calsfoundation@cals.org

Crittenden County

| Region: | Northeast |

| County Seat: | Marion |

| Established: | October 22, 1825 |

| Parent County: | Phillips |

| Population: | 48,163 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 612.86 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical Population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

1,272 |

1,561 |

2,648 |

4,920 |

3,831 |

9,415 |

13,940 |

14,529 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

22,447 |

29,309 |

39,717 |

42,473 |

47,184 |

47,564 |

48,106 |

49,499 |

49,939 |

50,866 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

50,902 |

48,163 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

19,276 |

40.0% |

| African American |

25,905 |

53.8% |

| American Indian |

136 |

0.3% |

| Asian |

327 |

0.7% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

17 |

0.0% |

| Some Other Race |

683 |

1.4% |

| Two or More Races |

1,819 |

3.8% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

1,428 |

3.0% |

| Population Density |

78.6 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$40,161 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$23,172 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

22.2% |

|

Crittenden County is located in east-central Arkansas. Its eastern and southern boundaries are the Mississippi River. To its west are Lee, St. Francis, and Cross counties. Mississippi County and Poinsett County form its northern borders. According to historian Margaret Woolfolk, “Crittenden is entirely on the bottom land of the Mississippi River….Total thickness of the sediment exceeds 100 feet.” Because of its astonishing fertility, the area became an obvious location for agricultural development. In the modern era, it has also become a major transportation thoroughfare.

European Exploration and Settlement

Artifacts found in Crittenden County—including effigy pipes, stone ear plugs, and ornaments—testify to a long habitation of the area by Native Americans. Some archaeologists place the location of Pacaha, visited by the expedition of Hernando de Soto, within the present borders of the county. Crittenden County was later settled by Spanish grantees. Its first resident of note was a Spanish sergeant named Augustine Grande, who was the commander of Fort Esperanza, built by the Spanish in 1795 on the west bank of the Mississippi River. Title to the land was passed to France in 1801. When the title passed to the United States in 1803, Grande decided to remain in the area, where he held power of attorney for numerous Spanish grantees and was said to be active in numerous land transactions. His will, probated in 1828, gave to his wife the “negroes, herds, horses and cattle.”

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

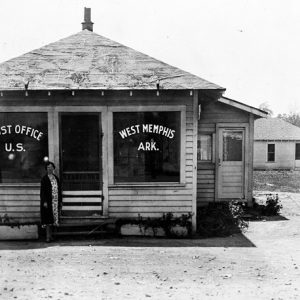

Named for Robert Crittenden, the first secretary of the Arkansas Territory, Crittenden County, the twelfth to be created, came into being on October 22, 1825. The first county seat was Greenock, but the community failed after it was bypassed by a military road connecting Memphis to Arkansas. The only physical remnant of the settlement is a cemetery. Marion was then selected as the county seat and inaugurated the first session of the county court on April 12, 1836. West Memphis, Crittenden County’s largest city, was formerly called Garvey. Located on the west bank of the Mississippi River south of the community of Hopefield, West Memphis was named by General George Nettleton, an official of the Kansas City and Fort Scott Railroad; however, it was not until 1893 that postal authorities recognized the name. Smaller communities formed early in the county’s history include Crawfordsville, Horseshoe Lake, Gilmore, Jericho, Edmondson, Jennette, Sunset, Clarkedale, and Turrell.

The steamship Brandywine burned and ran aground near Turrell in 1832.

Two unnamed enslaved men were hanged in the county in 1840 for the alleged killing of their master. This event would be the first in a number of incidents of racially related violence in Crittenden County.

Civil War through Reconstruction

Represented by wealthy planter Thomas H. Bradley at the Secession Convention, Crittenden County was heavily dependent on slave labor in 1860. The white population that year was recorded as 2,573, with a total of 2,347 enslaved persons in the county. Bradley owned ninety-five enslaved people at the time of the census, making him the largest slave holder at the convention.

Though no major battles were fought in Crittenden County, government activities virtually ceased during the Civil War. The towns of Hopefield and Mound City were burned by Federal forces to prevent the use of the buildings by Confederate troops and guerrillas.

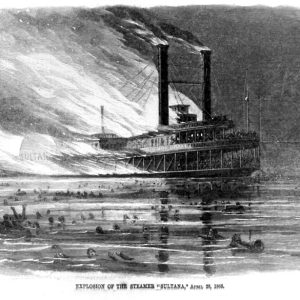

The Sultana, a steamboat tasked with transporting freed Union prisoners of war home from southern prison camps, exploded and burned on April 27, 1865, claiming up to 1,800 lives. The wreckage is now located under a field in Crittenden County.

