it generally subsided after World War II.

The forty-year episcopacy of Morris witnessed tremendous growth in the Catholic Church in Arkansas. There were only sixty priests when he came in 1906, yet by the time of his death, there were 154 priests in the diocese. In 1900, there were only 150 religious sisters in the diocese, but by 1946, there were 582 sisters working in schools, hospitals, and orphanages. Twenty Catholic high schools and sixty parish schools were educating some 7,710 students by the end of his episcopacy. In 1905, there were only two small Black Catholic churches; four decades later, there were nine black Catholic parishes, with seven affiliated schools. One important Black layman was Daniel Rudd, who represented Black Catholics in Arkansas at a number of conferences and conventions. By 1946, the Catholic population equaled about 1.7 percent of the total population.

On April 25, 1940, Arkansas had its first native-born Catholic prelate with the consecration of Albert L. Fletcher (1896–1979) as auxiliary bishop at St. Andrew’s Cathedral in Little Rock. Born in the state capital, raised primarily in western and northern Arkansas, and educated at St. John’s Seminary, Fletcher had been a priest since 1920. As the auxiliary prelate, Fletcher did not automatically assume the office upon the death of Morris; nevertheless, in 1947, he became Arkansas’s fourth Catholic bishop. As bishop, Fletcher dedicated the Catholic shrine Our Lady of the Ozarks near Winslow (Washington County) in 1950 and led the Family Rosary Crusade held in Little Rock, Fort Smith, and Jonesboro in 1952. In 1954, he led a special Holy Hour Adoration of Christ in the Eucharist held at Robinson Auditorium in Little Rock.

In 1957, the nation and the world focused upon the controversy around racial integration at Little Rock Central High. Fletcher supported peaceful integration and wrote a small catechism in 1960 focusing attention against racism and segregation. Integration proceeded in the diocese, much to the detriment to Black Catholic schools and parishes, the numbers of which went from eleven Black parishes, seven grade schools, and two Black Catholic high schools in Little Rock and Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) in 1960 to just three churches and three grade schools twelve years later. Three Black Catholic parishes and one school survived to the end of the twentieth century. The last predominately Black Catholic school in Arkansas, St. Peter School in Pine Bluff (which taught elementary grades), closed in May 2012. Overall, the Black Catholic population in Arkansas has remained small, even though many African Americans sent their children to Catholic schools. The closing of the schools did not significantly impact the Black Catholic population.

Bishop Fletcher attended all four fall sessions of the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965). While he never addressed the council, he wrote thirteen interventions, nine of which were accepted by the whole council and put into the final documents. Personal and doctrinal strife within St. John’s Seminary caused Bishop Fletcher to close that institution in 1967. While much of the Catholic world was soon in turmoil over the interpretation and implementation of Vatican II, Fletcher faced doctrinal and questions of authority from younger professors who were far more liberal than most Arkansas Catholics and the bishop at that time, including Father James F. Drane, who had published editorials in the Arkansas Gazette decrying Catholic teachings on birth control and papal infallibility. The former seminary grounds began housing the offices of the diocese, which were moved from downtown Little Rock.

Born in Texarkana (Miller County), Lawrence P. Graves (1916–1994) became auxiliary bishop on April 25, 1969, yet he was not chosen as Fletcher’s successor in 1972. Instead, Pope Paul VI selected Savannah, Georgia, native Andrew J. McDonald (1923–) as Arkansas’s fifth bishop. Graves became Bishop of Alexandria-Shreveport in 1973, serving there for nine years until ill health forced his retirement; he died in Louisiana in 1994. Bishop Fletcher spent only seven years in retirement until his death in Little Rock.

