calsfoundation@cals.org

Benton (Saline County)

County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 34º33’52″N 092º35’12″W |

| Elevation: | 416 feet |

| Area: | 22.88 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 35,014 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation date: | March 15, 1836 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

452 |

647 |

1,025 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

1,708 |

2,933 |

3,445 |

3,502 |

6,277 |

10,399 |

16,499 |

17,717 |

18,177 |

21,906 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

30,681 |

35,014 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Benton is on the Southwest Trail, an old Indian trail that was part of the National Road leading from Missouri through Jackson and Lawrence counties to Little Rock (Pulaski County), then south to the Red River. Benton is accessible by Interstate 30, the Union Pacific Railroad, and the state’s commercial airport. Thirteen properties, including a mound site and a bridge, are on the National Register of Historic Places. Though the aluminum industry was located in nearby Bauxite, Benton served as an employee, a service sector, and a medical and entertainment base for Reynolds Metals and Alcoa Inc.

Pre-European Exploration

It is thought that Hernando de Soto and his band traveled down the North Fork of the Saline River in 1541 and visited the site where Benton stands. They found the country densely populated with Native Americans. It would be nearly 300 years before another white man would come that way. A de Soto trail marker rests at the old junction of U.S. Highways 67 and 70. It is a large boulder of bauxite ore on a gray granite base with a cast aluminum tablet bearing the inscription, “De Soto Trail. By here the De Soto expedition marched September 7, 1541. Erected 1935 by citizens of Saline County.”

The area has two significant Indian mounds. The John L. Hughes Indian mound, three miles southwest and 100 yards from the Saline River, is 80 feet high and 110 feet long. Another mound equally as large is on the Albert Thomas farm across North Fork five miles northwest of Benton.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

Named after U.S. Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri Territory, the town began in 1833 on the east bank of the Saline two years before the county was established. Rezin Davis deeded eighty acres to Benton and became its first mayor. The first business, opened in 1834, was an in-house store owned by Joshua Smith. The next year, this “neighborhood” became Saline Township, and Green B. Hughes was appointed postmaster. He owned one of several area gristmills.

After Arkansas became a state in 1836, local commissioners from the newly formed townships were elected to set a permanent county seat. There were three choices. Benton, which was situated on the road from Little Rock, had the advantage of being more populous, nearer the center of the county, and more prestigious because of the long existence of Saline Crossing. Ezra M. Owen campaigned for Collegeville, which was also on the main road but lay several miles east. Charles A. Caldwell, representative for Saline County, wanted the county seat to be in Caldwellton, where he had settled. It was five miles northwest of the present town of Benton near the Kentucky community. He procured enactment of a law providing for a November 7, 1836, election at which voters would choose five commissioners to select the official site. Elected were Rezin Davis, Jesse Bland, David Dodd, Jarrett McCarty, and Abijah Davis; they chose Benton.

The first courthouse and jail were built in 1838. That year, a Jockey Club and horse track were constructed, and Mrs. Jeffries’s Female School was organized. Ten years later, Benton was considered a small village.

The only documented lynching recorded in Saline County occurred in 1854, when a slave known only as “Toll” was hanged near the second Saline County Courthouse in Benton.

Civil War through Reconstruction

On September 10, 1863, six weeks after the Union army under General Frederick Steele captured Little Rock, Union soldiers moved south, building Fort Bussey in north Benton and earthworks in the western part of the city. Four regiments occupied the city until Christmas, commandeering the James Henry Shoppach and the William Ayers Crawford houses for headquarters. Confederates won a victory with the Skirmish at Benton in December 1863, but the following summer saw two Union victories with an Affair at Benton in July and another Skirmish at Benton in August.

Six Confederate regiments raised in Benton that had prominent Benton men as officers and leaders were the Eleventh Arkansas Infantry; Company E, First Arkansas Infantry; Company C, Third Arkansas Cavalry; Company D, Hawthorn’s Arkansas Infantry; Company B, Crawford’s Cavalry; and Company B, Twenty-Fifth Arkansas Infantry. Important Benton officers were James Fagan, William A. Crawford, Mazarine Jerome Henderson, George M. Holt, and Jabez Smith. Boy martyr David O. Dodd lived in Benton at the outbreak of the war, and his mother and sisters lived there until 1863.