With a county electorate after the war that was now sixty-seven percent African American—because many supporters of the Confederacy had been declared ineligible to vote in 1867 as a result of the Reconstruction Acts—racial difficulties within the county during this time period became the rule rather than the exception. As a terrorist organization that refused to accept the new Republican order, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) was extremely active in Crittenden County. Throughout parts of Arkansas, the Klan intimidated, threatened, and murdered African Americans, as well as whites who supported the Republican Party. The response of the Republican governor, Powell Clayton, was to declare martial law in fourteen counties, including Crittenden County. To implement his decision, Clayton prevailed upon the legislature to create a state militia that included African Americans. A number of fierce skirmishes ensued. Only the intervention of William Monks, who commanded 600 troops from Missouri, saved a detachment of black militiamen from being slaughtered at the county courthouse in Marion. In the late 1860s, hundreds of black citizens in Crittenden County periodically sought protection from plantation owner E. M. Main, who was a Freedmen’s Bureau official succeeding his murdered predecessor.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

By 1874, Reconstruction in Arkansas had ended, and the Democrats returned to power. With its heavily black populations now empowered with the right to vote for adult males (due to the Fifteenth Amendment), the eastern part of the state presented a major problem for powerful whites trying to keep black workers satisfied enough to stay in Arkansas and provide the essential labor force that kept the plantation system going. The political solution in most of these counties, including Crittenden, was known as “fusion.” Each election cycle, white and black residents agreed in advance upon a division of county offices and representation in the legislature. Though whites invariably retained most of the important offices (even as of 2008 there has been only one black county judge in the state), fusion worked after a while. Indeed, by 1888, African Americans occupied the following major offices in Crittenden County: judge, county clerk, assessor, and a representative in the state legislature. Woolfolk writes that “a group of about 80 whites assembled at Marion about 10 a.m. July 13, 1888, and marched to the courthouse where David Ferguson [the county clerk] was forced to resign at the muzzle of a Winchester rifle….Other blacks were taken by wagon to the Mississippi River, then by boat to Memphis, and released.” Despite the fact that Crittenden County was overwhelmingly black in 1888, no African Americans were afterward elected to a county office for the next 100 years.

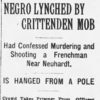

Several incidents of violence took place in the county in the late nineteenth century, including the lynching of African American Isaac Ruffin for allegedly killing an African American girl and raping her sister. In 1888, an African-American man named Jim Smith was lynched in Crittenden County for allegedly propositioning a white woman.

Because of the county’s location, levees and drainage districts have been essential to its development. An act of Congress in 1850 created the first organized efforts toward levee construction as well as the donation of approximately 8,600,000 acres of swampland to Arkansas to be sold to make levee and drainage systems possible. By 1852, a three-foot levee had been developed along the Mississippi River for most of the county’s border. It was not until 1893, however, that major flood control efforts resulted in the Arkansas legislature’s creation of the St. Francis Levee District. Bonds were issued, and a levee had been constructed almost from the Missouri state line into Crittenden County in 1897 when spring floods turned the county into a “perfect Venice.”

The third-largest city in Crittenden County is Earle in the western part of the county in Tyronza Township, a mile east of the Crittenden–Cross County line. Named for Confederate officer Josiah Francis Earle and later active Ku Klux Klan leader, Earle received its first postmaster in 1890 and prospered in the early days of the county because of the lumber industry. At one time, it was the largest city in Crittenden County.

George Corvett was lynched on February 12, 1890, two miles west of Crawfordsville.

Early Twentieth Century

Multiple incidences of violence, with some racially motivated, were perpetrated in the county in the early part of the twentieth century. Nat Mullens was lynched for allegedly killing a deputy sheriff in 1900. Robert Austin and Charles Richardson, both Black men, were lynched by a white mob on March 18, 1910, for allegedly assisting in a jail break. Hanged for the alleged killing of John Millett, a white man, African American Warren Fox was lynched on July 9, 1915. Elton Mitchell was lynched for the alleged shooting of a white woman on June 13, 1918. Additional lynchings took place in the county in 1890, 1903, and 1917.

Though there have been no Mississippi River levee breaks since 1927, the floods of 1927 and 1937 rendered hundreds of families in Crittenden County homeless because of backwaters from the St. Francis River. Because natural drains were blocked by the levee, Crittenden County landowners have been forced to rely on the creation of drainage districts. Since 1899, bonds have been issued to raise money for drainage districts throughout the county. Completion of the ditches eliminating swamps and brakes have allowed thousands of acres to be used for agricultural purposes.

