calsfoundation@cals.org

Public Works Administration

The U.S. Congress passed the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) on June 16, 1933, as part of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal to combat the effects of the Great Depression and the ensuing failures of businesses across the country. As part of the act, the Federal Emergency Administration of Public Works—called the Public Works Administration (PWA) after 1935—was established on June 16, 1933, to provide grants and loans to finance public works projects that would help “promote and stabilize employment and purchasing power.” Across the country, the PWA funded some 34,000 projects between July 1933 and March 1939, expending $6 billion over the lifetime of the agency.

President Herbert Hoover had sought to establish a public works division within the Department of the Interior, a bid that was stalled by his defeat by Roosevelt in the 1932 presidential election. But while Hoover’s objective was a simple reorganization of federal public works agencies, Roosevelt’s aim under NIRA was to put unemployed Americans to work on public projects funded through a system of federal grants and loans. State and local governments could get grants for up to thirty percent of labor costs, plus the cost of materials, for projects suggested by the PWA, private contractors, or other federal agencies. PWA loans were available to cover expenses above the grants awarded for projects.

Federal Public Works Administrator Harold Ickes established a system under which state PWA programs would be overseen by a regional adviser assisted by an engineer-administrator and a three-person advisory team that would make recommendations on which project proposals should be financed. Projects that would provide tangible resources—including waterworks, sewer systems, highway projects, hospitals, and municipal buildings—were the most desirable, and accepted projects were expected to commence construction immediately and to be completed in a timely manner. They needed to cost a minimum of $25,000, and new construction projects in high-unemployment areas were preferred. Congress initially set aside $3.3 billion for NIRA projects, including $400 million for state highway projects. Arkansas received a special waiver from matching requirements for its $6,748,335 highway allotment because of the state’s financial instability.

PWA projects were intended to “prime the pumps” of local economies, and federal requirements called for applicants to provide details about both employment and purchasing power in the areas where projects were located, as state and local governments—not the federal government—would maintain the new facilities.

The PWA was initially authorized for two years. It was extended to June 1937 by the Emergency Relief Appropriations Act of 1935, and to July 1939 by the Public Works Administration Extension Act of 1937. The 1938 Public Works Administration Appropriations Act approved $1.365 billion for projects that were to be finished by June 1940, and the agency was to be liquidated in June 1941, which fit in with Roosevelt’s goals as he prepared for a wartime industrial effort.

The PWA had a major impact on Arkansas’s infrastructure. At least 235 projects were completed through the PWA in the state, including 124 city water and sewer projects that were financed by $9,280,449 in grants and loans. At least twelve courthouses, nine city halls, and eleven county and city jails were constructed using $2,118,987 in PWA funds. College buildings, public schools, swimming pools, levees, and hospitals were constructed with the assistance of the PWA. The single most expensive Arkansas project was the Saline County Hospital, which used $1,769,000 in PWA grants and loans.

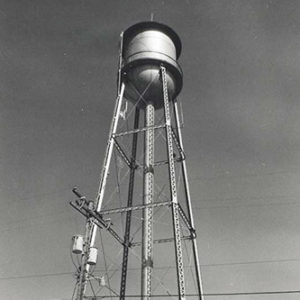

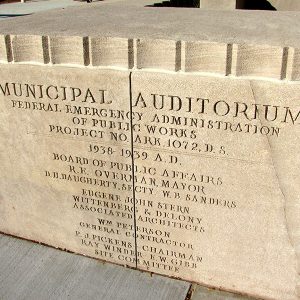

At least twenty-five PWA-funded properties in Arkansas are listed on the National Register of Historic Places, including the Craighead County Courthouse (listed September 11, 1998), the Cross and Nelson Hall Historic District (listed January 20, 2010), the Green Forest Water Tower (listed May 22, 2007), the Hampton Waterworks (listed October 5, 2006), the Howard County Courthouse (listed June 14, 1990), the Hughes Water Tower (listed October 5, 2006), the Joseph Taylor Robinson Memorial Auditorium (listed February 21, 2007), the Lee County Courthouse (listed September 7, 1995), the Mountain View Waterworks (listed October 5, 2006), the Physical Education Building at Arkansas Tech University (listed September 10, 1992), the Scott County Courthouse (listed November 13, 1989), and the Van Buren County Courthouse (listed May 13, 1991).

For additional information:

Federal Works Agency Public Works Administration. “List of all Allotted Non-Federal Projects, All Programs, By State and Docket, as of May 30, 1942.” In the files of the Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Hope, Holly. “An Ambition to be Preferred: New Deal Recovery Efforts and Architecture in Arkansas, 1933–1943.” Little Rock, Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, 2006. Online at http://www.arkansaspreservation.com/News-and-Events/publications (accessed October 2, 2020).

Isakoff, Jack. The Public Works Administration. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1938.

Mark K. Christ

Little Rock, Arkansas

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Historic Preservation

Historic Preservation Politics and Government

Politics and Government Craighead County Courthouse

Craighead County Courthouse  Green Forest Water Tower

Green Forest Water Tower  Hampton Waterworks

Hampton Waterworks  Howard County Courthouse

Howard County Courthouse  Hughes Water Tower

Hughes Water Tower  Mountain View Waterworks

Mountain View Waterworks  Robinson Center Cornerstone

Robinson Center Cornerstone  Robinson Center Music Hall

Robinson Center Music Hall  Scott County Courthouse

Scott County Courthouse  George Trapp

George Trapp  Van Buren County Courthouse

Van Buren County Courthouse

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.