calsfoundation@cals.org

First Arkansas Volunteer Infantry Regiment (CS)

As secession loomed in the spring of 1861, thousands of Arkansas men enrolled in volunteer companies and offered their services to the Confederacy. Ten such companies—raised in Union, Clark, Ouachita, Jefferson, Saline, Jackson, Arkansas, and Drew counties—were organized as the First Arkansas Volunteer Infantry Regiment and were transferred to Lynchburg, Virginia. After Arkansas seceded from the Union on May 6, 1861, the 905 men in the First Arkansas mustered into service on May 19. James Fleming Fagan, the captain of the Saline County Volunteers, was elected to serve as colonel of the regiment.

The First Arkansas was present but did not see action at the First Battle of Manassas on July 21, 1861. The regiment remained in Virginia through the winter, with the majority of the men reenlisting with the promise of a fifty-dollar bonus and a furlough to Arkansas. Following their visits home, the men of the First Arkansas were ordered to rendezvous in Memphis, Tennessee, on March 15, 1862. They served in the western theater for the duration of the war.

The regiment became part of the Army of Mississippi, stationed at Corinth, and marched north to attack Ulysses S. Grant’s Union army at Pittsburg Landing on the Tennessee River. The First Arkansas suffered heavy casualties attacking a Federal strongpoint remembered as “the Hornet’s Nest” during the April 6, 1862, Battle of Shiloh, with Colonel Fagan reporting that they “endured a murderous fire until endurance ceased to be a virtue.” The regiment was in the thick of the fighting the next day as Grant’s army counterattacked, and it fell back to Mississippi after suffering a total of 364 casualties.

The First Arkansas next saw action as part of a provisional brigade, led by Fagan, which attacked a Union force at Farmington, Mississippi, on May 9, 1862, suffering one dead and three wounded while capturing five soldiers. Abandoning Corinth on May 29, the regiment marched to Tupelo. Fagan left the regiment to return to cavalry duty in Arkansas, and twenty-three-year-old John W. Colquitt of Monticello (Drew County) became the new colonel of the First Arkansas.

Now in Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee, the First transferred to Chattanooga and marched north on August 28 to participate in the invasion of Kentucky. The regiment fought at Perryville on October 8 and retreated to Knoxville with the rest of the army. The First Arkansas was transferred to Brigadier General Lucius Polk’s brigade in Major General Patrick Cleburne’s division in early December and moved to new positions at Murfreesboro, Tennessee. On December 31, 1862, the First Arkansas fought in the opening day of the Battle of Stone’s River, capturing a four-gun artillery battery, and fell back to Tullahoma on January 3, 1863, having lost eleven dead, ninety wounded, and one missing in the fighting at Murfreesboro.

The army moved into fortifications between Murfreesboro and Tullahoma, protecting the strategic rail center at Chattanooga. In June 1863, Union general William S. Rosecrans executed a series of maneuvers that forced Bragg to fall back to Chattanooga; Bragg then retreated into the mountains of north Georgia on September 8. On September 19, Bragg attacked Rosecrans on Chickamauga Creek, with the First Arkansas moving forward into heavy fire as night fell over the battlefield. The Arkansans attacked again the next day, driving the Federals from their breastworks as part of a victory that saw Rosecrans’s army retreat to Chattanooga. The First Arkansas, which went into battle with 430 men, had thirteen killed, 180 wounded, and one missing at Chickamauga.

Bragg’s army besieged the Federals at Chattanooga but was driven from the high ground around the city on November 25. Cleburne’s division of 4,175 men formed a line at Ringgold Gap, Georgia, on November 27, and the First Arkansas was prominent in the fighting that stopped a 12,300-man Union corps and allowed the rest of the Confederate army to escape. Cleburne wrote of the First, which captured two stands of colors during the battle: “In a fight where all fought nobly I feel it my duty to particularly compliment this regiment for its courage and constancy.”

