calsfoundation@cals.org

Baptists

Baptists make up the largest Protestant Christian group in Arkansas, characterized by the practice of baptism, usually by immersion, on profession of faith in Jesus Christ. They exhibit great diversity in customs, but most Baptists have congregational polity combined with voluntary interconnection of congregations. They also emphasize autonomy (self-governance) of congregations, associations, and conventions. Leading Baptist groups in Arkansas are the Arkansas Baptist State Convention (Southern Baptist), National Baptist Convention, U.S.A., Inc., National Baptist Convention of America, and American Baptist Association.

Baptist Denominations

Southern Baptists are members of congregations affiliated with the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC), which formed in 1845 in a split over slavery. (Anti-slavery Baptists, mostly from the North, objected to the practice of Baptist missionaries taking their slaves with them to the mission field. Those objecting said that the practice went against the notion that all are equal before Christ.) Unlike the main bodies of Methodists and Presbyterians, who also split before the Civil War, the main denominations of Baptists in the North and South have not reunited. There has always been a strong strain of Calvinism among Baptists, and many Calvinist doctrines have made a resurgence, especially in the SBC. American Baptists are members of congregations affiliated with what used to be called the Northern Baptist Convention, which resulted from the slavery-related split. There are relatively small numbers of American Baptists in the South, mostly in the Southeast, the Carolinas, and Virginia. American Baptists in the South tend to be African American. The National Baptist Convention was formed in 1886 by African American Baptists who had a special desire to send missionaries to Africa. It merged with two other groups in 1895. Its first president after that merger was Elias Camp Morris, from Little Rock (Pulaski County). Several smaller black Baptist groups use the word “National,” but the NBC is by far the largest.

The following smaller groups consist of congregations with varying degrees of association with broader judicatories. Because of their often-intense congregationalism, congregations in the following categories vary in fine points of doctrine, with some variance even within congregations. Free Will Baptists reject a traditional Calvinist position called perseverance of the saints, which Baptists have articulated using the catch-phrase “once saved, always saved,” meaning that one who has had a true conversion experience is incapable of falling from grace. As they see it, people are not predestined for heaven or hell, but they get there because they have chosen to accept Christ’s sacrifice as redemptive of their own spirit. General Baptists also reject a Calvinist position called limited atonement, related to the doctrine of predestination, holding that Christ’s sacrifice is efficacious only for the elect or chosen. This limited view is held by Particular Baptists. Primitive Baptists, sometimes called Hard Shell, emerged in early-nineteenth-century arguments over the appropriateness of having missionary societies. Their use of the word “Primitive” owes to their desire to follow first-century Christian practice (before institutionalization among Christians corrupted the body of believers, as they see it). Although they trace the origin of their beliefs to the New Testament and the times in which it arose, as do many Baptist groups, they admire Calvin’s ideas on predestination. Neither that nor their objection to large-scale missionary organizations, however, keep them from evangelizing.

A hugely important group for Arkansas is the Landmark Baptists, who are fairly numerous in the state, as they are in Tennessee and Texas. They split from Southern Baptists before the Civil War over disputes about having “non-baptized” ministers preach in Baptist churches (i.e., ministers from other denominations, “non-baptized” meaning unimmersed). They coalesced around three ideas: Baptists have been in existence from the time of the New Testament, the local Baptist congregation is the only true church, and those most fervently protecting this belief will be most honored in heaven. They reject any baptism outside of Landmark Baptist auspices, even immersion by Churches of Christ, the Disciples of Christ, or even non–Landmark Baptist congregations. They do not offer communion to anyone outside their individual congregation, even other Landmark Baptists. They are strong supporters of evangelism, however. In fact, many Landmark Baptist congregations also use the word “missionary” in their names.

Beginnings

Baptists entered Arkansas in the early 1800s in the wave of immigrants moving west, but they left few traces until Benjamin Clark and Jesse James organized the first Baptist church in 1818 in Missouri Territory on the Fourche-a-Thomas River in what is now northeast Arkansas. By 1836, when Arkansas attained statehood, they had planted about forty churches and started three or four associations—groups of churches cooperating with one another in education, mission work, and discipline. The strongly evangelistic Baptist constituency grew more rapidly than the general population between 1836 and 1860, from only 810 members in 1840 to 11,341 in 1860, averaging twenty-nine percent to the state’s 16.5 percent growth. In 1860, Baptists also reported 321 churches and sixteen associations. Like their counterparts in other Southern states, Baptists formed a state convention in 1848 to foster missions and education. The work of Baptists north of the Arkansas River led to the creation of two other regional bodies in 1850—the White River Arkansas Baptist Convention and the General Association of Eastern Arkansas—but both folded in the financial panic of 1857.