Because Benton was so close to the fighting in Little Rock, it was not occupied during Reconstruction. During the Brooks-Baxter War, Colonel James F. Fagan was made a militia general and commanded Joseph Brooks’s forces in Little Rock, while the aforementioned Colonel Crawford found himself on the other side as brigadier general of militia for Elisha Baxter’s forces.

Post Reconstruction through Modern Era

In 1881, Benton’s population was 400. In 1882, the Ashby Funeral Home was established; members of the original family still operate it. In 1894, two African-American families, the Rhineharts and the Canadys, bought property south of the city on the west end of Palm Street. Some of that land later had to be sold to the railroad company. What is now Benton Utilities was established in 1916 with the creation of the Benton Municipal Waterworks. In the 1930s and 1940s, black workers in the bauxite mines lived in Bauxite at the Mexico Camp. The Republican Mining Company was sold to Alcoa, which wanted to mine the camp area. The workers migrated to Alexander and to Benton’s Gravel Hill community—now known as Southside or Hardscramble—and developed settlements.

Because of the Great Depression, the town’s only bank closed, thousands were without work, many people left, and family farms sold for twenty-five cents on the dollar. W. R. Alsobrook opened Benton State Bank (now Regions) in 1934. The bank still stands on its original site.

At least 137 Benton-born men and women served in World War II. The most famous was Ewell Ross McCright, who, while a prisoner of war, made notes on cigarette papers that he kept on his body. The information filled four ledgers and was later used in the Nazi trials at Nuremberg. The War Department used these ledgers to clarify and complete some of its own records.

After World War II, the aluminum plants turned to peacetime production, making sheet plate and foil. The last bauxite ore extracted from the Reynolds Hurricane Creek Plant was at the E-40 mine in February 1983. The Reynolds plant site now houses the Saline County Career Center. Benton is one of the outlying areas that are bedroom communities feeding commuters into Little Rock. Proximity to lakes in Hot Springs (Garland County) and Arkadelphia (Clark County), to the Winona Wildlife Management Area, to the Ouachita National Forest—all for recreation—and to Little Rock for cultural and sports events, as well as the reputation of area schools, has drawn people to the town.

The August 17, 1969, killing of an African-American man, Leonard Lee Williams, at a local restaurant sparked extensive protest by the black community in Benton. The mayor responded quickly with the establishment of a committee on race relations, but no one was ever convicted of the killing.

A devastating flood in 1978 caused millions of dollars in damage and killed three in Benton.

Saline Memorial Hospital was constructed in 1954 in response to the rising population of the Benton area following World War II, the Korean War, and Saline County’s postwar industrial boom. When it opened, it had forty-two beds; now, it has more than 175.

Education

In 1838, the advertisement for Mrs. Jeffries’s Female School called Benton “a flourishing village in a high and healthy country … with the best of water.” Spelling, reading, writing, arithmetic, English grammar, and geography—with globes—was offered for $12.50 for a five-month term. If other subjects were desired, the price was $15. Pupils boarded with the “best” families. It is presumed the Jeffries school lasted until 1843, when the Benton Academy was incorporated.

In 1883, the Shady Grove School on North Market Street contained two sections. The front held the advanced students, and the primary pupils were assigned to the back. Desks were straight and uncomfortable and used only for writing. Otherwise, the students stood.

In 1885, the building that eventually became the home of Henry Jackson Gingles housed the Baird Institute, a private school lasting only a few years. That year, two classes moved to South Market and soon expanded to five rooms with double desks. Two principals and five teachers taught eight grades. From 1896 to 1899, the high school curriculum included algebra, Greek, and rhetoric. The first graduating class in 1899 had four girls and four boys. Professor A. E. Wilson introduced the graded system and added a sixth teacher.

There was no school in 1904–05 because of a lack of funds. During that time, the teachers taught in private schools. In 1906, a grammar school building was built and the first football team fielded. In the black community, schools were held in churches but eventually moved to the Odd Fellows Hall. In 1910, the government-funded Gravel Hill School was built to serve black children.

In 1913, the high school building was erected. A decade later, the system included sixteen teachers and rose from “C” classification to “A” to earn North Central Association accreditation. In 1926, Gravel Hill was closed because of the sale of land it was on. As late as 1933, school buses were used only for group trips. In 1935, a new high school building was built. Attendance was more than 1,200, with twenty-six faculty. In 1947, the Ralph Bunche School was established for black children; by 1958, it served 147 students. By 1968, the school, with seventy-six students, merged into the Benton School District.

