calsfoundation@cals.org

Freemasons

aka: Masons

History of Freemasonry

The history of Freemasonry in Arkansas is closely linked to the history of Arkansas. Many of the founders of the state were the leaders and founders of Freemasonry, and the early impact of the fraternity was in education and government. The Grand Lodge established one of the state’s first institutions of higher education, St. Johns’ College, in 1859, and in 1853, it established the second public library in Arkansas; both institutions were in Little Rock (Pulaski County). Many of the state’s early governors, judges, representatives, and senators were members of the fraternity.

Freemasonry has been described as a system of morality, veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols, the goal of which is to take good men and make them better men. It is a fraternity, a gathering of men with a common goal and common beliefs. While not in any sense a religion, it requires of its members a belief in a supreme being and the immortality of the soul. Membership is by a progressive degree system with three degrees: Entered Apprentice, Fellow Craft, and Master Mason. A Master Mason has all the rights and privileges of the organization.

Freemasonry established itself in what would become Arkansas within nine months of Arkansas’s birth as a territory. On December 1, 1819, the Grand Lodge of Kentucky granted a charter to the Masons living in the new territorial capital, Arkansas Post (Arkansas County), to establish Arkansas Lodge UD (under dispensation), with Robert Johnson as the first master of the lodge.

Two of the most ardent early Masons were Robert Crittenden and Andrew Scott. President James Monroe had appointed them as territorial secretary and judge, respectively, in 1819. The two men established the government and laws of the new territory and established the first lodge. The first person made a Master Mason in Arkansas was Colonel James Scull, territorial treasurer, who received his degree on June 17, 1820. When the legislature moved the capital from Arkansas Post to Little Rock in 1821, Arkansas Lodge Number 59 ceased to be a lodge. Lodge 59 surrendered its charter in 1822, and organized Freemasonry in Arkansas was dormant for the next thirteen years.

As Arkansas moved toward statehood, Freemasonry had a rebirth. On November 5, 1835, the Grand Lodge of Tennessee instituted Washington Lodge Number 82 in Fayetteville (Washington County). Soon after statehood was granted, three more lodges were established: in 1837, the Grand Lodge of Louisiana instituted Western Star Number 43 in Little Rock and Morning Star Number 42 at Arkansas Post, and the Grand Lodge of Alabama established Mount Horeb in Washington (Hempstead County).

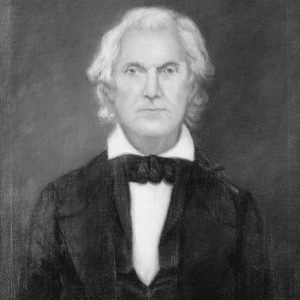

By 1838, there were about 100 Masons in Arkansas’s four lodges. In the government of Freemasons, a lodge must have a charter or authority from a recognized Grand Lodge to work, meet, and initiate new people into the fraternity. In Masonic law, four regularly chartered lodges may unite and establish a Grand Lodge in an area where no other Grand Lodge holds exclusive jurisdiction. This was the case on November 21, 1838, when representatives from the four lodges met in Little Rock and formed the Grand Lodge of Arkansas. The lodges surrendered their charters to the Grand Lodges that had issued them and took new charters from the Grand Lodge of Arkansas. Of the four founding lodges, two remain: Washington Lodge 1 and Western Star Lodge 2. William Gilchrist of Little Rock was elected the first grand master of Masons in Arkansas. Gilchrist served as deputy grand master of the Grand Lodge of Tennessee in 1830. He is buried at Mount Holly Cemetery in Little Rock, where the Grand Lodge erected a monument to his memory.

The first building erected solely for use as a Masonic lodge hall was in Fayetteville. Future governor Archibald Yell donated the land and $100 to Washington Lodge 1 for that purpose in 1839. (The building survived the Civil War when Union troops under Colonel M. LaRue Harrison occupied the city and took the building for his headquarters. It was reported that Harrison and many of his men were made Masons in Washington Lodge 1, hence its being spared destruction when all other public buildings were leveled.)

