calsfoundation@cals.org

Levees and Drainage Districts

Reclaiming the swamp and overflow lands in the Mississippi River Delta required draining those lands and building levees to mitigate the inevitable floods that periodically occurred. Without drainage, the land was useless for farming. Early residents realized that once the land was cleared of the timber and drained, the rich alluvial soil would be productive for a variety of crops, especially cotton. Initially, early settlers had attempted to build makeshift barriers to halt the powerful flood waters, but these attempts were ultimately useless. Although the line of levees along the Mississippi River expanded during the nineteenth century, the water always found a weak spot and inundated the region.

In 1879, Congress created the Mississippi River Commission to establish a unified flood control plan. In cooperation with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the commission’s goal was to build higher levees based on previous flood heights and improve their quality. Between 1905 and 1915, the Arkansas General Assembly passed laws to create a program of flood control in Arkansas’s Mississippi River Valley.

Organization of drainage districts required landowners to petition the county courts to place a lien on the lands through a court order. The court order insured that improvement taxes would be paid. Money collected from the taxes paid the principle; it and interest on bonds issued by the drainage district, along with proceeds from the bond sales, were used to build the levees and drainage canals. The drainage districts also had the power to hire deputies to patrol levees to keep sabotage and vandalism at a minimum. Often, the drainage districts received matching funds from the federal government.

Arkansas’s levee/drainage districts were:

- · Chicot District—Chicot County (1883)

- · Clay and Greene District—Clay and Greene counties (1887)

- · Laconia District—Desha and Phillips counties (1891)

- · Red Fork District—Desha County (1891)

- · St. Francis District—Crittenden, Mississippi, Cross, Phillips, Lee, St. Francis, and Poinsett counties (1893)

- Linwood and Auburn District—Lincoln County (1905)

- · Plum Bayou District —Lonoke, Jefferson, and Pulaski counties (1905)

- · District Number 1 of Faulkner County—Faulkner County (1905)

- · French Town District—Jefferson County (1905)

- · Long Prairie District—Lafayette County (1905)

- · Red River District Number 1—Lafayette County (1905)

- · Tucker Lake District—Jefferson County (1905)

Many of these early drainage districts found it both physically and politically difficult to construct adequate levees to halt the overflow of the Mississippi River. Some people believed that building levees interfered with the natural development of the land; hunters, in particular, resented being told to vacate land they had hunted and fished for years and feared that drainage canals would destroy the habitat for animals and fish. Those who lived or ran stock on the islands in the Mississippi River feared that levees would raise the level of the river and flood them out. There were attempts in some areas to cut the levees and sabotage the plans of the drainage districts.

However, the majority of the people of the state benefited from the levee-building efforts of the twelve districts. For example, prior to adequate levees in Mississippi County, approximately five percent of the rich alluvial land was in cultivation and another five percent capable of cultivation. About ninety percent of the county “was regarded as a hopeless permanent mosquito and malaria infested swamp.” After the lands were drained, that swampland was turned into tillable soil, and instances of malaria dropped dramatically; doctors treated in the span of a year what they had previously treated in a week.

It took many years for the levee systems and drainage canals to be successful in keeping the water out. Opposition by many large landowners and the Northern-owned lumber companies, who were averse to paying drainage taxes, hindered levee building for a time. In addition, many of the early levees were poorly constructed and were susceptible to collapse when pounded by violent floods. However, through perseverance and sheer luck, in many cases, the drainage districts became successful and enabled Arkansas to become one of the most productive farming states in the nation.

During the Flood of 1927, the levees failed, and the whole system had to be revamped. Herbert Hoover, then the secretary of commerce, acknowledged that part of the devastation from the flood was due to the “tinkering” of humans: despite unusually heavy rains, it was the levee system itself that resulted in the flood waters being poured into the Mississippi River Valley all at one time, as the tributaries had no room to expand due to the levees.

In the modern era, there has been a great deal of rethinking on the issue of levees and drainage districts. The fertility of the soil surrounding the Mississippi River and its tributaries has, for millennia, depended upon cyclical flooding of rivers. Levees have effectively prevented that flooding for the sake of stability. Modern land draining and clearing equipment, along with intensive farming practices, are slowly exploiting the Delta, one of the richest agricultural regions in the United States, to the point of degradation.

For additional information:

Barry, John M. Rising Tide: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and How It Changed America. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997.

Burns, Jean. “A History of Drainage Control in Arkansas.” Craighead County Historical Quarterly 8 (Winter 1970): 6–11.

Daniel, Pete. Deep’n As It Come: The 1927 Mississippi River Flood. New York: Oxford University Press, 1977.

Deaton, Ron. “A History of Terre Noire Creek and the Ross Drainage District.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 75 (Autumn 2016): 239–254.

Harrison, Robert W., and Walter M. Kollmorgen. “Arkansas Swamp Land Grant of 1850.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 6 (Winter 1947): 369–418.

———. “Socio-Economic History of Cypress Creek Drainage District and Related Districts of Southeast Arkansas” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 7 (Spring 1948): 20–52.

Merritt, Him, and B. Gill Dishongh Sr. “The Levee System of Desha County, Arkansas.” Programs of the Desha County Historical Society 14 (Spring 1988): 7–25.

Phan, Nguyen Danh. “A Multi-Criteria Ranking System for Prioritizing Maintenance of Levee Systems in Arkansas.” MS thesis, University of Arkansas, 2022.

Plum Bayou Levee District Papers. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Sartain, Elliott B. It Didn’t Just Happen. N.p., n.d.

Simpson, S. E. “Origin of Drainage Projects in Mississippi County.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 5 (Autumn 1946): 263–73.

———. “The St. Francis Levee and High Waters on the Mississippi River.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 6 (Winter 1947): 419–29.

Donna Brewer Jackson

Manila, Arkansas

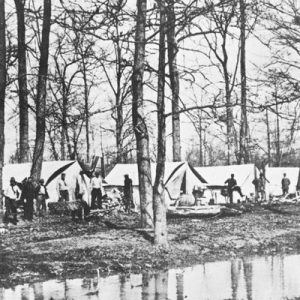

Drainage Survey Camp

Drainage Survey Camp  Drainage Survey Crew

Drainage Survey Crew  Dredge Boat

Dredge Boat  Dredging Project

Dredging Project

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.