Between 1900 and 1936, six black men were lynched in the county. It may well have been more. With the Great Depression, Crittenden County exhibited some of the worst abuses perpetrated in the name of white supremacy. In 1936, a gang of white riding bosses and planters entered the Providence Methodist Church outside of Earle where 450 black sharecroppers were gathered for a meeting of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union and began beating them with ax handles and pistol butts. That same year, Paul D. Peacher, a deputy sheriff of Crittenden County who had his own farming operation on the side, was revealed to be engaging in peonage. “Slavery in Arkansas” ran a headline in Time magazine on December 7, 1936.

Historian Michael Dougan has written that the town of Crawfordsville spent fifty-seven dollars on white education for every dollar spent on education for African Americans. According to Woolfolk, Marion, the county seat, “never had a school building for the sole purpose of Negroes’ education.” It was not until 1925 that an elementary school for black children was built outside of Marion in the all-black community of Sunset. Though some high school courses were available after 1935, people wanting higher education were forced to go to schools in Memphis, Little Rock, St. Louis, and elsewhere. Even the high school courses that were available at Phelix High School in Sunset were not free to black students. Though buses were provided for white students, buses for black students were not used until the fall of 1946.

In addition to facilities for railroads, the first industry to be located in West Memphis was Bragg Mill, which in the 1920s used 200 mules and 200 oxen. Taylor Bragg owned 3,000 acres of land. The Federal Compress & Warehouse Company opened in 1923 and at one time had a capacity of 165,000 bales, making it the state’s largest compress. It was demolished in 1980.

An early movie with sound was partially shot in the county. Hallelujah, filmed in 1929, was not only one of the first films with an entirely African American cast, but was also notable as an early film with sound recorded on location rather than in a studio.

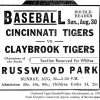

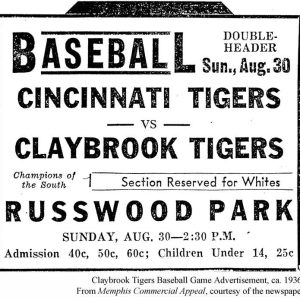

The Claybrook Tigers, a professional baseball team of African American players, competed against other professional teams in the Negro Leagues in the 1930s.

World War II through the Faubus Era

The state of black education continued to draw national attention to Crittenden County. In the March 21, 1949, issue of Life magazine, an article with accompanying photographs dealt with the conditions of black education in West Memphis, which spent an average of $144.51 for each white child’s education and $19.51 for the education of each black child. Photographs revealed the crowded conditions in the black school, which had been partially destroyed by fire. Some 310 students and their five teachers were squeezed into five rooms of the gutted building, and 370 more were packed into a one-room church. On September 27, 1949, a bond issue for a new black school was defeated. Meanwhile, a new $300,000 facility for 900 white children had just opened. Not until 1971 did the first black students graduate from Marion High School.

Racially based violence continued to plague the county during this period. Isadore Banks, a wealthy African American landowner, was murdered in 1954 and the case remains unsolved. Andrew Lee Anderson was killed by a group of citizens and deputy sheriffs after being accused of sexually assaulting an eight-year-old white girl. A march to protest the continued segregation of public schools in Earle led to the shooting of several African Americans in 1970. Ezra Greer, an African American pastor and organizer of the event, and his wife Jackie Greer were among those shot and wounded.

Modern Era

Because it was not as affected as the rest of the county during the Depression, West Memphis continued to grow from a population of 895 in 1930 to 3,369 in 1940. It more than doubled in size during the war years and, by 1950, had a population of 9,112. By 1990, it had a population of 28,259; in that year, an estimated 2,000 people were employed in a variety of jobs by West Memphis processing and manufacturing industries, turning out products such as truck tires, Christmas ornaments, laminated materials, water treatment chemicals, and welding fittings. According to Woolfolk, West Memphis’s growth could be attributed to the city’s location, its development as the county’s financial center, and its industrial and business developments. Though population growth has been stagnant in recent years, due in part to “white flight,” the city’s prime location at the crossroads of Interstates 40 and 55 and major rail routes has enabled it to maintain its economic base as a major transportation center. Though agriculture is still a crucial aspect of the economy, King Cotton has been dethroned by the soybean, and with the enormous costs inherent in food production, there is no room for the small farmer. The average size of farms in the county is 1,284 acres.

Post-secondary educational opportunities for citizens of Crittenden County became available with the opening of Mid-South Vocational Technical School in 1982. The institution grew and evolved into the present-day Arkansas State University Mid-South.

National media descended on the county in 1993 when three boys were discovered murdered in West Memphis. The ensuing trial and conviction of three teenagers (who became known as the West Memphis Three) and subsequent documentaries and books continued to keep the case in the public spotlight The three were eventually released from prison after accepting an Alford Plea in 2011 but continued their efforts to have their names cleared.

