calsfoundation@cals.org

Paroling (Civil War)

Paroling was a typical method used in dealing with military prisoners during the Civil War. Troops captured in battle were often offered the chance to sign a parole and return to their own lines with the promise that they would avoid active service until they were officially exchanged. Only after they were officially exchanged could the troops legally reenter active service.

A formal system for handling prisoners of war did not exist at the outbreak of the war. Several issues, including the legality of the Confederacy itself and questions on how to treat captured privateers, delayed the implementation of a nationwide system for months. Many troops captured in the earliest battles were held in prisons as the exchange system was created. Many captured troops who were wounded were paroled or simply released and returned to their respective armies to relieve some of the stress for the captors of providing medical care.

Arkansans who were captured in early battles such as Island Number Ten and Fort Donelson were transported to northern prison camps but were eventually exchanged. Troops who were paroled back to their respective army but had not yet been officially exchanged were technically prevented from engaging in hostile action against the enemy. However, the troops could be used to guard prisoners of war or railroads and perform other military tasks that kept them from direct contact with the enemy.

Paroling became firmly established with the Dix-Hill Cartel agreement signed on July 22, 1862. The cartel called for all prisoners to be paroled within ten days of their capture and established two locations for the exchange of prisoners: Aiken’s Landing, Virginia, and Vicksburg, Mississippi. The practice worked well for several months until the Confederacy suspended the parole and exchange of officers in December. In 1863, the Confederate army began to refuse to parole captured African-American troops. By the summer, the entire system had collapsed. A more limited exchange system operated for several months in late 1863 and early 1864 until Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant stopped the process. He wanted equal treatment for African-American prisoners and sought to confirm the actual exchange of troops captured at Vicksburg and Port Hudson who had reentered active service. Other exchange systems operated before the end of the war, focusing mostly on sick prisoners, but the system never reached the numbers that were paroled and exchanged in the summer of 1862.

The largest capture of Arkansas troops during the war was associated with the Vicksburg campaign, with thousands taken prisoner at Fort Hindman, Helena (Phillips County), Port Hudson, and Vicksburg. The enlisted troops captured at Vicksburg and Port Hudson were quickly paroled, while the commissioned officers were transported up the Mississippi River to prison camps. The paroled troops from Port Hudson returned to Arkansas, where many re-formed their units or joined new regiments to continue their service in the Trans-Mississippi. Those captured at Vicksburg and Fort Hindman were eventually exchanged, and most served with the Army of Tennessee for the remainder of the war.

Paroled troops who returned to Arkansas often reorganized in Camden (Ouachita County) or other towns in the southern portion of the state. Federal commanders in the Vicksburg Campaign decided to parole these men to avoid the responsibility of feeding them or transporting them to the north; they also thought that large numbers of captured troops from Arkansas and the Trans-Mississippi would have a negative impact on morale in those states. Colonel Thomas Dockery was tasked by the Confederate War Department with reorganizing these men into effective units. Eventually, three complete regiments and one battalion were formed into a brigade under Dockery. The unit joined active service with the Confederate army, and many of these men saw action in the Camden Expedition. Dockery was promoted to brigadier general after the reorganization began.

When troops were officially exchanged after spending time on parole, they were informed that they would be allowed to return to active service. If a soldier was recaptured before being officially exchanged, he could be held by the enemy without any chance for parole.

The war ended with thousands of troops held in prison camps in both the North and South. While paroling did at least relieve some of the crowding that would have occurred in these camps during the war, it ultimately did not play a major role in preventing massive suffering by prisoners on both sides.

For additional information:

Hesseltine, William. Civil War Prisons: A Study in War Psychology. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing, 1964.

McAdams, Benton. Rebels at Rock Island: The Story of a Civil War Prison. DeKalb: Northern Illinois Press, 2000.

Williams, Charles. “A List of Confederate Citizen Prisoners Held at the United States Military Prison at Little Rock, Arkansas.” Pulaski County Historical Review 36 (Winter 1988): 82–92.

David Sesser

Henderson State University

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874 Military

Military Penal Systems

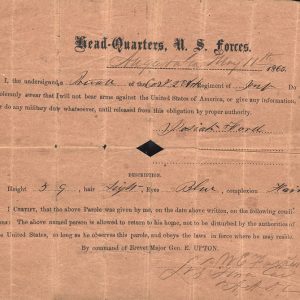

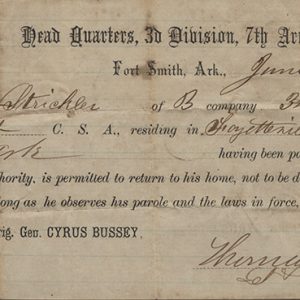

Penal Systems Paroling Document

Paroling Document  Paroling Document

Paroling Document

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.