Freemasonry, like Arkansas, grew and prospered in the next two decades. Masons from every corner of Arkansas established lodges and initiated men until the onset of the Civil War. During the Civil War, the Grand Lodge followed the state’s Confederate government from Little Rock to Washington. Most of the lodges in Arkansas surrendered their charters, their members having gone to war, their buildings occupied or burned, and their treasuries empty. But even this could not extinguish Masonry. Elbert H. English, chief justice of the state’s Confederate Supreme Court, held together the fraternity during those times.

Before the war, Arkansas Freemasons had made two bold moves. In 1853, they established the library of the Grand Lodge of Arkansas with Albert Pike as chairman. It is the second-oldest library in the state. In 1859, they opened St. Johns’ College in Little Rock and educated many of the state’s leaders.

In the decade after the war, Freemasonry was reestablished slowly in every section of Arkansas. By the end of the nineteenth century, there were 12,522 Masons in 442 lodges; the “golden age” of Masonry had begun. In November 1938, Freemasons from all over the state traveled to the Albert Pike Memorial Temple in Little Rock to celebrate their centennial. In 1938, there were 23,641 Master Masons in 434 lodges.

Freemasonry continued its growth and charity work in the twentieth century. The charity endeavors of the Grand Lodge include the laying of the foundation for the Arkansas School for the Blind building; the erection of the Children’s Clinic and Hospital buildings at the Tuberculosis Sanatorium in Booneville (Logan County); the establishment of an orphanage, The Masonic Home, in Batesville (Independence County); the construction of the occupational therapy building at Children’s Hospital in Little Rock; and the granting of hundreds of college scholarships.

Since territorial days, many leaders of business, government, law, medicine, religion, and education have been Masons. Two—Albert Pike and Fay Hempstead—had a national impact on the fraternity. Pike was a newspaper publisher, lawyer, Confederate general, and justice in Arkansas, and he invigorated and led the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry in the United States for thirty-two years. Hempstead wrote Arkansas’s first school history and served as the grand secretary of the Grand Lodge of Arkansas from 1881 to 1933. In 1908, he became the third poet laureate of Freemasonry, following Robert Burns of Scotland and Robert Morris of Kentucky.

Modern Freemasonry

Arkansas Masonic membership in 2005 was 17,699 members in 293 lodges. The fraternity practices the tenets of friendship, morality, and brotherly love. The ruling body of Arkansas Masons is the Grand Lodge of Arkansas in the Albert Pike Masonic Memorial Temple in Little Rock.

The history of Freemasonry in Arkansas is still being written. In the twentieth century, the Masons of Arkansas continued their tradition of charity. From the early 1950s to the 1990s, the Arkansas Children’s Hospital was the focus of their work. One of their projects was the contribution of funds to build the hospital’s occupational therapy building. In 1997, the Arkansas Association of Sheltered Workshops became the official charity of the Grand Lodge. A brief survey of notable Arkansans who have been Masons includes Governor George Donaghey; builder and philanthropist H. Tyndall Dickinson; businessman Charles E. Rosenbaum, who was also a builder of great Masonic temples; businessman and education advocate Joshua Shepherd; pastor W. O. Vaught Jr.; physician and medical educator Francis Vinsonhaler; Congressman Wilber Mills; Congressman John Paul Hammerschmidt; Governor Orval Faubus; Governor Sidney McMath; attorney and banker William Bowen; and businessman and developer Doyle Rogers.

The mid-1960s saw a drastic change in how society views the relevance and importance of social clubs and fraternal groups, and membership in Masonic orders began a gradual decline. For the most part, lodges in rural and small town Arkansas have merged together, whereas lodges in larger towns and metropolitan areas continue their mission but with fewer members.

African American Freemasonry

Prince Hall Masonry or “Black Masonry” came to Arkansas in 1869 when the Reverend Moses A. Dickson, an African Methodist Episcopal (AME) preacher, arrived in Helena (Phillips County). The first three Prince Hall lodges in Arkansas were the Alexander Lodge in Helena, the Jeptha Lodge in Little Rock, and the Widow’s Son Lodge in Fort Smith (Sebastian County). These three lodges came together in 1873 to form the Most Worshipful Grand Lodge (Colored) of Free and Accepted Masons in Arkansas, with the Reverend William H. Grey as their first grand master. This Grand Lodge erected a Masonic Temple in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) in 1909. Under Grand Master J. H. Harrison, Prince Hall Masonry’s membership grew to almost 22,000 prior to the Depression. In 2006, there were 3,500 members in eighty-seven lodges.