With the shooting fatality of twelve-year-old De Aunta Farrow by a West Memphis police officer in 2007, racial tensions have continued, in some ways, to define West Memphis, the largest city in the county. Like other towns in the Arkansas Delta, West Memphis experiences political battles divided along racial lines. At the same time, Marion, the county seat, has experienced dramatic growth in the twenty-first century as it became known as a bedroom community for Memphis and has attracted white West Memphis residents to its school system.

Attractions in the county include Wapanocca National Wildlife Refuge, centered on a 600-acre lake, and the Sultana Disaster Museum in Marion. Southland Park Gaming and Racing is located near the intersection of Interstates 40 and 55.

For additional information:

Claiborne, Taylor, ed. West Memphis, 1927–1976. West Memphis, AR: Printing Crafts Inc., 1976.

The Crittenden County Rambler: Guide to Historic Places. West Memphis, AR: Crittenden County Historical Society, 1983.

Jones, Krista Michelle. “‘It was awful, but it was politics’: Crittenden County and the Demise of African American Political Participation.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2012. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/466/ (accessed July 6, 2022).

Woolfolk, Margaret Elizabeth. A History of Crittenden County, Arkansas. Greenville, SC: Southern Historical Press, 1993.

Grif Stockley

Little Rock, Arkansas

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Henderson State University

Anthonyville (Crittenden County)

Anthonyville (Crittenden County) Arkansas State University Mid-South

Arkansas State University Mid-South Banks, Isadore (Murder of)

Banks, Isadore (Murder of) Bauxippi (Crittenden County)

Bauxippi (Crittenden County) Clarkedale (Crittenden County)

Clarkedale (Crittenden County) Claybrook Tigers Baseball Team

Claybrook Tigers Baseball Team Edmondson (Crittenden County)

Edmondson (Crittenden County) Fox, Warren (Lynching of)

Fox, Warren (Lynching of) Greenock (Crittenden County)

Greenock (Crittenden County) Hopefield, Burning of

Hopefield, Burning of Sultana

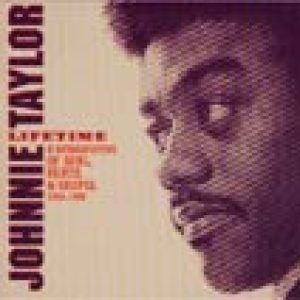

Sultana Taylor, Johnnie Harrison

Taylor, Johnnie Harrison Wapanocca National Wildlife Refuge

Wapanocca National Wildlife Refuge West Memphis Three

West Memphis Three Claybrook Tigers Ad

Claybrook Tigers Ad  The Coffee Cup

The Coffee Cup  Crittenden County Courthouse

Crittenden County Courthouse  Crittenden County Map

Crittenden County Map  Crittenden County Museum

Crittenden County Museum  Earle Street Scene

Earle Street Scene  Asa Hodges

Asa Hodges  Horseshoe Lake

Horseshoe Lake  "I Believe in You (You Believe in Me)," Performed by Johnnie Taylor

"I Believe in You (You Believe in Me)," Performed by Johnnie Taylor  Sultana Disaster

Sultana Disaster  Swepston Mercantile Building

Swepston Mercantile Building  West Memphis Post Office

West Memphis Post Office  West Memphis

West Memphis  West Memphis Flood

West Memphis Flood

I was born and raised in Crittenden County (Crawfordsville area) and never before have I ever heard of or read about many of these atrocities that occurred there and in the surrounding cities. Only bits and small pieces of some of these historical stories I can faintly recall. However, I do recall one of my first encounters with racism as a small child while at a store in Marion, Ark. I never will forget it–the first time I was called the “n-word” to my face by a little white girl who couldn’t have been much older than myself.

Even in today’s time Crittenden County still suffers from racism, KKK members, and the lack of black political leaders, lawyers, and judges. Case in point, some town council creates and passes new town ordinances that affect every property owner in the town to basically say no one can add to or rebuild their home if it does not meet the lot size designated by the council regardless of how long you have owned your property or if you ask for permission (and then have to pay if granted). Exception of those who have larger size lots (mainly those who live across the track since this town has always been divided by the train track- old school segregation) and those who have recently built new homes that so happen to have larger lots than the ordinance call for, the rights to do what they wish. And how convenient the current regime may have used or mis-used its power to enforce some unheard of property bylaws / town ordinances which many of the town residents had no knowledge of until after the town council voted. Sad to say some games never change; they just have new players in a new era of time.