calsfoundation@cals.org

Architectural Styles

A region’s architecture “speaks volumes about the culture of the inhabitants and their level of technology,” notes the Arkansas Historic Preservation Program. Over time and space, several styles have developed to reflect cultural changes and moods. James Curtis, in the Journal of Cultural Geography, writes that a “distinctive architectural style…is often the most enduring and expressive manifestation of the spirit of an age.”

Architecture fits into two broad categories—traditional (folk) houses and high style houses designed by architects who try to set or follow trends. From early settlers’ simple log structures to the elaborate Victorian styles of the nineteenth century to today’s Modern styles, Arkansas’s architecture reflects the trends of the rest of the country.

From the early to mid-1800s, three popular styles appeared in Arkansas: French Colonial, Federal, and Greek Revival. Estevan Hall (ca. 1826) in Phillips County is an example of French Colonial. Such structures usually have hipped roofs, narrow doors, and windows with shutters. Federal architecture is balanced and symmetrical. The Federal-style Confederate State Capitol (ca. 1836) in Hempstead County and the Absalom Fowler House (ca. 1840) in Little Rock (Pulaski County) have horizontally and vertically aligned windows. Greek Revival architecture is characterized by columns and a low-pitched roof, and the roof’s cornice line usually is accentuated by wide trim. The Frog Level Plantation (ca. 1854) in Columbia County is an example of Greek Revival architecture.

From the mid- to late 1800s, Gothic Revival, Italianate, and Second Empire styles became popular, and Arkansas has examples of each. Gothic Revival structures tend to have steep roof pitches with many of the edges decorated with “gingerbread” and ridge rows adorned with finials. The Edward Dickinson House (ca. 1875) in Independence County is in the Gothic Revival design, as is the Trinity Episcopal Church (1866–1871) in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County). Italianate, or Italian Villa style, buildings often have tall, round-topped windows, are more than one story tall, and usually possess a square tower. Examples include the Bonneville House (ca. 1870) in Fort Smith (Sebastian County) and Little Rock’s Capital Hotel (ca. 1873). Second Empire characteristics include Mansard roofs along with extensive use of brackets, primarily under the eaves. The Villa Marre (ca. 1882) in Little Rock, which also has ironwork on top, is a prime example, as is the Old Jackson County Courthouse (ca. 1869–1872).

Two other architectural styles appeared near the end of the nineteenth century: Queen Anne and Romanesque Revival. Wilcox notes that many Queen Anne structures are irregularly shaped and have asymmetrical façades. Bays, balconies, towers, and turrets are associated with Queen Anne architecture. The Queen Anne Pillow-Thompson House (ca. 1896) in Helena (Phillips County) exhibits most of these qualities. Romanesque Revival architecture is also identified with asymmetrical façades but normally has arches over windows or doors. The James K. Barnes House (ca. 1893) in Fort Smith fits this description, as does the Berger-Graham House (ca. 1904) in Jonesboro (Craighead County).

Many architectural styles developed at the end of the nineteenth century: Colonial Revival, Neoclassical, Prairie, Craftsman, Tudor Revival, Art Moderne, and Art Deco. Colonial Revival residences typically have the front entrance as the focal point on a symmetrical façade, along with multi-paned windows. Examples include the Bishop-Brookes House (ca. 1925) in De Queen (Sevier County) and the Lake Village Post Office (ca. 1938) in Chicot County. Neoclassical architecture is identified by the use of columns and symmetrical façades and is commonly associated with honorific public buildings. Many of Arkansas’s county courthouses (such as those in Lonoke and Phillips counties, for instance) fit this category. Residential Neoclassical examples tend to be large and built for upper-class families. The Galloway House (ca. 1910) in Monroe County is an example. Prairie style emphasizes horizontal construction through low-pitched roofs and wide eaves. Prairie representations include the MacMillan House (ca. 1903) in Pine Bluff and the Naff House (ca. 1919) in Portland (Ashley County). Craftsman homes and buildings exhibit just that, craftsmanship. The Marshall House (ca. 1908) in Little Rock and the Russell House (ca. 1925) in Fordyce (Dallas County) reflect the quality of the Arts and Crafts movement. Houses of Tudor Revival, often referred to as Elizabethan or half-timbered, have steep roofs and typically have prominent chimneys. Half-timbered buildings have exposed framing, and the spaces are filled with brick or stone. Two such houses are the Wood Freeman House (ca. 1934) in Searcy (White County) and the Charles Murphy House (ca. 1925–1926) in El Dorado (Union County).