By 2005, 4,257 students were housed in seven buildings: senior high, junior high, middle school, and four elementary schools—each in a different part of the city. A branch of the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (UALR) operated in Benton from 1994 until 2020, when it closed. In August 2021, the Saline County Career Technical Campus opened in Benton. A partnership between six public school school districts and Arkansas State University Three Rivers, the site offers a variety of workforce training options.

Industry

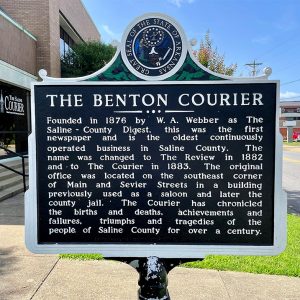

The Saline Courier (formerly known as the Benton Courier) was established in 1876. It is the largest and oldest newspaper in Saline County. An opposing paper, the Saline County News (later the Saline County News-Pacesetter), existed between 1955 and the mid-1950s.

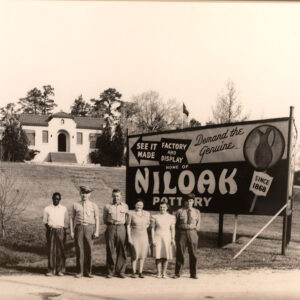

Benton’s primary industry at the turn of the twentieth century was pottery. There were thirteen firms, the most famous of which belonged to Charles Hyten. Niloak Pottery, named from the reverse spelling of kaolin, a richly colored clay found in the area, produced utilitarian jugs, churns, crocks, and flowerpots, known as Eagle pottery, and the one-of-a-kind swirled art pottery called Niloak, which is collected the world over. In 1934, Hyten lost the business, and the new management from Little Rock began making molded, glazed pieces called Hywood. The Hyten House is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In the 1930s, construction of the State Hospital for Nervous Diseases (now the Arkansas Health Center) provided significant employment in construction and in the service and medical sectors. Sawmills, building materials, lumber, and furniture manufacturing used the surrounding timber resources. Today, steel fabrication, ceramics, asphalt, veneer, gravel, concrete, and marine parts are important in the city’s industry.

Hurricane Lake, a 332-acre manmade lake, has been privately owned by several companies.

Attractions

The Shoppach House, ca. 1850s, was the first brick house built in Benton. It is on the National Register of Historic Places. It stands where it was built and can be seen from the junction of Military Road and Carpenter Street. The Bennett House on First Street was constructed in 1904 in the Folk Victorian style and is also listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Royal Theatre, built in the early twentieth century, was originally known as the IMP (Independent Motion Pictures) and was owned by Alice Wooten. Wallace Kauffman bought the theater in 1922. Today, it houses productions of the Royal Players and the Young Players, a Benton-based theater group. The theater, on the National Register, received a grant from the Arkansas Historic Preservation Program in 2005. The theatre is located within the bounds of the Benton Commercial Historic District.

The Gann Building, now housing the Gann Museum, was built in 1893 as an office by patients of Dr. Dewell Gann Sr. who could not pay cash for services. It was constructed of bauxite that was mined from a nearby farm and hand-sawed into blocks and allowed to harden. A Victorian building with three rooms, it contained two entrances to two waiting rooms, one for women and one for men, and the examination room. Dr. Dewell Gann Jr. gave it to Benton in 1946 for use as a county library. The building became a museum in 1980 and houses artifacts from early Benton and Saline County. In 1975, it and the Gann House were added to the National Register of Historic Places.

The Dr. James Wyatt Walton House, the Dr. T. E. Buffington House, the Palace Theatre, the James Phillip Smith House, and the International Harvester Servicenter are all listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Located outside of town northeast of Benton is the Rowland-Lenz House, also listed. Benton is also home to one of nineteen examples of post office art in the state, dating back to the Depression era. The Hughes Cemetery is listed on the Arkansas Register of Historic Places.

A competitive spirit between Benton and Bryant high school football teams led to the creation of the Salt Bowl, held every fall since 2000. The game attracts fans and alumni from all over Saline County and averages attendance of over 20,000.

