calsfoundation@cals.org

Equal Rights Amendment (ERA)

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) is a proposed Amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would guarantee equal rights for women. Sent to the states in the spring of 1972, it fell short of the required ratification by three-quarters—thirty-eight—of the states. Arkansas was one of the fifteen states that did not ratify the amendment by the deadline established in the congressional directive sending the amendment to the states. However, it has periodically become the object of renewed efforts at ratification.

The amendment, which was passed by both houses of the U.S. Congress in 1972 and then sent on to the states for ratification, states:

Section 1: Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any state on account of sex.

Section 2: The Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

Section 3. This amendment shall take effect two years after the date of ratification.

The ERA was first introduced in Congress in 1923, and after decades of rejection but with the support of the burgeoning women’s rights movement of the 1960s, it was overwhelmingly passed by both houses of Congress in early 1972. On March 22, 1972, it was put before the states for ratification, with Congress requiring that ratification be achieved within a seven-year period. The process began quickly, with Hawaii ratifying the amendment that day. Seven other states had completed the process by the end of March, and they were joined by an additional fourteen by the end of the year. Eight more states joined the list in 1973, but conservatives, led by activist Phyllis Schlafly, mounted a countermovement, and progress soon slowed to a standstill, while the issue of whether a state that had ratified the amendment could rescind its original decision came under discussion. Ultimately, ratification was not achieved by the end of the seven-year period, and while Congress added an additional three years, at the end of that period, June 30, 1982, ratification of the amendment remained short of the necessary thirty-eight states, while the question of whether a state could rescind an earlier affirmative vote remained unresolved.

From the beginning, the outlook for ratification in conservative Arkansas was not very good. Indeed, in the end, not only was Arkansas one of the original fifteen states that failed to ratify the proposed amendment, but advocates were never able to get a vote of even one full house on the proposal. Each effort to secure ratification met defeat at the committee level.

The initial effort in the early 1970s demonstrated the deep divide in the state’s politics. Arkansas had never been a hotbed for women’s rights, but the ratification campaign did much to energize the state’s limited women’s movement. ERArkansas was created to lobby on behalf of the amendment, and the group, started in 1972 and led by Alice Glover of Little Rock (Pulaski County) and Margie Ann Chapman of Quitman (Cleburne and Faulkner counties), lobbied state legislators and ran an ad campaign in the effort to secure support for ratification. Pat Johnson organized an Arkansas chapter of the National Organization for Women (NOW) in March 1974; the state chapter and local chapters in Little Rock, Fayetteville (Washington County), Hot Springs (Garland County), and Arkadelphia (Clark County) were also active in the ratification effort. Meanwhile, Dale Bumpers, who served as governor from 1971 to 1975 before being elected to the U.S. Senate, offered his support, noting that most of the nation’s working women were in the workforce out of need, and as a result, equal rights and equal opportunity were very real, life-altering concepts, and not merely chic political slogans. Even the state’s major churches were split, with Methodists being generally and often actively supportive, while the Baptist churches generally opposed the effort.

The Arkansas General Assembly first considered the issue of ratification in 1975, three years after it had been sent to the states. A highlight of this push was the February 14, 1975, debate between ERA supporter Diane Kincaid (later Blair), a respected political scientist at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville, who had served as chair of the Governor’s Commission on the Status of Women, and Phyllis Schlafly, an Illinois housewife and one-time candidate for Congress who had worked in the 1964 presidential campaign of Republican Barry Goldwater. As the early ratification votes piled up, Schlafly had emerged as the leading national spokesperson for anti-ratification forces, as she and her organization, STOP ERA, raised concerns about women being drafted or losing their alimony in divorce proceedings; they also alleged that the amendment would mean the end of single-sex bathrooms. The Arkansas debate raised the profile of the issue, but while observers gave Kincaid high marks for her advocacy, it appeared to have little impact, as the ratification proposal remained mired in the State Agencies and Governmental Affairs Committee through the end of that legislative session.

Another attempt was made in 1977, but this one, led by progressive Republican representative Carolyn Pollan of Fort Smith (Sebastian County), again came up short. However, Pollan’s proposal did gain passage, on a voice vote, by the State Agencies and Governmental Affairs Committee. But supporters sought to bring the proposal straight to the floor of the full House, opponents were able to get it referred to the Rules Committee, where it remained for the rest of the legislative session.

With time running out, the state’s NOW branch redoubled its efforts in the early 1980s. However, it was met by the advent of a new opposition group, Family Life and God (FLAG), whose efforts led Arkansas Senate president pro tempore Ben Allen to declare in 1981 that “the chances are slim or none” that the Arkansas legislature would ratify the amendment. And when the June 30, 1982, deadline arrived, he was right—not only in terms of Arkansas but across the nation.

That was where things stood until a 1997 law review article—citing the adoption of the Twenty-Seventh Amendment in 1992, some 203 years after it was proposed—argued that the ERA was still alive. Consequently, another round of efforts was undertaken, with the focus being placed on the fifteen states that had failed to ratify on the first attempt. With this new impetus, Arkansas’s pro-ERA advocates renewed their efforts. Leading the effort was State Representative Lindley Smith who, along with State Senator Sue Madison (both of them from Fayetteville), introduced resolutions in the Arkansas House and Senate, respectively, in March 2005, calling for ratification. However, as it became clear that both bills were destined to wallow in committee, the authors withdrew their bills. Despite Smith noting that many people greeted her efforts with surprise, saying that they thought the ERA was already in the U.S. Constitution, subsequent efforts in 2007, 2009, 2013, and 2017 all met similar fates, dying in committee as the session adjourned. Efforts sponsored by State Senator Joyce Elliott and State Representative Warwick Sabin, both of Little Rock, came to a close on May 1, 2017, while Senator Elliott led another unsuccessful attempt in 2019, but as long as the debate over the amendment’s viability continues, Arkansas supporters expect to continue the effort in future legislative sessions.

For additional information:

Levy, Gabrielle. “Equal Rights Amendment, Left for Dead in 1982, Gets New Life in the #MeToo Era.” U.S. News & World Report, June 4, 2018. Online at https://www.usnews.com/news/national-news/articles/2018-06-04/equal-rights-amendment-left-for-dead-in-1982-gets-new-life-in-the-metoo-era (accessed February 20, 2024).

Parry, Janine A. “‘What Women Wanted’: Arkansas’s Women’s Commission and the ERA.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 59 (Autumn 2000): 265–298.

Stewart, Emily. “The Equal Rights Amendment’s Surprise Comeback, Explained,” Vox, May 31, 2018. https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2018/5/31/17414630/equal-rights-amendment-metoo-illinois (accessed February 20, 2024).

William H. Pruden III

Ravenscroft School

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022 Law

Law Politics and Government

Politics and Government Joyce Elliott

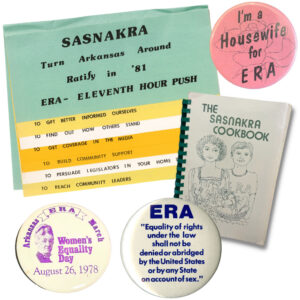

Joyce Elliott  ERA Ephemera

ERA Ephemera  Sue Madison

Sue Madison

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.