calsfoundation@cals.org

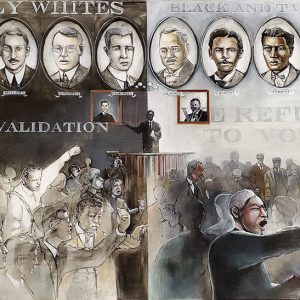

Lily White Republicans

The post-Reconstruction “Redemption” era witnessed Democratic Party forces sweeping Republicans from all branches of state government in Arkansas. Their regime instituted so-called progressive reforms such as the Election Law of 1891, which disenfranchised many African-American voters, who traditionally supported the Republican Party.

From the late 1890s onward, the stigmatized biracial Republican Party remained hopeless underdogs in every statewide electoral contest—and most local ones. Practically the only way Republicans could hope to hold public office remained through federal political patronage appointments. Former governor and state Republican Party leader Powell Clayton controlled the distribution of these federal civil service jobs, which he extended to supporters including African Americans who won his confidence during Reconstruction. By the 1880s, distinct friction had developed between the followers of Clayton and those dissatisfied with him. The latter group challenged him because they differed with his conservative administration of the party or were denied a requested appointment. This anti-Clayton element arose strongest among the younger white Republicans in more urbanized Arkansas communities. They failed to gain much traction until they united in opposition to the benefits African Americans received from him.

In 1888, a clear division in the state Republican Party emerged between Clayton’s biracial coalition, the “Black and Tans,” and these racist opponents, the “Lily Whites.” The latter faction’s unifying ideal became the gradual, “genteel” (that is, tactful and non-violent) elimination of Black Republicans from the party’s governing councils. The Lily Whites declared that the party needed to distance itself from African Americans in order to render it more competitive against Democrats in elections. The institutionalized racism of Jim Crow encouraged the Lily Whites’ activities. This Lily White movement grew in momentum in Republican parties across the former Confederacy and gained evident approval from national party leaders by the early 1900s. The Republican presidential administrations of Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft acted little to address the neutralization of southern Black Republicans in their state party councils and additionally purged many from federal civil service patronage jobs in favor of white candidates.

Clayton and his protégé, Harmon L. Remmel, endeavored to rally enough whites to preserve a Black and Tans majority through the turn of the twentieth century and after. Yet in 1914, the Lily Whites, led by Harmon’s nephew, Augustus Remmel, gained domination over the state party’s powerful central committee. Afterward, Lily Whites surged in number at party assemblies due to the political maneuverings of their leaders-turned-party-executives.

Augustus Remmel and his allies sought to out-maneuver the Black and Tans at the Pulaski County Republican Convention by applying passive-aggressive tactics—ignoring credentials, convening at “whites-only” venues, cramming meetings with their followers, and subjectively enforcing procedural rules. His model spread to other county parties and the state conventions, effectively curtailing African-American delegates and their allies from exercising any influence. The marginalization Lily Whites implemented at the outset of 1920 Republican State Convention held at the Kempner Theater in Little Rock (Pulaski County) prompted the Black and Tans to depart en masse to form a separate convention nearby. This exodus convinced the Lily Whites that they had finally succeeded in their overarching objective. Subsequently, they elected an all-white ticket for state and federal offices and party positions. The Black and Tans boldly ran a gubernatorial candidate, the formerly enslaved public education official Josiah Blount, against the Lily White candidate, Wallace Townsend, and received over eight percent of the vote. Arkansas’s Black and Tan Republicans ran no separate candidates for office in any elections after 1920.

Chairman Remmel ridiculed the actions of the Black and Tan Republicans in 1920, remaining entirely unrepentant for his actions that drove them away. That December, less than two weeks after the election results were finalized, Remmel died suddenly from “hemorrhagic malarial fever.” But his passing precipitated no reconciliation of the racial rift he cultivated in his party.

Nonetheless, the Lily Whites miscalculated in their belief that purging Black Republicans would attract many white (and typically Democratic) voters to their ranks; their party’s gubernatorial candidates performed progressively worse in the succeeding elections. In 1920, Democratic victor Thomas C. McRae won 65 percent of the popular vote, followed by the Republican candidate Wallace Townsend, who received 24 percent, and Blount with 8 percent. In 1922, McRae captured 78 percent in his reelection bid, with the Republican nominee, John W. Grabiel, receiving approximately 22 percent. In 1924, the Democratic candidate, Thomas J. Terral, defeated Grabiel in his second bid by a slightly higher margin.

Harmon L. Remmel quickly replaced his nephew as central committee chairman. In a few years, presumably after tensions abated, he made meek overtures to entice the estranged prominent African Americans back to the party. Though he convinced leading Lily Whites to quietly reverse themselves to permit African Americans as a minuscule, token presence in state party councils, they never recovered anywhere near the levels of participation they recorded prior to 1920.

For additional information:

Dillard, Tom W. “To the Back of the Elephant: Racial Conflict in the Arkansas Republican Party.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 33 (Spring 1974): 3–15.

Gordon, Fon Louise. Caste & Class: The Black Experience in Arkansas, 1880–1920. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1995.

Lewis, Todd. “Race Relations in Arkansas, 1910–1919. PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 1995.

Rector, Charles J. “Lily-White Republicanism: The Pulaski County Experience, 1888–1930.” Pulaski County Historical Review 42 (Spring 1994): 2–18.

Stockley, Grif. Ruled by Race: Black/White Relations in Arkansas from Slavery to the Present. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2009.”

Walton, Hanes, Jr., Sherman C. Puckett, Donald R. Deskins Jr. The African American Electorate A Statistical History. Thousand Oaks, CA: CQ Press, 2012.

Drew Ulrich

Division of Arkansas Heritage, Delta Cultural Center

Politics and Government

Politics and Government Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Black and Tan Republicans

Black and Tan Republicans  Black and Tan Republicans Article

Black and Tan Republicans Article  Lily White Republicans

Lily White Republicans  Augustus Remmel

Augustus Remmel

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.