The Army of Tennessee went into winter quarters at Tunnel Hill, Georgia, and Gen. Joseph E. Johnston replaced Bragg as commander. As spring campaigning began, the 55,000 Confederates faced about 100,000 Federals in the combined armies of the Cumberland, the Tennessee, and the Ohio under the command of William Tecumseh Sherman. Johnston attempted to hold Sherman by fortifying several positions in the north Georgia mountains, but the Federals used their superior numbers to repeatedly flank the Confederates from their fortifications. During this period, the First Arkansas was consolidated with the Fifteenth Arkansas Infantry, another regiment depleted by heavy casualties. The regiment became part of Daniel Govan’s brigade after Lucius Polk lost a leg to a Union artillery shell.

At Kennesaw Mountain on June 27, 1864, Sherman attempted a frontal assault against Cleburne’s division. The Union troops suffered heavy casualties, and, at the height of the fighting, dry leaves and brush caught fire. As the flames approached the helpless Federal wounded in front of the First Arkansas Infantry Regiment, Lieutenant Colonel William H. Martin of the First called for a ceasefire; Rebels and Yankees both raced from their lines to rescue the wounded from burning to death.

On July 17, Confederate leaders replaced Johnston with John Bell Hood. The aggressive Hood attacked the Federal troops as they closed in on Atlanta, and the First and Fifteenth Arkansas won laurels on July 22 for capturing the entire Sixteenth Iowa Infantry Regiment and eight artillery pieces. Following the Battle of Atlanta, Sherman sent five corps south of the Georgia capital to cut the railroad lines at Jonesboro. In fighting there on September 1, Govan and 600 men of his brigade were overwhelmed and captured. The First and Fifteenth Arkansas lost its battle flag to the Fourteenth Michigan Infantry Regiment in this battle, and Hood abandoned Atlanta that night.

Govan and his men were among 2,000 men freed in a special exchange on September 9, and they were with Hood when he led the Army of Tennessee north from Alabama to attack Nashville. At Franklin, he ordered his army to form a line two and a half miles wide and march a mile and a half across open ground to attack Federal fortifications. The Confederates lost 6,500 of the 17,500 men who made the attack; among the dead were six generals, including Cleburne. Casualties in the First and Fifteenth Arkansas were so high that its ten companies were consolidated into six.

The depleted regiment fought in the December 15–16 Battle of Nashville and retreated to Tupelo, Mississippi. In March 1865, survivors of the Army of Tennessee, including the First and Fifteenth Arkansas, were transported to South Carolina to oppose Sherman’s Union army. The regiment fought at Bentonville, North Carolina, on March 19 and was consolidated with ten other depleted Arkansas regiments after falling back to Smithfield. The survivors of the consolidated regiment were among the 2,358 men who had served in Cleburne’s division who surrendered at Greensboro, North Carolina, on April 26, 1865.

For additional information:

Christ, Mark K., ed. Getting Used to Being Shot At: The Spence Family Civil War Letters. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2002.

Hammock, John C. With Honor Untarnished: The Story of the First Arkansas Infantry Regiment, Confederate States Army. Little Rock: Pioneer Press, 1961.

Sutherland, Daniel E., ed. Reminiscences of a Private: William E. Bevens of the First Arkansas Infantry, C.S.A. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1992.

Mark K. Christ

Little Rock, Arkansas

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874 Military

Military Second Arkansas Infantry Battalion (CS)

Second Arkansas Infantry Battalion (CS) Shoppach House

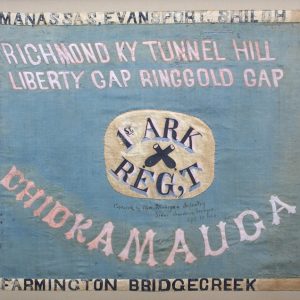

Shoppach House 1st and 15th Infantry Regiment Flag

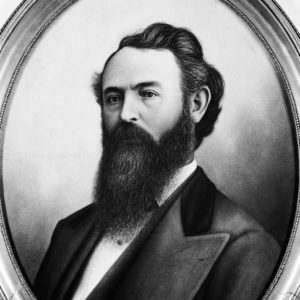

1st and 15th Infantry Regiment Flag  James Fagan

James Fagan  The Hornet's Nest

The Hornet's Nest

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.