Civil War and Reconstruction Era

The Civil War and Reconstruction (1861–1874) proved bleak for Baptists and other denominations. Although many churches continued to function during the war, many others had to close, and few associations met. The war siphoned off much of their leadership. The Arkansas Baptist State Convention did not meet between 1861 and 1867. The Arkansas Baptist, a journal begun in 1858 by the convention, ceased publication. Some Arkansas churches still used literature published by the American Baptist Publication Society, which did not condone slavery. From 1868 on, the Southern Baptist Convention moved decisively to make the split permanent. Thereafter, Arkansas Baptists moved increasingly into the Southern Baptist Convention.

Between 1865 and 1870, Baptists barely recouped losses suffered during the war. They lost many members or associate members (those not having the right to vote in church meetings) as African Americans, newly emancipated, formed their own churches. The situation did not improve markedly until about 1875, when immigrants began pouring into the state. Whereas Arkansas’s 1870 population (484,471) barely surpassed that of 1860 (435,470), the 1880 population grew to 806,525. From 1871 to 1880, the number of Baptists increased from 36,040 to 52,798, and the number of churches went from 648 to 1,118. Many immigrants were Baptists, but the rapid growth was chiefly a consequence of energetic evangelism. By then, too, the white Baptist constituency had begun to mature as Arkansas matured. Alongside rough, “hard-shell,” backwoods Baptists were college graduates and people of refinement who could take prominent places in Arkansas society. Such people placed importance on organized effort, education, and a properly paid clergy in ways their forebears could not. In the next phase of their history, while the upward mobility proved fortuitous, it also opened a cleft between the new and old breeds of Baptists.

Growth and Division, 1881–1901

Between 1881 and 1900, both white and black Baptists experienced significant growth. The state paper was resuscitated in 1881 as the Arkansas Evangel (renamed in 1933 as the Arkansas Baptist). In 1881, the Arkansas Baptist State Convention reported 870 churches, thirty-eight associations, and 35,997 members; in 1900, it had 1,321 churches, forty-seven associations, and 71,419 members. In 1881, black Baptists did not reveal the number of churches but listed nine associations and 17,194 members; in 1900, they claimed 868 churches, thirty associations, and 59,033 members. White and black relations were tenuous in this period, but leaders in the two groups made efforts to improve them. In 1883, white Baptists offered modest support for the founding of Arkansas Baptist College, a black school in Little Rock, and contributed small amounts annually to its upkeep. The founding of this college preceded establishment of the first white Baptist college, Ouachita Baptist College (now Ouachita Baptist University) in Arkadelphia (Clark County) by three years and Central Female College (now Central Baptist College) at Conway (Faulkner County) by ten years.

This period raised early signs of the rift that tore apart the Arkansas Baptist State Convention, associations, and churches at the turn of the twentieth century. Many rural Baptists were ill-prepared to understand the development of church life along lines of contemporary corporations as this prevailing social model increasingly imposed itself on Baptist life connected with the Arkansas Baptist State Convention. They listened sympathetically to anti-organizational movements fostered by Alexander Campbell, Daniel Parker, John Taylor, and especially the father of Landmarkism, James Robinson Graves. Although not anti-organizational at the outset, the Landmark movement, with its insistence on the local church as the only expression of church and its refusal to acknowledge the validity of other Christian groups, increasingly veered in that direction. Leading the corporatist advance in society and church was James P. Eagle, governor from 1889 to 1893 and president of the state convention for all but two years between 1881 and 1903. Farmers feared that the governor listened too much to “big business.” The anti-business group found a champion in Jeff Davis, a “hard-shell” Baptist whom they elected attorney general, then governor, and finally U.S. senator. Whereas Eagle represented the educated, progressive, genteel element that grasped the importance of institutional development, Davis, a native of the Ozark regions, stood for the poorly educated, reactionary, backwoods element that could not understand why churches needed costly structures beyond the local congregation. The split came in 1901 under an Eagle presidency.

Ben M. Bogard, a newcomer to Arkansas, and W. A. Clark, disgruntled at being passed over for the position of corresponding secretary of the convention, led the attack on the system. A disaffected faction gathered on April 10–11, 1902, in Little Rock to form the General Association of Arkansas Baptists, which later took the names American Baptist Association and Missionary Baptist Association. The association attracted strong support among district associations, where the issue of structures had brewed a long time. Almost half voted to cooperate with the General Association in mission work, about a fourth to continue cooperation with the state convention, and the rest to remain neutral. The question of affiliation agitated for years, but the tide began to turn in favor of the state convention by the mid-1920s, as it, aided by the Southern Baptist Convention, proved more capable of assisting associations and churches than the General Association.

