calsfoundation@cals.org

Penters Bluff (Izard County)

aka: Penter’s Bluff (Izard County)

The historic community of Penters Bluff is located on the White River about six and a half miles southeast of Guion (Izard County) and approximately five miles west of Cushman (Independence County). Penters Bluff and the neighboring railroad towns of Switch and Crocker have disappeared without much of a trace. Named for John Penter and family, whose name was often pronounced Painter, the bluff (or really a collection of bluffs) is sometimes called by that name and also by Panthers, Panters, and even Pinters Bluff; the apostrophe is usually left out between the “r” and the “s” in Penter’s Bluff but not always.

The main reason Penters Bluff is still on the map is its breath-taking beauty, which attracts tourists and photographers. The bluff is fairly easy to reach by way of the Younger Access Road across the river in Stone County, by a boat on the White River, or by walking on the railroad tracks that run below the bluff. There is also a country road that leads to the bluffs.

The bluffs are made of limestone and silica. Evidence of an old lime quarry has been found on the site. By 1849, a large range of manganese ore deposits had been discovered in northwestern Independence County with a spillover into Izard, Stone, and Sharp counties. This discovery came to be labeled the Batesville District, with Cushman at its center. The first recorded mention of the manganese deposits was from Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s writings as he made his exploration of the White River in 1819. In 1848, a state geologist mentioned the presence of manganese at Penters Bluff. However, significant mining operations in the Batesville District did not begin until 1885, when the Keystone Mining Company (owned by Andrew Carnegie) and the St. Louis Mining Company began operations in the Southard Hill region near Cushman.

Steamboat travel on the upper White River, north-northwest of Jacksonport (Jackson County), began in 1831. Colonel Matt Martin of Batesville (Independence County) owned the Penters Bluff steamboat landing, a main stop for steamboats plying the White River, and it was a typical steamboat stop for the era. Wall’s Ferry carried passengers across the White River from what is now Pleasant Grove (Stone County), St. James (Stone County), and Marcella (Stone County) to Penters Bluff. Lock and Dam No. 3 was built near the ferry site around 1903.

Grandison Moses Wall, who built the ferry between 1851 and 1860, also built a warehouse where he stored supplies and farm equipment brought in by boat up the river. This provided necessities and equipment to the settlers in the area. Grandison Wall was appointed a member of the Homeland Guard when the Civil War began and enlisted as a private in the Confederate army at the Hess Ferry about four miles downstream.

Because of their strategic location, Penters Bluff and Wall’s Ferry played an important role in the Civil War, in particular the skirmish of Waugh’s Farm near what is today Bethesda (Independence County) and the skirmish at Buck Horn (which is now St. James). In February 1864, Confederate captain George Rutherford crossed the White River below Penters Bluff heading for Waugh’s Farm, where a Union foraging party was camped. The Union forces were taken by surprise in the early hours of day, and a rout ensued. Captain Rutherford and his Confederates were victorious. The notorious bushwhacker Bill Williams, who was a Union sympathizer, and his band of irregulars holed up near Wall’s Ferry and became a scourge to the countryside. Williams and his gang were stopped at Buck Horn on May 25, 1864, with a Confederate victory by Brigadier General Joseph Shelby.

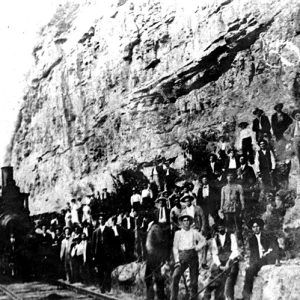

After the Civil War, railroads began to replace steamboats as freight haulers and providers of passenger travel. The St. Louis, Iron Mountain and Southern Railway was completed from Batesville to Cotter (Baxter County) following the north bank of the White River by fall 1903, and daily passenger service from Newport (Jackson County) to Batesville to Cotter was available, with the train going through Penters Bluff. The tracks were extended to Carthage, Missouri, by 1906. With the building of the railroad along the northern banks of the White River came railroad workers who resided for a time in tents at Penters Bluff.

With the railroad came the post office, which was established on November 8, 1906, with James Hines appointed its first postmaster. The Penters Bluff Post Office closed in 1919. A short-lived post office had existed for a few months in 1903; it was called Penter, with Henry C. Neely serving as postmaster.

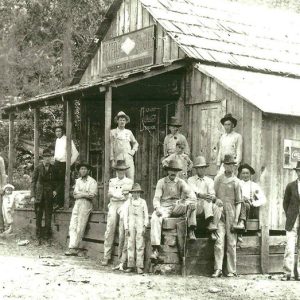

According to local historian Martin M. Martin, one of the first stores in Penters Bluff was Crocker’s General Store and Trading Post at the Crocker Spur on the upper end of Penters Bluff; it was run by a series of proprietors including Bill Gideon, Iron Pence, and Henry Owens, who had the last post office there in 1919. Walter Haydn had a store moved from nearby Guion to Penters Bluff in the early 1900s. The most remembered store was run by James Monroe (Jim) Lovelady and John Hill Sheffield in the early 1900s. Jim Lovelady and Hill Sheffield also had separate stores in Guion.

Considered by many to have been one of the best cotton gins in the area, Glenn’s Gin built by John W. Glenn was located near Wall’s Ferry and Penters Bluff. A tornado destroyed the gin in 1916, but it was rebuilt by a new owner, Jasper Johnson, a few months later and continued to operate until the market for cotton goods declined after World War II.

In the twenty-first century, all that remains of the Penters Bluff community are the beautiful bluffs and Lock and Dam No. 3.

For additional information:

Crain, Tracy. “Penter’s Bluff Is an Izard County Tourist Attraction That Is Home to Some Interesting Stories.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Three Rivers Edition, January 7, 2001, p. 9S.

Huddleston, Duane, Sammie Cantrell Rose, and Pat Taylor Wood. Steamboats and Ferries on the White River: A Heritage Revisited. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1998.

McAdams, Virginia. “The Battle of Waugh’s Farm.” Independence County Chronicle 2, no. 4 (1961): 3–6.

Mobley, Freeman K. Making Sense of the Civil War in Batesville–Jacksonport and Northeast Arkansas. Batesville, AR: Frank K. Mobley, 2005.

Smith, Jim, and Becky Wood. The Cushman Manganese Mines and the Batesville Manganese District Arkansas. N.p.: 1995.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe. Journal of a Tour into the Interior of Missouri and Arkansaw. London: Sir Richard Phillips and Co., 1821.

———. Rude Pursuits and Rugged Peaks: Schoolcraft’s Ozark Journal 1818–1819. Edited by Milton D. Rafferty. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1996.

Kenneth Rorie

Van Buren, Arkansas

Iron Mountain Railway Crew

Iron Mountain Railway Crew  Izard County Map

Izard County Map  Lovelady General Store

Lovelady General Store  Penters Bluff

Penters Bluff  Railway at Penters Bluff

Railway at Penters Bluff

I discovered Younger Access while driving home from Mountain View on a Sunday afternoon. What a surprise! The view is spectacular, and that county has good roads! Love exploring Arkansas and learning about our natural resources and history.