The machine age and space travel greatly influenced the Art Moderne and Art Deco styles. Art Moderne structures are streamlined similar to a “modern machine,” and many have rounded corners. Examples include the Greyhound bus station (ca. 1936) in Blytheville (Mississippi County) and the Studebaker Showroom (ca. 1948) in Mena (Polk County). Art Deco has been labeled the “last of the total styles.” From furniture to skyscrapers, the emphasis was on the future and materials; chrome and aluminum were frequently incorporated. Many Art Deco buildings have a vertical focus and employ geometric designs and Egyptian motifs. Structures that exhibit this form are the UARK Theater (ca. 1940) in downtown Fayetteville (Washington County), and the Medical Arts Building (ca. 1929) in Hot Springs (Garland County).

In recent decades, the Modern style has dominated. Housing styles in this mode include the ubiquitous ranch, split-level, and contemporary. An Arkansas example of Modern architecture is the Stoneflower house (ca. 1965) in Cleburne County. With flat roofs, blank walls, and an emphasis on functionality, many new government buildings fit this category.

Another style of note is folk architecture, which is built by someone who has a learned model of how finished houses, barns, bridges, or fences should look. Rather than being elaborate or decorative, these structures are conservative, functional, and traditional.

Six traditional house types can be found in the Ozarks—single pen, double pen, saddlebag, central hall cottage, dogtrot, and the I-house—and all appear in both log and frame construction. In addition to the six traditional types, there are three more nontraditional, popular types: the bent house, the prow house, and the one-story pyramid roof house. These styles are nontraditional because they do not have a log or braced frame, they are not one room (or single pile) deep, and they reflect trends in popular culture beyond Ozark architectural traditions. The Arkansas Historic Preservation Program points out that these are general classifications, and not all structures fit exactly into these categories. One of the best traditional examples is the two-story dogtrot Jacob Wolf House (ca. 1825) in Baxter County. Other notable traditional examples include the “half-dovetailed” Frierson Log Cabin (ca. 1825) in Craighead County, the double pen John Vickery Homestead in Stone County, and the Mitchell House, an 1891 central hall cottage in Yell County.

Another example of vernacular architecture in Arkansas is the shotgun house, found throughout the Delta. A shotgun house is so named because when looking through the entrance, a person can see through the back exit, thereby making it possible to fire a shotgun down the house’s entire length, usually three rooms deep. Such houses are often found with their gable side rather than their long side facing the road.

More contemporary folk architecture is also found in abundance. This includes mobile homes, Quonset huts, A-frames, and geodesic domes. Of this list, mobile homes are the most common. The 2000 Census indicated that Arkansas had 1,173,043 housing units, 14.9 percent of which were mobile homes. Additionally, several roadside eateries are housed in contemporary A-frame buildings, and the Burdette school gym (ca. 1948) in Mississippi County is a Quonset hut, which also demonstrates modern architecture’s focus on utility and function, not necessarily the quality and/or form.

Bridges, barns, granaries, and other utility structures should not be overlooked. Many of Arkansas’s older structures need renovation and preservation, especially historic bridges, which are falling victim to the ravages of time and were not built to handle today’s automobile and truck traffic loads. Examples include the concrete Fourche LaFave Bridge (ca. 1941) in Perry County, the Little Missouri River Bridge (ca. 1910) in Clark County, and the stone Cedar Creek Bridge in Petit Jean State Park in Conway County (ca. 1934).