Notable Figures

Benton has served as host to several Hollywood figures. The 1973 movie White Lightning, starring Burt Reynolds, was filmed in Benton. In 1996, Billy Bob Thornton filmed parts of Sling Blade at the former State Hospital and on the Old River Bridge. Stuart Greer, an actor, was raised in Benton.

George Washington Lucas was a young Union soldier who was awarded a Medal of Honor for killing an Arkansas militia general in Benton during the Civil War. Charles Franklin Cunningham Sr. was the first African American to serve as mayor of Benton. Steve Landers is a businessman from Benton who founded Arkansas’s largest chain of automotive dealerships. Doyle L. Webb II is a lawyer and a former state senator.

Bruce “Sunpie” Barnes, born in Benton, went on to work with the Natural Park Service, play in the National Football League (NFL), and become a musician. Professional basketball player Glen Anthony Rice spent his childhood in Benton. Japanese-American Ryan Kurosaki played major and minor league baseball before retiring to Benton. Jack “Spadjo” Richards was an amateur boxer, former Razorback, and professional football player. Major league baseball player Cliff Lee was born in Benton.

Norman Eugene Smith was a classically trained pianist. Adam Faucett is a singer, songwriter, and guitarist.

For additional information:

“Benton’s Historic Royal Theater Receives Grant.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Tri-Lakes Edition. July 21, 2005, pp. 1T, 6T.

Hollenbeck, Lynda. “New Face, New Place.” Benton Courier. August 15, 2005, pp. 1, 5.

Newman, Marvin, ed. Recollections of Saline County. Marceline, MO: D-Books Publishing Inc., 1997.

Wright, Arnold A. My Country Called. Benton, AR: Benton Printing and Composition, 1993.

Patricia Paulus Laster

Benton, Arkansas

Alcoa Aluminum

Alcoa Aluminum  Anderson's Esso

Anderson's Esso  Bauxite and Northern Railroad

Bauxite and Northern Railroad  Bennett House

Bennett House  Benton Bridge

Benton Bridge  Benton Airplane

Benton Airplane  Benton Center

Benton Center  Benton City Jail

Benton City Jail  Benton High School

Benton High School  Benton Street Scene

Benton Street Scene  Benton Street Scene

Benton Street Scene  Benton Street Scene

Benton Street Scene  Benton Waterworks

Benton Waterworks  Courier Commemorative Plaque

Courier Commemorative Plaque  Charles F. Cunningham

Charles F. Cunningham  Gann House

Gann House  Gann Museum

Gann Museum  Gann Row Houses

Gann Row Houses  Hurricane Creek

Hurricane Creek  Joe’s Cafe

Joe’s Cafe  Newcomb Township Centennial Float

Newcomb Township Centennial Float  Niloak Customers

Niloak Customers  Niloak Factory

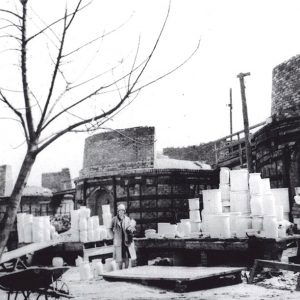

Niloak Factory  Niloak Kilns

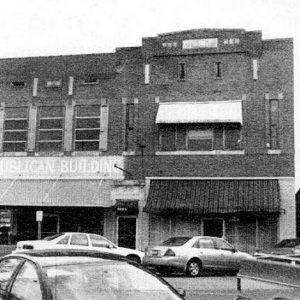

Niloak Kilns  Odd Fellows Building

Odd Fellows Building  Owosso Manufacturing Co.

Owosso Manufacturing Co.  Republic Centennial Float

Republic Centennial Float  Royal Theatre Marquee

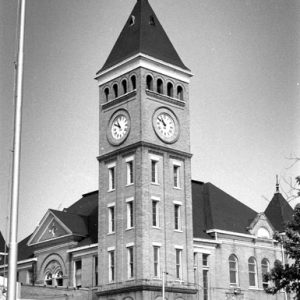

Royal Theatre Marquee  Saline County Courthouse

Saline County Courthouse  Saline County Courthouse Lawn

Saline County Courthouse Lawn  Saline County History and Heritage Society

Saline County History and Heritage Society  Saline County Map

Saline County Map  Saline Memorial Hospital Sign

Saline Memorial Hospital Sign  Saline Memorial Hospital

Saline Memorial Hospital  White Lightning Car

White Lightning Car

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.