Baptists as Competitors and Survivors, 1901–1950

Despite the controversy, Baptists continued to grow numerically between 1901 and 1926. In 1922, Baptists claimed almost as many members as other denominations combined. Ten Baptist groups reported 263,251 members, compared with 195,000 reported by seven Methodist groups, 40,000 by Churches of Christ and Disciples, 25,500 by five Presbyterian groups, and 24,000 by Roman Catholics. Of the Baptists, Southern Baptists had 118,316, General Association Baptists 35,500, Black Baptists 97,500, and the seven other bodies 11,935. The state convention lost many churches and members to the General Association again between 1921 and 1926, but it remained the strongest body in the state.

After this slump, the number of Baptists affiliated with the Southern Baptist Convention—boosted especially by a unified fundraising method, originally the 75 Million Campaign and subsequently the Cooperative Program—grew steadily despite the effects of the Great Depression sandwiched between two world wars. From 108,860 members in 827 churches in 1930, they multiplied to 239,049 members in 1,041 churches in 1950. The Depression plunged churches in Arkansas into an economic crisis, which lasted until World War II. Churches, associations, and the Arkansas Baptist State Convention scrambled in many directions to pay off a huge indebtedness, which post–World War I fundraising success had encouraged. Some Baptist institutions, such as Mountain Home College, folded. Others—such as Ouachita College, Central College, and Bottoms Orphanage—barely survived. The state convention did not meet in 1933 as the Depression bottomed out. Interestingly, the Depression probably supplied the impetus for Baptists in the state to hitch their wagon more closely to the Southern Baptist Convention, whose agencies bailed out churches and agencies in Arkansas. But in an overwhelmingly rural state, churches struggled to employ adequately trained pastors and to fund programs.

Prosperous Times, 1950–1978

The state convention’s most prosperous years followed World War II. While the state’s population fell 6.5 percent between 1950 and 1960, membership in Baptist churches connected with the convention rose twenty-nine percent to 304,262. As the general population increased an estimated 1.8 percent per year after 1960, membership in state convention churches went up about 2.15 percent a year between 1960 and 1978, the 130th anniversary of the convention, to 422,146. By comparison, the American (General) Baptist Association manifested little growth from the time of its inception. Indeed, it claimed more churches and members in 1905 than it did in 1971. Whereas in the 1926 census, the American Baptist Association reported 560 churches and 41,281 members, it claimed only 370 churches and 48,716 members in 1971. As the black population dropped from 426,639 to 352,495 between 1950 and 1970, one must assume a significant decrease in the number of Baptists. Methodists, who competed with Baptists up to World War II, also yielded the banner to Southern Baptists as they focused on restoration of unity among Methodists and let evangelistic efforts decline.

The most dramatic change in Baptist church life from 1950 to 1978 related to urbanization. As Arkansas’s population shifted rapidly from farm to city, the number of part-time churches (those not meeting every Sunday and/or unable to hire full-time ministers) dwindled to virtually nothing by 1967. Finances improved markedly, enabling churches, associations, and the state convention to refurbish and build buildings. Urbanization also liberalized attitudes toward other denominations, a practice that clashed with strong Landmark tendencies and led to controversy. In 1965, district associations and the state convention excluded four churches for practicing “open communion”—that is, permitting non-Baptists to share communion—but later readmitted them. Arkansas Baptists played a somewhat conciliatory role in the Little Rock desegregation crisis in 1957 as several ministers signed a petition protesting Governor Orval Faubus’s effort to prevent integration of Central High. Eight-term Congressman Brooks Hays, president of the Southern Baptist Convention, led the effort at the request of President Dwight Eisenhower. The Arkansas Baptist news magazine, under the editorship of Erwin L. Mcdonald, also editorialized for the acceptance of integration. Only one ABSC pastor signed a statement commending Faubus, although several pastors affiliated with the Missionary Baptist Association did so. For some time before this, Baptists affiliated with the state convention had tried to foster ties with two African-American National Baptist groups in the state. The U.S. Supreme Court decision to strike down “separate but equal” education in 1954 prompted them to employ a full-time secretary of race relations. In 1970, this office shifted from “race relations” to “work with National Baptists,” opening the way to cooperative efforts.

Baptists since 1978

The number of Baptists in Arkansas continued steadily upward, with a state population growing about two percent a year from 1978 onward, to an estimated 2,725,714 in 2003. Although the Southern Baptist Convention was embroiled in controversy over interpretation of scriptures for most of this period, churches affiliated with it reported 526,734 members in 1,391 churches in 2004, a growth rate about equal to the population’s. The American Baptist Association remained level, but two National Baptist groups increased as the black population rose again to the 1950 level (around 428,000 in 2003). Other Baptist groups were smaller. Baptists constituted about half of the state’s Christian populace in 2005. Several churches in Arkansas have affiliated with the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, an organization formed in 1991 to counter the conservative movement in the Southern Baptist Convention. A number of prominent Baptist churches and leaders in the state opposed the fundamentalist movement.

