calsfoundation@cals.org

Engagement at Jenkins' Ferry

| Location: | Grant County |

| Campaign: | Camden Expedition |

| Dates: | April 29–30, 1864 |

| Principal Commanders: | Major General Frederick Steele, Brigadier General Frederick Salomon (US); Lieutenant General Edmund Kirby Smith, Major General Sterling Price, Major General John Sappington Marmaduke (CS) |

| Forces Engaged: | Salomon’s Third Division and elements of Brigadier General John M. Thayer’s Frontier Division (US); Army of Arkansas (CS) |

| Estimated Casualties: | 521 (US); 443 (CS) |

| Result: | Union victory |

The Engagement at Jenkins’ Ferry occurred April 29–30, 1864, when Confederates caught the Federal army retreating from Camden (Ouachita County) near the Saline River. After intense combat, the Union troops crossed the river and returned to Little Rock (Pulaski County).

The Camden Expedition had not gone well for Major General Frederick Steele. Poor logistical conditions and an increasing Confederate presence in southwestern Arkansas led to the abandonment of his planned invasion route toward Shreveport, Louisiana. Shifting eastward and capturing Camden, Steele hoped to find the logistical support necessary to continue his movement toward northwestern Louisiana. From Camden, Steele dispatched troops to obtain supplies. On April 18, 1864, the first foray resulted in the disastrous loss of some 301 combatants and 198 wagons at the Engagement at Poison Spring. A second deployment of troops to obtain supplies eastward toward Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) ended in a second disaster for Steele, with the loss of another 1,800 combatants and 240 wagons as the entire force capitulated at the Action at Marks’ Mills on April 25, 1864.

The loss of men, stock, and wagons at Poison Spring and Marks’ Mills placed Union Major General Frederick Steele in a precarious position. With few supplies and increasing Confederate numbers due to the arrival of Lieutenant General Edmund Kirby Smith’s command from Louisiana, Steele’s position became untenable. During the night on April 26, Union troops quietly withdrew across the Ouachita River. The successful maneuver did not attract the attention of the Confederates for several hours.

On April 29, Steele’s column arrived at the Saline River. Without delay, engineers began building pontoons across the swollen river, and soldiers began constructing crude battlements. Confederate Brigadier General John Sappington Marmaduke’s troops arrived and began skirmishing with the Federal rear guard of Brigadier General Frederick Salomon’s Division, stopping as darkness fell.

At daylight on April 30, Marmaduke reengaged Salomon’s men but made little headway. Reinforcements arrived under Confederate Major General Sterling Price, who quickly sent Brigadier General Thomas James Churchill’s division into the fray. As the Confederates approached, the ground sloped toward the Federal position in the swampy river bottoms. Salomon’s men had anchored their right flank to a flooded creek and their left in dense, swampy woodland, leaving only small areas for unobstructed maneuvering. As a result, Churchill had to feed his brigades into the fight piecemeal, which worked toward the Union advantage. In good position but outnumbered, Salomon received reinforcements from Brigadier General John M. Thayer’s Frontier Division, including the Second Kansas Colored Infantry, and blunted the Confederate attack.

Wishing to regain momentum, Confederate Brigadier General Mosby M. Parsons’s division deployed forward to assist Churchill. Parsons split his command to fill gaps in the lines, but the advance was ineffectual. Artillery seeking to shell key Federal positions exposed the troops to assault and capture by the Second Kansas Colored Infantry and Twenty-ninth Iowa. During the assault, troops from the Second Kansas bayoneted several surrendering Confederates in retaliation for the brutal murders of surrendering and wounded African Americans from the First Kansas Colored Infantry Regiment during and after the Engagement at Poison Spring. Another strong-willed assault on Parsons’s men by the Fortieth Iowa and the Twenty-seventh Wisconsin reversed the Confederate counterattack. As the Confederate advance fractured, Confederate Major General John G. Walker’s division arrived, deploying forward in hopes of reversing it; however, Walker failed. The overall Confederate attack was called off around 12:30 p.m., ending the engagement.

After conferring with Steele, Salomon moved his men across the river to safety. Union troops destroyed what could not be easily carried, including the pontoon bridge, and continued marching to Little Rock. The Confederates turned to gathering the wounded and reforming their shattered ranks. Several mutilated bodies of Confederate soldiers were discovered near the engagement area of the Second Kansas.

The Confederates claimed losses of eighty-six killed, 356 wounded, and one missing, and the Federals claimed sixty-three killed, 413 wounded, and forty-five missing, but most historians think the numbers were greater because some units did not file official returns. Brigadier General Samuel Allen Rice was wounded in the foot by a bullet fired during the engagement and died several weeks later as a result of this wound.

A small area near Jenkins’ Ferry is preserved as the Jenkins Ferry Battleground State Park near Sheridan (Grant County).

For additional information:

Baker, William D. The Camden Expedition of 1864. Little Rock: Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, 1993.

Bearss, Edwin C. Steele’s Retreat from Camden and the Battle of Jenkins’ Ferry. Little Rock: Arkansas Civil War Centennial Commission, 1967.

Christ, Mark K., ed. Rugged and Sublime: The Civil War in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994.

Urwin, Gregory J.W. “We Cannot Treat Negroes . . . as Prisoners of War: Racial Atrocities and Reprisals in Civil War Arkansas.” Civil War History 42 (September 1996): 193–210.

Derek Allen Clements

Pocahontas, Arkansas

Civil War Events Map

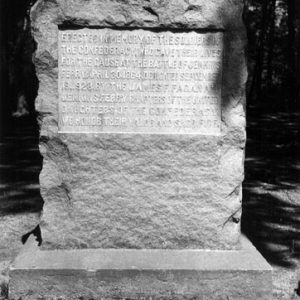

Civil War Events Map  Engagement at Jenkins' Ferry Monument

Engagement at Jenkins' Ferry Monument  Engagement at Jenkins' Ferry Monument

Engagement at Jenkins' Ferry Monument  Jenkins Ferry Battleground State Park Marker

Jenkins Ferry Battleground State Park Marker  Jenkins Ferry Entrance

Jenkins Ferry Entrance  Jenkins' Ferry State Park

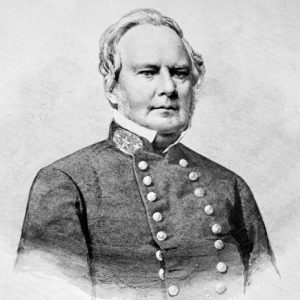

Jenkins' Ferry State Park  Sterling Price

Sterling Price  Friedrich Salomon

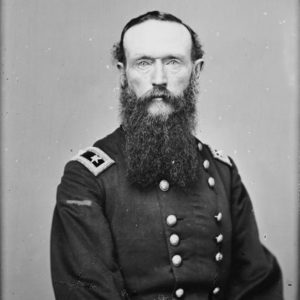

Friedrich Salomon  Frederick Steele

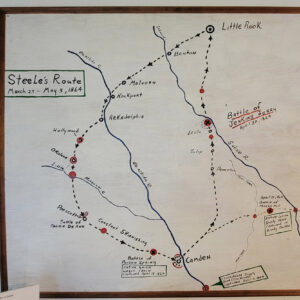

Frederick Steele  Steele's Routes

Steele's Routes

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.