Bishop McDonald and his successors had to confront a decline in religious vocations after Vatican II, combined with an overall increase in the Catholic population. The number of Catholic priests in Arkansas shrank from 190 in 1965 to 120 by 2005. The number of sisters in Arkansas fell from 693 to 234 over the same period of time. In the midst of this decline, the number of Catholics in the state grew dramatically, especially after 1980. After the smallest increase of Catholic population in the twentieth century during the 1970s, the number of Catholics jumped from 56,911 to 107,524 by 2005, or from 2.4 percent of the population in 1980 to 3.9 percent a quarter century later. In the twenty-first century, newer churches and chapels have been constructed, often in areas of the state that have never had a Catholic presence, such as northwestern Arkansas. Since 1972, the diocese has had an office outreach to Spanish-speaking Catholics. An annual Hispanic Catholic event called Encuentro is held in North Little Rock (Pulaski County), and thousands attend each year. Many Spanish-speaking Catholics would attend mass but often fail to register locally in the parishes, so estimates of their numbers at certain points in history could often be inaccurate.

During the last three decades of the twentieth century, lay-inspired faith renewal movements from outside the state came to Arkansas, such as the Spanish retreat-centered Cursillo and the charismatic movement. Arkansas Catholics not only participated in these renewal movements but began one which has impacted the whole church. In 1974, Fred and Tammy Woell, a Catholic couple in Little Rock, launched a Scripture study program based on the theology of the Abbot Fr. Jerome Kodell, which spread, with the help of Arkansas’s prelates, across the United States and the world. The Little Rock Scripture Study program and materials have been widely used and translated into many languages.

In 1982, Mother Teresa of Calcutta came to Little Rock to open her Abba House for unwed mothers, run by members of her order, Missionaries of Charity. Mother Teresa and Bishop McDonald appeared together at a special rally at Ray Winder Baseball Field in Little Rock on June 2, 1982. Singer, songwriter, and world-renowned Catholic liturgist John Michael Talbot came to the state in 1982 from Indiana and eventually formed his own Little Portion Franciscan community near Eureka Springs (Carroll County); it was officially sanctioned by the Diocese of Little Rock in 1990.

Bishop McDonald submitted his resignation upon reaching the now-mandatory retirement age of seventy-five in 1998. As his successor, Pope John Paul II appointed Fr. James Peter Sartain (1952–), a native of Memphis, Tennessee; he was consecrated as Arkansas’s sixth bishop at the Little Rock Convention Center on March 6, 2000. Bishop McDonald retired to Chicago to serve as a chaplain for the Little Sisters of the Poor. On May 16, 2006, Bishop Sartain was appointed to head up the Diocese of Joliet in Illinois, and the Diocese of Little Rock was sede vacante (Latin for “the seat being vacant”), or without a bishop, until April 10, 2008, when Anthony B. Taylor of Oklahoma City was appointed.

Among the issues Bishop Taylor confronted was that of immigration, as he sought to include greater Latino representation in the diocese as well as soften attitudes toward immigrants in Arkansas at large. Too, in the wake of ongoing revelations about cases of child rape in the Roman Catholic Church across the United States and the world, and related conspiracies of silence, on September 10, 2018, Bishop Taylor released a list of twelve priests against whom “credible allegations” of child sexual abuse had been leveled during the several previous decades; he also acknowledged that victims of abuse had been paid. The following month, the diocese acknowledged that twenty-six additional cases of child sexual abuse had been reported since the release of the original list.

For additional information:

Agee, Gary. A Cry for Justice: Daniel Rudd and His Life in Black Catholicism, Journalism, and Activism, 1854–1933. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2011.

Archives of the Diocese of Little Rock. St. John’s Catholic Center, Little Rock, Arkansas

Archives of the Archdiocese of New Orleans. Old Ursuline Convent, New Orleans, Louisiana.

Arkansas Catholic: The Official Newspaper of the Diocese of Little Rock. http://www.arkansas-catholic.org/ (accessed July 6, 2023).

Assenmacher, Hugh, OSB. A Place Called Subiaco: A History of the Benedictine Monks in Arkansas. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Company, 1977.

Barnes, Kenneth C. Anti-Catholicism in Arkansas: How Politicians, the Press, the Klan, and Religious Leaders Imagined an Enemy. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2016.