Baptists have taken an active part in a number of social issues which crop up repeatedly. From 1900 on, they rallied to the Prohibition movement, and some try to keep counties dry today. The anti-evolution controversy attracted support of conservative Baptists in the 1920s and has resurfaced among them in the effort to place teaching of intelligent design alongside evolution in the public schools. They vigorously aided the war effort in both World War I and World War II by selling bonds, and they entered into the debate precipitated by the wars in Vietnam and Iraq. They wrestled with the Charismatic movement in the 1960s and 1970s, and they have debated and continue to debate the role of women in the churches and in society.

For additional information:

Annual of the Arkansas Baptist State Convention. Little Rock: Arkansas Baptist State Convention. (Earlier titled Proceedings of the Arkansas Baptist State Convention.)

Clark, John Franklin. A Brief History of Negro Baptists in Arkansas: A Story of Their Progress and Development, 1867–1939. Pine Bluff, AR: 1940.

Hinson, E. Glenn. A History of Baptists in Arkansas, 1818–1978. Little Rock: Arkansas Baptist State Convention, 1979.

History of the Ten Years’ Work of the Phillips, Lee and Monroe County District Baptist Association. Helena, AR: Helena World Job Print, 1890.

McBeth, Leon. The Baptist Heritage. Nashville, TN: Broadman Press, 1987.

McLeod, W. E. “Early Baptist Movements in Northeast Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 5 (Summer 1946): 154–168.

Newman, Mark. “The Arkansas State Baptist Convention and Desegregation, 1954–1968.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 56 (Autumn 1997): 294–313.

Rogers, J. S. History of Arkansas Baptists. Little Rock: Arkansas Baptist State Convention, 1948.

Taylor, Orville W. “Baptists and Slavery in Arkansas: Relationships and Attitudes.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 38 (Autumn 1979): 199–227.

Williams, C. Fred, S. Ray Granade, and Kenneth M. Startup. A System & Plan: Arkansas State Baptist Convention, 1848–1998. Franklin, TN: Providence House Publishers, 1998.

E. Glenn Hinson

Baptist Theological Seminary at Richmond

Antioch Baptist Church

Antioch Baptist Church  Arkansas Baptist College

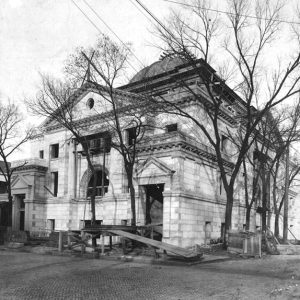

Arkansas Baptist College  Arkansas Baptist State Convention HQ

Arkansas Baptist State Convention HQ  Joseph A. Booker

Joseph A. Booker  Camden Baptist Church

Camden Baptist Church  Crigler Church

Crigler Church  De Ann Baptism

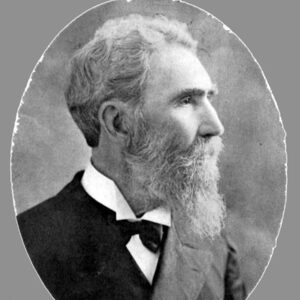

De Ann Baptism  James Eagle

James Eagle  First Baptist Church

First Baptist Church  Glenwood Baptism

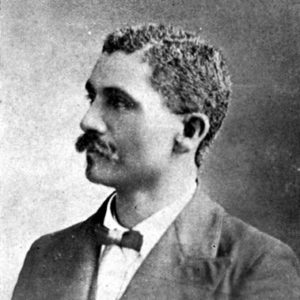

Glenwood Baptism  Elias Morris

Elias Morris  Ouachita Baptist College Chapel

Ouachita Baptist College Chapel  Ouachita Baptist University

Ouachita Baptist University  Second Baptist Church

Second Baptist Church  Star City Baptism

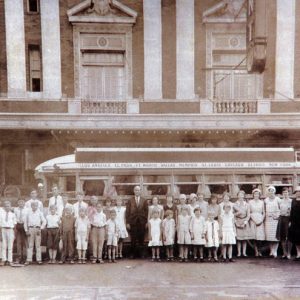

Star City Baptism  Texarkana Baptist Orphanage

Texarkana Baptist Orphanage  Texarkana Baptist Orphanage

Texarkana Baptist Orphanage  Silas Toncray

Silas Toncray

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.