For additional information:

Bullock, Steven C. Revolutionary Brotherhood. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

Jacob, Margaret C. The Origins of Freemasonry. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005.

Jones, Adrienne A. “Black Organizing through Fraternal Orders: Black Mobilization and White Backlash.” In The Elaine Massacre and Arkansas: A Century of Atrocity and Resistance, 1819–1919, edited by Guy Lancaster. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2018.

Kidd, F. W. Arkansas Freemasonry. Little Rock: 1908.

Library of the Grand Lodge of Arkansas. They Made a Difference…Arkansas’ Freemasons. Richmond, VA: Macoy Publishing & Masonic Supply Co., Inc., 2003.

Talbert, Mark. American Freemasons. New York: New York University Press, 2005.

Dick E. Browning

Maumelle, Arkansas

Shriners

Shriners United Sons of Ham of America

United Sons of Ham of America Albert Pike Memorial Temple

Albert Pike Memorial Temple  Albert Pike Temple

Albert Pike Temple  Camden Masonic Lodge

Camden Masonic Lodge  Chidester Masonic Lodge

Chidester Masonic Lodge  Robert Crittenden

Robert Crittenden  Damascus Masons

Damascus Masons  George Donaghey

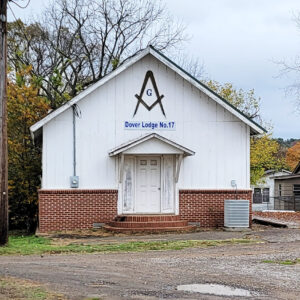

George Donaghey  Dover Masons

Dover Masons  Dover Masonic Lodge

Dover Masonic Lodge  El Paso Masonic Lodge

El Paso Masonic Lodge  Elbert English

Elbert English  Orval Faubus

Orval Faubus  Freemason Monument

Freemason Monument  Galley Rock Masonic Marker

Galley Rock Masonic Marker  Greenbrier Masons

Greenbrier Masons  John Paul Hammerschmidt

John Paul Hammerschmidt  Fay Hempstead

Fay Hempstead  Kensett Masonic Lodge

Kensett Masonic Lodge  Masonic Building

Masonic Building  Masonic Lodge 426

Masonic Lodge 426  Masonic Temple

Masonic Temple  McRae Masonic Lodge

McRae Masonic Lodge  Wilbur D. Mills

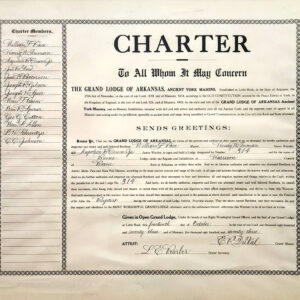

Wilbur D. Mills  Lodge 314 Charter

Lodge 314 Charter  Paris Masonic Lodge

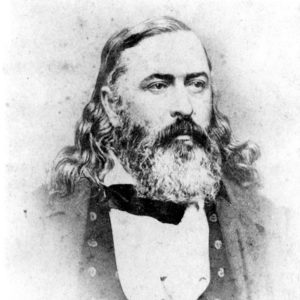

Paris Masonic Lodge  Albert Pike

Albert Pike  Plumerville Masons

Plumerville Masons  Romance Masons

Romance Masons  Andrew Scott

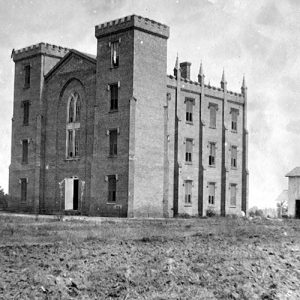

Andrew Scott  St. Johns' College

St. Johns' College  Whittington Lodge

Whittington Lodge  Archibald Yell

Archibald Yell

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.