For additional information:

Burns, Richard Allen. “The Shotgun Houses of Trumann, Arkansas.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 33 (April 2002): 44–51.

Dunnahoo, Patrick. Dog Trots and Drawing Rooms: How Arkansans Lived in the Years Between the Two World Wars. Benton, AR: Patrick Dunnahoo, 1989.

Harington, Donald. The Architecture of the Arkansas Ozarks. New Milford, CT: Toby Press, 2004.

McLaren, Christie. Arkansas Highway History and Architecture, 1910–1965. Little Rock: Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, 1999.

Nichols, Cheryl, and Helen Barry. The Arkansas Designs of E. Fay Jones, 1956–1997. Little Rock: Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, 1999.

Sizemore, Jean. Ozark Vernacular Houses: A Study of Rural Homeplaces in the Arkansas Ozarks, 1830–1930. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994.

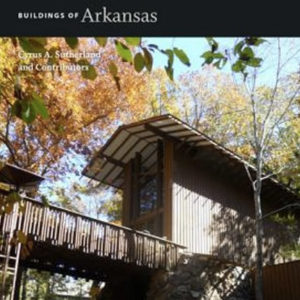

Sutherland, Cyrus A., et al. Buildings of Arkansas. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2018.

Winningham, Geoff. Of the Soil: Photographs of Vernacular Architecture and Stories of Changing Times in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2014.

Jason Combs

Arkansas State University

Arts, Culture, and Entertainment

Arts, Culture, and Entertainment Coolidge House

Coolidge House Frederick Hanger House

Frederick Hanger House Garrott House

Garrott House Historic Preservation

Historic Preservation Lakeport Plantation

Lakeport Plantation McCollum-Chidester House Museum

McCollum-Chidester House Museum Ozark Vernacular Architecture

Ozark Vernacular Architecture Art Moderne Bus Station

Art Moderne Bus Station  Berger-Graham House

Berger-Graham House  Buildings of Arkansas

Buildings of Arkansas  Casey House

Casey House  Clinton Presidential Library and Museum

Clinton Presidential Library and Museum  Ed W. Dozier House

Ed W. Dozier House  Estevan Hall

Estevan Hall  Frierson Log Cabin

Frierson Log Cabin  Greathouse Home

Greathouse Home  Hempstead County Courthouse

Hempstead County Courthouse  Jackson County Courthouse

Jackson County Courthouse  Jacob Wolf House

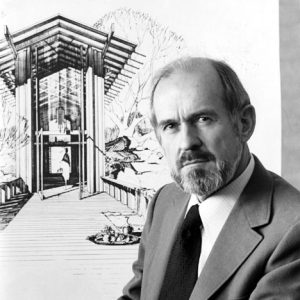

Jacob Wolf House  Fay Jones

Fay Jones  Leake-Ingham Library

Leake-Ingham Library  Magnolia Antebellum House

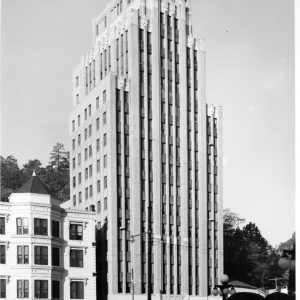

Magnolia Antebellum House  Medical Arts Building

Medical Arts Building  Pillow-Thompson House

Pillow-Thompson House  Trinity Episcopal Church

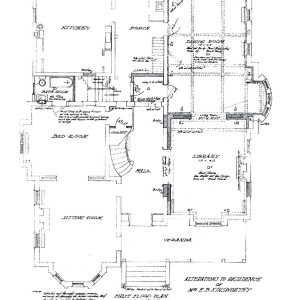

Trinity Episcopal Church  Villa Marre First Floor

Villa Marre First Floor

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.