Brandon, Jamie C., and Jerry E. Hilliard. “Zachary Taylor and the Sisters of Mercy: An Archaeology of Memory, Landscape, Gender, and Faith on Arkansas’s Western Frontier.” In Historical Archaeology of Arkansas: A Hidden Diversity, edited by Carl G. Drexler. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2016.

Catholicism on the Mississippi: The Helena Story. Little Rock: Arkansas Graphics, 2012.

Diocese of Little Rock. http://www.dolr.org/ (accessed July 6, 2023).

Historical Commission of the Diocese of Little Rock. The History of Catholicity in Arkansas, from the Earliest Missionaries Down to the Present Time. Little Rock: The Guardian, 1925. Online at https://arstudies.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15728coll3/id/559720/rec/1 (accessed July 6, 2023).

Hockle, M. Henrietta, OSB. “Catholic Schools in Arkansas: A Historical Perspective, 1838–1977.” EdS thesis, Arkansas State University, 1977.

———. On High Ground: A History of the Olivetan Benedictine Sisters, Jonesboro, Arkansas, 1887–2003. Jonesboro, AR: Pinpoint Printing, Inc., 2004.

———. Promises Kept: Reflections of a Century: The Olivetan Benedictine Sisters, Jonesboro, Arkansas. Little Rock: Porbeck Printing Co., 1986.

Jones, Linda Carol. The Shattered Cross: French Catholic Missionaries on the Mississippi River, 1698–1725. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2020.

Jones, Scott. “Monastic Missionaries in the New Wilderness: A History of Monasticism in Arkansas, 1878–1998.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 1998.

Justiss, William B. “The Black Robes of Arkansas: Jesuit Missionaries and Arkansas Post, 1673–1758.” Pulaski County Historical Review 22 (June 1974): 31–41.

Landers, Misty. “Just Discrimination: Arkansas Parochial Schools and the Defense of Segregation.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2017. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2407/ (accessed July 6, 2023).

———. “Just Discrimination: The Catholic Church in Arkansas and School Integration after Brown v. Board of Education.” Ozark Historical Review 36 (Spring 2007): 31–43.

Moran, Michael. Proudly We Speak Your Name: Forty-four Years at Catholic High School, Little Rock. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2009.

Newman, Mark. “The Catholic Church in Arkansas and Desegregation, 1946–1988.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 66 (Autumn 2007): 293–319.

———. Desegregating Dixie: The Catholic Church in the South and Desegregation, 1945–1992. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2018.

Newspaper Archive of the Arkansas Catholic. http://arc.stparchive.com/ (accessed July 6, 2023).

Peck, Hannah F. “St. Vincent’s Infirmary, 1888–1987: A History of a Roman Catholic Hospital in Little Rock, Arkansas.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 1987.

Ramos, Jane. Arkansas Frontiers of Mercy: A History of the Sisters of Mercy in the Diocese of Little Rock. Fort Smith, AR: St. Edward’s Press, 1989.

Sharum, Louise, OSB. Write the Vision Down: A History of St. Scholastica’s Convent, Fort Smith, Arkansas, 1879–1979. Fort Smith, AR: American Printing and Lithography Co., 1979.

Sitzer, Mary Jean. “Preserving a Catholic Community: The History of St. Anthony’s Catholic Church in Weiner, Arkansas.” PhD diss., Arkansas State University, 2021.

University of Notre Dame Archives. Hesburgh Library. University of Notre Dame, South Bend, Indiana.

Voth, Mary Ann, OSB. Green Olive Branch. Chicago: Franciscan Herald Press, 1976.

Weibel, John E. The Catholic Missions of North-east Arkansas, 1867–1893. Jonesboro: Arkansas State University Press, 1967.

———. Forty Years Missionary in Arkansas. Jonesboro, AR: Holy Angels Convent, 1968.

Woods, James M. A History of the Catholic Church in the American South, 1513–1900. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2011.

———. Mission and Memory: A History of the Catholic Church in Arkansas. Little Rock: August House Publishing Co., 1993.

———. “To the Suburb of Hell: Catholic Missionaries in Arkansas, 1803–1843.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 48 (Autumn 1989): 218–242.

James M. Woods

Georgia Southern University

Religion

Religion Atkins Church

Atkins Church  Pietro Bandini

Pietro Bandini  Andrew Byrne

Andrew Byrne  Carmelite Monastery of St. Teresa of Jesus

Carmelite Monastery of St. Teresa of Jesus  Carmelite Monastery of St. Teresa of Jesus

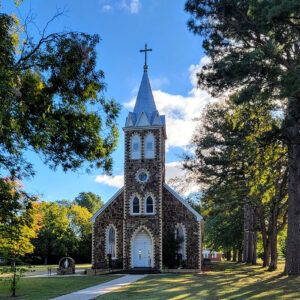

Carmelite Monastery of St. Teresa of Jesus  Cathedral of St. Andrew

Cathedral of St. Andrew  Cathedral of St. Andrew

Cathedral of St. Andrew  Conway Church

Conway Church  St. Elizabeth's Catholic Church

St. Elizabeth's Catholic Church  Edward Fitzgerald

Edward Fitzgerald  Edward Fitzgerald

Edward Fitzgerald  Albert Fletcher

Albert Fletcher  Albert Fletcher

Albert Fletcher  Fort Smith Catholic Church

Fort Smith Catholic Church  Hartman Catholic Church

Hartman Catholic Church  Holy Angels Convent

Holy Angels Convent  Holy Angels Convent

Holy Angels Convent  Immaculate Conception Church

Immaculate Conception Church  Fintan Kraemer

Fintan Kraemer  Marche Catholic Church

Marche Catholic Church  May Crowning

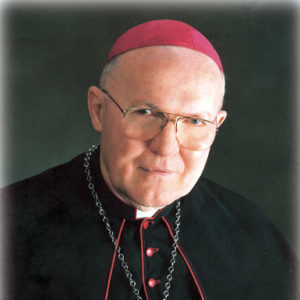

May Crowning  Andrew McDonald

Andrew McDonald  Andrew McDonald

Andrew McDonald  Monastery of the Order of Our Lady of Charity

Monastery of the Order of Our Lady of Charity  John Baptist Morris

John Baptist Morris  John Baptist Morris

John Baptist Morris  John Baptist Morris

John Baptist Morris  Mother Teresa Press Conference

Mother Teresa Press Conference  Paris Church

Paris Church  Sacred Heart Academy

Sacred Heart Academy  Sacred Hearts Rectory

Sacred Hearts Rectory  Saint Mary’s Catholic Church

Saint Mary’s Catholic Church  Peter Sartain

Peter Sartain  St. Edward Catholic Church

St. Edward Catholic Church  St. Elizabeth's Catholic Church

St. Elizabeth's Catholic Church  St. Ignatius Catholic Church

St. Ignatius Catholic Church  St. Joseph's Home

St. Joseph's Home  St. Joseph's Home Entrance

St. Joseph's Home Entrance  St. Mary's Convent

St. Mary's Convent  St. Meinrad Catholic Church

St. Meinrad Catholic Church  St. Scholastica Monastery

St. Scholastica Monastery  St. Scholastica Monastery

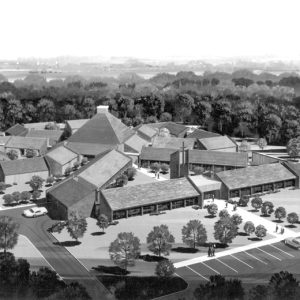

St. Scholastica Monastery  St. Vincent Infirmary Dedication

St. Vincent Infirmary Dedication  St. Vincent Infirmary

St. Vincent Infirmary  Sts. Peter & Paul Catholic Church

Sts. Peter & Paul Catholic Church  St. Benedict's Church at Subiaco

St. Benedict's Church at Subiaco  Tontitown Catholic Church

Tontitown Catholic Church  Eugene John Weibel

Eugene John Weibel

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.